The Legendary Charlie Chaplin

Frequently controversy erupts on social media over artists who directly copy other artists’ work. The issue of exactly where the dividing line lies between "homage" and "ripoff" is open for debate among fans, but today I want to speak to the artists out there… and in particular, aspiring animators. For you, this subject is more than just idle chatter.

Every day, an artist makes thousands of decisions. These decisions affect not just the piece he is working on at the time, but his entire creative output. It’s important to understand why you’re making the decisions you make, and to strive to work your problems out for yourself; not just apply someone else’s decisions as a substitute for your own. Truly great artists refuse to even copy themselves… Take Terry-Toons animator Jim Tyer for instance. He never approached the same situation with the same animation twice in his entire career.

There are consequences to the decisions we make as artists. Sometimes in the heat of creativity, right and wrong can become blurred by practicality and commercial demands. It’s up to you to balance those competing pressures, but as the old saying goes, "Virtue is its own reward."

It’s hard to not react with bias to current examples of imitation, but time can lend clarity. I’m going to tell you about two performers who were popular nearly a century ago. One of them you know. The other you don’t. The reason for that is in the decisions those two artists made. -Stephen Worth

Edgar Kennedy and Charlie Chaplin

In 1916, Charlie Chaplin signed a contract with Mutual to produce 12 comedy shorts over a year and half’s time. He was paid the unheard of amount of $670,000 for the shorts, and was given unprecidented creative freedom. We now know that the end result of this deal was a package of slapstick shorts that represent the most influential comedy films in the entire history of cinema. But back in 1916, it was just a LOT of money being paid to a relatively untested artist.

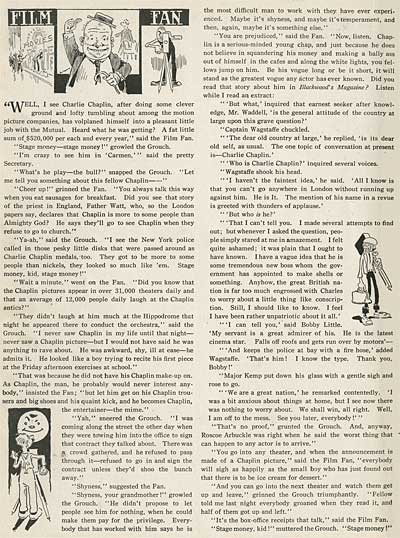

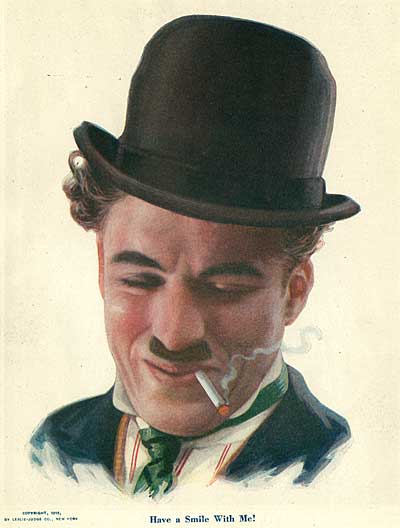

Here is an anthology that pulled together articles from Judge magazine during this seminal period in movie history…

In the pages of this anthology is this article on Chaplin’s deal with Mutual. Although the form of the prose is quite different from what we read today in entertainment magazines and blogs, the apologies for appealing to the unrefined masses, complaints about big budgets, and stories about movie-star ego trips are the same sorts of sniping we read in reviews today. What this writer didn’t know was that Chaplin was on the cusp of breaking through as the single most important filmmaker of his time.

Now that the stage is set, I want to introduce you to "The Shadow"…

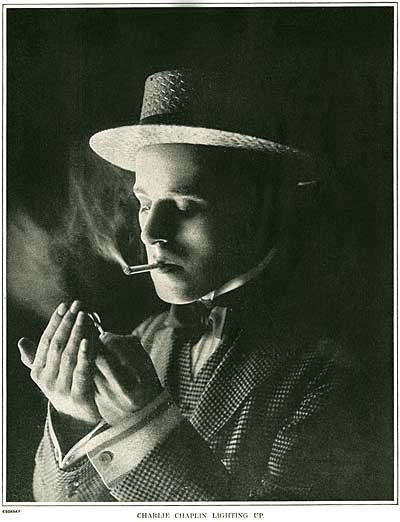

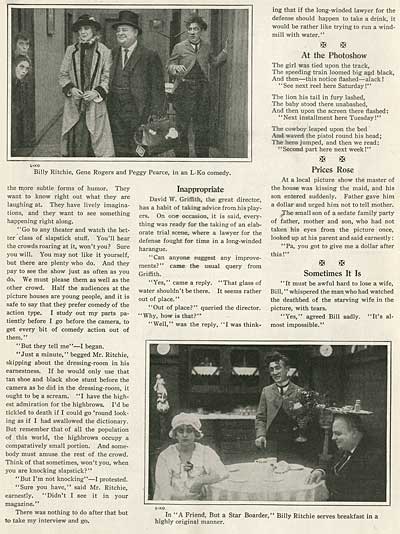

![]() Billy Ritchie told reporters that he had worked alongside Chaplin on stage, and claimed that he had performed as the drunk in the classic sketch, "Mumming Birds", just as Chaplin had done in his English Music Hall days. Chaplin’s biographer, David Robinson described the “mumming Birds” sketch like this…

Billy Ritchie told reporters that he had worked alongside Chaplin on stage, and claimed that he had performed as the drunk in the classic sketch, "Mumming Birds", just as Chaplin had done in his English Music Hall days. Chaplin’s biographer, David Robinson described the “mumming Birds” sketch like this…

The setting for "Mumming Birds" represents the stage of a small music hall, with two boxes at either side. The sketch opens with fortissimo music as a girl shows an elderly gentleman and his nephew- an objectionable boy, armed with peashooter, tin trumpet, and picnic hamper- into the lower O.P. box.

The Inebriated Swell is settled into the prompt side box, and instantly embarks upon some business of a very Chaplinesque character. He peels the glove from his right hand, tips the waiting attendant, and then, forgetting that he has already removed his glove, absently attempts to peel it off again. He tries to light his cigar from the electric light beside the box. The boy holds out a match for him, and in gracefully inclining to reach it, the Swell falls out of the box.

![]() The show within the show consisted of a series of abysmal acts… The acts changed over the years, but some remained invariable: a ballad singer, a male voice quartet, and the Saucy Soubrette, delighting the Swell with her rendering of "You Naughty, Naughty Man!"

The show within the show consisted of a series of abysmal acts… The acts changed over the years, but some remained invariable: a ballad singer, a male voice quartet, and the Saucy Soubrette, delighting the Swell with her rendering of "You Naughty, Naughty Man!"

The finale was always "Marconi Ali, the Terrible Turk- the Greatest Wrestler Ever to Appear Before the British Public". The Terrible Turk was a poor, puny little man weighed down by an enormous mustache, who would leap so voraciously upon a bun thrown at him by the Boy that the Stage Manager had to cry out, "Back, Ali! Back!" The Turk’s offer to fight any challenger for a purse of £100 provided the excuse for a general scrimmage to climax the act.

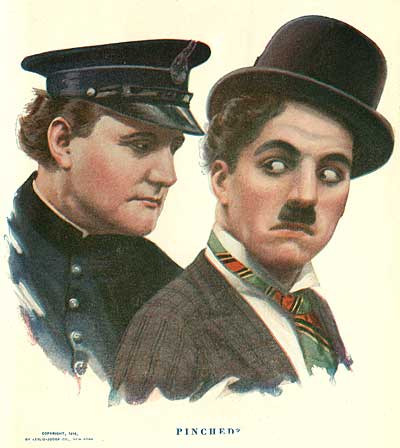

Ritchie was a British comic like Chaplin, so when Chaplin began to rise to fame, he was a natural choice to put out film comedy shorts to compete. Henry Lehrman, who was previously a director at Mack Sennett, hired Ritchie to star in a series under his "Lehrman Knock-Outs" banner. The comparisons with Chaplin were inevitable. Ritchie used the same costume that Chaplin wore… the bowler hat, bamboo cane and tattered suit that became famous as the Little Tramp costume.

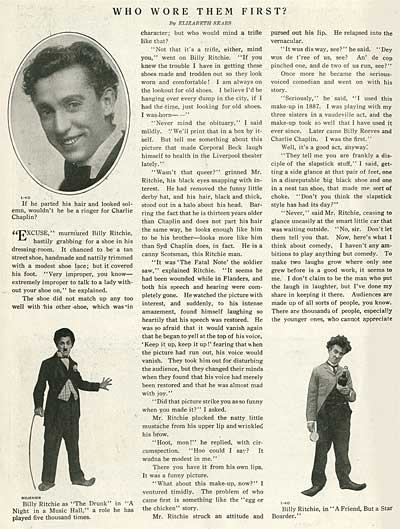

Here is an interview with Ritchie made around 1916 where he claims to have created the Little Tramp costume before Chaplin used it…

The author of this article makes it clear that Ritchie’s career has one foot planted in his own shoes, and the other in Chaplin’s. But there is more to the story of Billy Ritchie that that… The truth was, it was all a lie. Ritchie had never worked with Chaplin on the Music Hall stage. He didn’t perform the drunk in “Mumming Birds”. And the Little Tramp costume didn’t come from his own vaudeville act. Ritchie had stolen Chaplin’s costume, his act, and his resume. He hoped to parlay this deception into stealing his audience as well.

But it didn’t last… When Chaplin’s Mutual Shorts were released, they were a sensation. They blew Ritchie out of the water. Lehrman was forced to change distributors to Universal in 1917, and the quality of the films took a nose dive. Two years later, Ritchie was attacked on the set by an ostrich, and never recovered. He died from the injuries he sustained in 1921, leaving his wife without financial support.

Chaplin imitator, Billy West

Billy Ritchie wasn’t the only Chaplin imitator… Billy West and Charles Amador also traded on the image of the Little Tramp; and a cartoon series produced by Gaumont in Europe exploited the character as well. Chaplin sued to protect his creation, but ultimately his own success and brilliant creativity plowed his imitators under better than any legal writ.

For some reason, Chaplin never sued Billy Ritchie, but after Ritchie’s death, he took pity on his widow and gave her a job as his costumer. She prepared the Little Tramp costume for Chaplin’s performances, just as she had for her late husband.

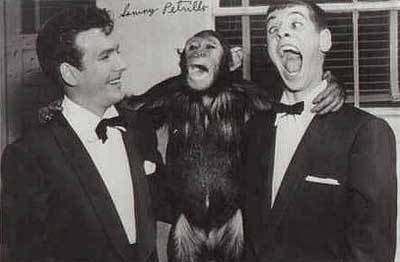

The history of film is full of stories like this. Here are Duke Mitchell and Sammy Petrillo…

…remember them? No? Well, that’s because they didn’t last either. Petrillo was quoted as saying, "I hold the record for being the world’s youngest has-been."

In time, surface similarities like the hat and cane ceased to matter. Audiences didn’t love Chaplin for his costume. It was the spark of genius in the creator that made the Little Tramp immortal. You can’t steal genius. You may gain a short term benefit from ripping off another artist to further your own career, but you’ll pay for it in the end.

The moral of this cautionary tale is to be true to yourself. The business has no shame. The audience won’t sue you for ripping off someone else’s idea. You need to develop a conscience for yourself. No one is going to do it for you. You owe it to your muse.

If you want an incredible insight into the mind of a brilliant filmmaker, you will want to get the DVD of Unknown Chaplin. Using never before seen outtakes, these three programs reconstruct Chaplin’s creative process from the ground up. This is one of the greatest documentaries ever made. Check it out!

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit entitled Theory.