Disney Studios

If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably daydreamed about going back in time to be a "fly on the wall" at a golden age cartoon studio. Imagine getting the chance to witness how your favorite cartoons were written and see the twists and turns they took from initial idea to finished story. Unfortunately, that isn’t likely to happen. But we can find out an awful lot about the process used to write classic cartoons by looking at the scraps of paper left behind by the great artists who wrote them. I’m going to do just that in a series of posts over the next few weeks.

The specifics of the process of writing cartoons in the classic era varied a bit from studio to studio and from time period to time period. Like every other part of the production line, there was an evolution as experimentation led to the development of more effective techniques. But the general outline of the progress of a story from raw idea to boards ready to put into production didn’t vary all that much. I’m going to show you some specific examples that illustrate these general concepts in the hopes that you might come away with a better understanding of how cartoons were created.

Warner Bros.

THE GAG SESSION

The idea for a cartoon would start with a simple premise- a few sentences that described the general theme of the cartoon. For example… "Porky is a bullfighter." or "Mickey, Donald and Goofy are ghost exterminators." In the premise there would be no real attempt at describing details of the plot, just a simple statement of a situation or series of situations that might offer entertaining possibilities.

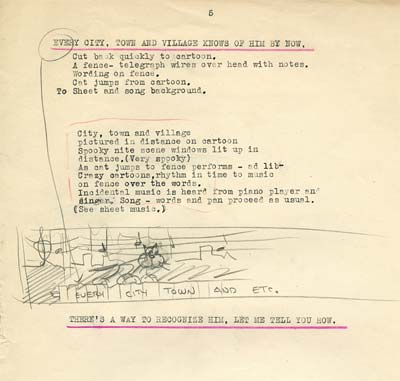

Premise for a 1930s Barney Google/Snuffy Smith cartoon.

Once the premise was chosen, a group of artists would be called together for an initial gag session to come up with ideas. At Warner Bros, this meeting was referred to as a "No No Session", which meant that no one was allowed to say "no" to any idea- all suggestions were fair game. At this stage, the gags were generally isolated variations on the basic theme of the premise, with no attempt to put them into any sort of continuity or plot. The goal was to come up with funny situations that could be expanded upon and reworked into something more specific further down the line.

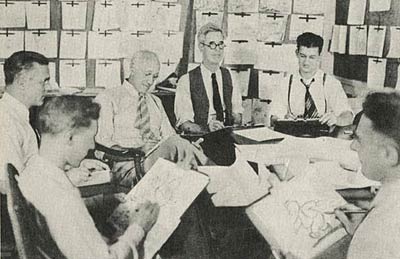

Terry-Toons

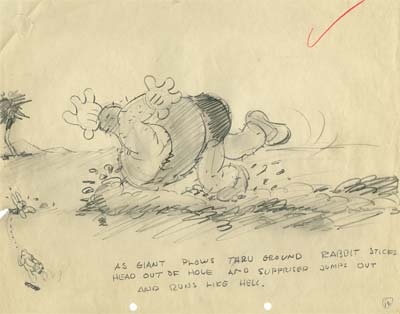

The artists would sit with pads and pencils or lap boards, jotting down notes and doodling up thumbnail sketches of what the ideas might look like. The sketches might be pinned up on a cork board so the other artists could work gags off if it. One person would be responsible for taking notes for the group, so after the meeting was over, the story man could go back and refresh his memory of a specific gag. As the doodles and notes piled up, certain themes would form, gags would lead to follow up gags and build to "topper gags". A continuity would begin to take shape.

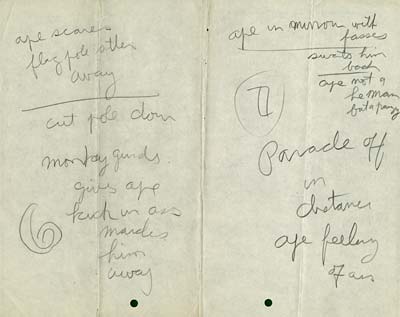

The notes taken at early story meetings were usually for the artists’ own reference, so the sketches were loose and the notes were scribbled down quickly. This makes them quite difficult for the layman to read. A certain amount of deciphering is required. At the bottom of each example, I summarize the contents of the notes. You might want to print them out. It’s easier to study them in a hard copy than on the computer screen.

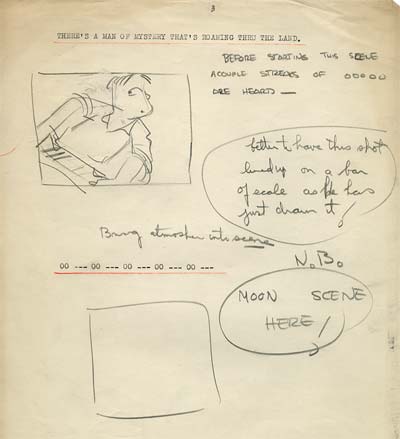

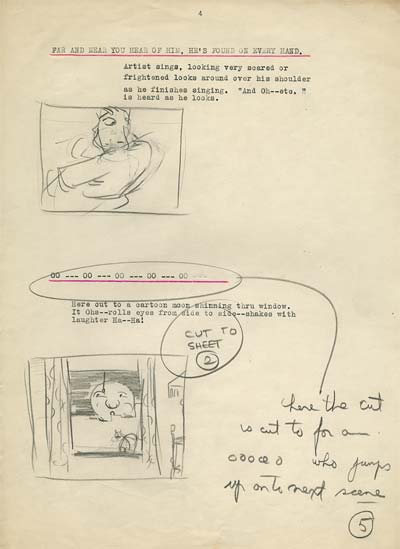

Here are story notes from an unmade Fleischer Screen Song cartoon from the late 1920s. Based on the song, "Mysterious Mose", this premise was shelved and revived a couple of years later as a Betty Boop cartoon.

It appears that a little bit of development had occurred by the time this document was created, but not much. The lyrics are typed out with lots of space for drawing out the action between each line. The character of the piano player is to be in live action, while the moon and the cat are animated. The first page refers to the location of the beginning of the song on the bar sheet and indicates that a scene of the moon on the second page should be moved forward to this page, to allow the cat to be the focus of the shot the second time up.

The notes say that the second shot on this page should be focused on the cat, and he should jump from this scene cut to the next scene for the bouncing ball sequence.

Here we have all the lyrics of the song, and a quick outline of the sorts of gags the artists should come up with for the bouncing ball section of the film. By the end of the meeting, the director would have a stack of gag drawings to choose from. In the early days of animation, the story process was very informal, and the individual animator was often expected to flesh out the specifics of the action in his scenes on his own, co-ordinating with the animator of the preceding and following sequence on the hookup between sequences. Dave Fleischer was known to add gags all the way up to the animation stage.

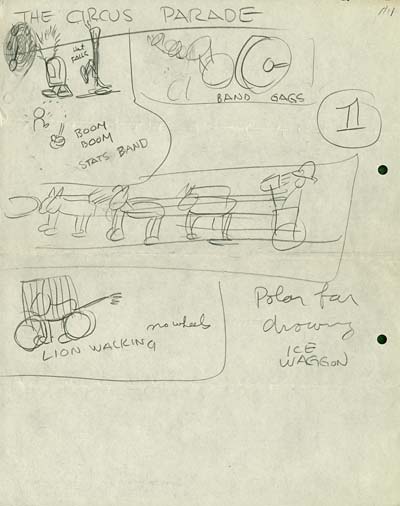

There aren’t a lot of doodles on this next document, which dates back to the Charles Mintz Studio around 1934. Some gags are indicated by just a few terse words. This probably means that these notes were accompanied a pile of drawings, which the story man was trying to order into a basic continuity. The action has been divided into seven segments, each one representing approximately a minute of screen time.

The First Segment shows a circus parade arriving in town. A drum major disappears into his oversized hat; a french horn player pops out of a tuba to take a solo; a team of horses pans through pulling a street sweeper behind, a lion cage is propelled by the lion’s own legs- no wheels; and a polar bear drowns in an ice wagon full of melted ice.

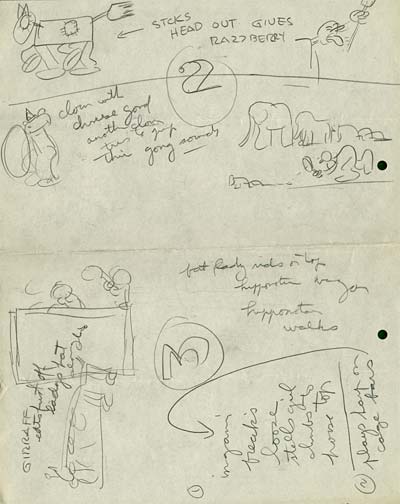

In the Second Section the parade continues. A clown in a horse costume sticks his head out the tail and gives the crowd a razzberry; a clown jumps through a paper hoop- but it’s actually a Chinese gong; a parade of elephants- each one smaller than the one before- ends with an elephant so tiny, a clown has to use a magnifying glass to see it.

The Third Section includes a giraffe whose neck extends to eat the fake fruit off the hat of a lady in the crowd; a fat lady riding a hippopotamus wagon, and a gorilla who plays the harp on his cage bars, then escapes and kidnaps a girl. He snatches her up to the house tops.

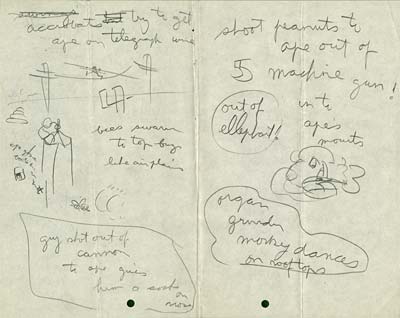

Part Four: The circus performers attempt to rescue the girl. A tightrope walker walks on telegraph lines to reach the ape; a man is shot out of a cannon and the ape socks him in the nose; the ape perches on the top of a building and bees buzz around him like the airplanes buzzing King Kong.

In Part Five, an elephant shoots peanuts at the ape like a machine gun as an organ grinder’s monkey dances on the rooftops.

Part Six: The ape scares a flagpole sitter away from his perch and replaces him on the top of the pole. The organ grinder monkey cuts down the pole, gives the ape a big kick in the ass and marches him away.

Part Seven: The ape sees his reflection in a mirror and makes faces. The reflection swats him. The ape, who we expect to act like a he-man, acts like a pansy instead. The parade marches off into the distance as the ape rubs his sore ass from where the monkey kicked him.

In the next installment of this series on Cartoon Writing, I will show you a batch of sketches that document a story session at the Iwerks Studio in 1934.

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of an online series of articles dealing with Instruction.