REFPACK 015

March-April 2017

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Every other month, members of Animation Resources are given access to an exclusive Members Only Reference Pack. These downloadable files are high resolution e-books on a variety of educational subjects and rare cartoons from the collection of Animation Resources in DVD quality. Our current Reference Pack has just been released. If you are a member, click through the link to access the MEMBERS ONLY DOWNLOAD PAGE. If you aren’t a member yet, please JOIN ANIMATION RESOURCES. It’s well worth it.

PDF E-BOOK:

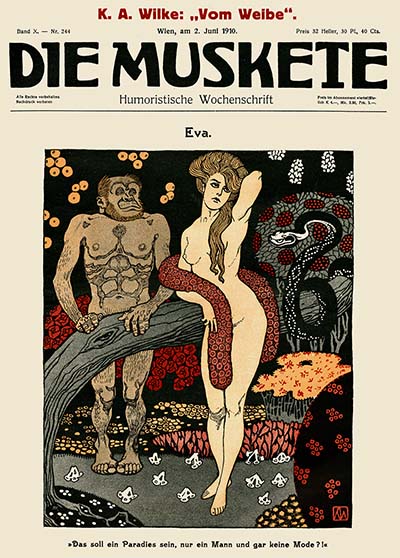

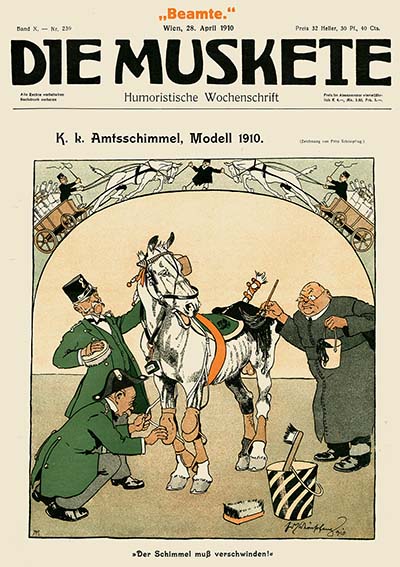

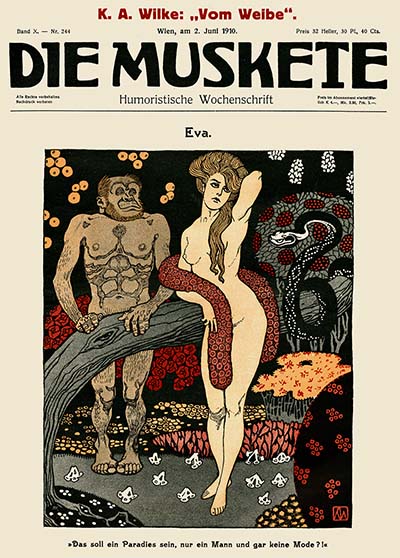

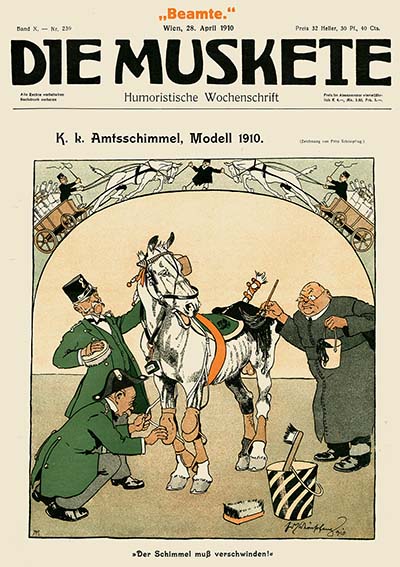

Die Muskete

Volume 10 Nos. 236-252 (April-July 1910)

During the 19th century, society had a totally different relationship with cartoons than we do today. Beginning with artists like James Gillray and George Cruickshank in early decades of the century, cartoons were seen as serious business. They crystalized the image of the rich and powerful in the minds of the masses, and even Kings and religious leaders were forced to take notice of their impact. The pen truly had become “mightier than the sword”.

During the 19th century, society had a totally different relationship with cartoons than we do today. Beginning with artists like James Gillray and George Cruickshank in early decades of the century, cartoons were seen as serious business. They crystalized the image of the rich and powerful in the minds of the masses, and even Kings and religious leaders were forced to take notice of their impact. The pen truly had become “mightier than the sword”.

With the dawn of the 20th century, the lives of people were changing. The modern world was emerging, and with it came pressures brought on by technology, new forms of government, colonialism and war. The gloves were off– cartoonists no longer limited their satire to Kings and religious leaders. They wielded their power to satirize by skewering everyone and everything around them– religion, ethnicity, the rich as well as the poor, and the power that the government held over the public. Cartooning became a powerful tool for changing hearts and minds, as well as disseminating nationalistic propaganda. The conflicts that these new challenges created began building to a head, and it would eventually result in “The Great War”, World War I.

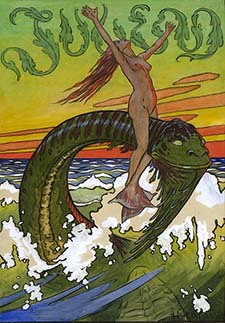

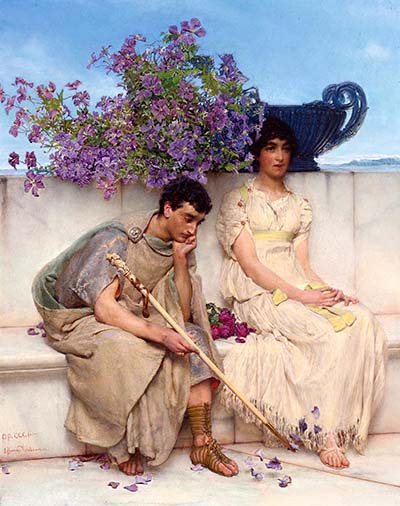

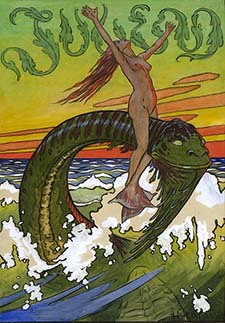

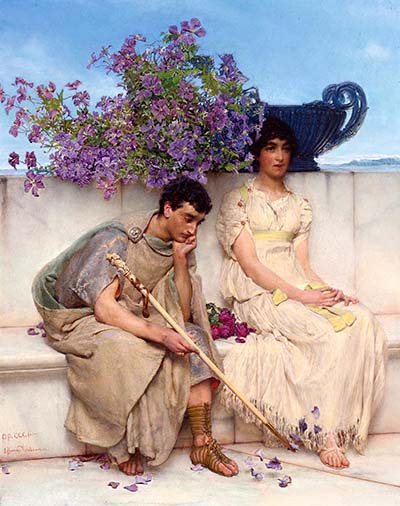

But even though it was a difficult time politically, the world was experiencing a renaissance in the arts. There were two principle styles during this period: Historicism and Art Nouveau. Historicism was an ecclectic style which embraced neo-classical forms and themes. The subject matter consisted of idealized imagery of ancient Greece, mythological and historical tableaux, or exotic locales in faraway lands. The other popular style was Art Nouveau. In Germany, it was known as Jugendstyl (Jugend Style), named after Jugend, one of the most famous arts magazines of the day. Art Nouveau was based on craftsmanship and hand work. It rebelled against the machine-made look that was taking hold in graphics and consumer products in the early industrial age. It did this by putting the hand of the artist at the forefront and incorporating lush organic patterns derived from nature. These two styles were represented in all forms of art, from architecture to interior design, to ceramics, fabrics, fashion, sculpture, illustration… and even cartooning.

But even though it was a difficult time politically, the world was experiencing a renaissance in the arts. There were two principle styles during this period: Historicism and Art Nouveau. Historicism was an ecclectic style which embraced neo-classical forms and themes. The subject matter consisted of idealized imagery of ancient Greece, mythological and historical tableaux, or exotic locales in faraway lands. The other popular style was Art Nouveau. In Germany, it was known as Jugendstyl (Jugend Style), named after Jugend, one of the most famous arts magazines of the day. Art Nouveau was based on craftsmanship and hand work. It rebelled against the machine-made look that was taking hold in graphics and consumer products in the early industrial age. It did this by putting the hand of the artist at the forefront and incorporating lush organic patterns derived from nature. These two styles were represented in all forms of art, from architecture to interior design, to ceramics, fabrics, fashion, sculpture, illustration… and even cartooning.

An example of Historicism by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Technology wasn’t altogether as bad a thing for the arts as the Art Nouveau movement believed though. Lithography in the 19th century was beginning to enable the mass production of high quality images, exploiting new printing techniques to produce art magazines and satirical caricature journals. The oldest of these caricature magazines was the French weekly, La Charivari, which began publication in 1832. The title referred to a folk custom where peasants would perform a mocking, off pitch serenade accompanied by a cacophony of banging on pots and pans to shame adulterers, cuckolds, widows who planned to remarry before the proper period of mourning had passed, or to encourage reluctant sweethearts to marry. It was an apt reference, because La Charivari was host to a cacophony of highly critical satirical articles chastising the moral standards of the time, as well as scathing caricatures of famous people.

Technology wasn’t altogether as bad a thing for the arts as the Art Nouveau movement believed though. Lithography in the 19th century was beginning to enable the mass production of high quality images, exploiting new printing techniques to produce art magazines and satirical caricature journals. The oldest of these caricature magazines was the French weekly, La Charivari, which began publication in 1832. The title referred to a folk custom where peasants would perform a mocking, off pitch serenade accompanied by a cacophony of banging on pots and pans to shame adulterers, cuckolds, widows who planned to remarry before the proper period of mourning had passed, or to encourage reluctant sweethearts to marry. It was an apt reference, because La Charivari was host to a cacophony of highly critical satirical articles chastising the moral standards of the time, as well as scathing caricatures of famous people.

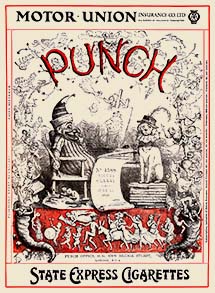

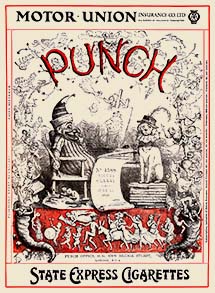

In less than a decade, La Charivari had made so much of an impact that similar publications started springing up all over Europe. In 1841, the British publication, Punch: The London Charivari was established. Before this time, the word “cartoon” had a different meaning– it was only used to describe a preliminary sketch for a painting. But in 1843 there was an exhibit of “cartoons” for proposed murals in the House of Parliament, and Punch suggested that its satirical drawings would make even better murals in the lawmaker’s halls. The term “cartoon” was applied to the humorous drawings in Punch, and the term has stuck ever since.

In less than a decade, La Charivari had made so much of an impact that similar publications started springing up all over Europe. In 1841, the British publication, Punch: The London Charivari was established. Before this time, the word “cartoon” had a different meaning– it was only used to describe a preliminary sketch for a painting. But in 1843 there was an exhibit of “cartoons” for proposed murals in the House of Parliament, and Punch suggested that its satirical drawings would make even better murals in the lawmaker’s halls. The term “cartoon” was applied to the humorous drawings in Punch, and the term has stuck ever since.

Over the next few decades, satirical magazines flourished all over the world. La Rire (The Laugh) and L’Assiette au Beurre (Man & Beast) began publication in France in 1894 and 1901 respectively. Italy had several humorous journals in addition to La Charivari, most notably Il Lampioni (The Street Fights). In Germany, Fliegende Blatter (Flying Leaves) was founded in 1845 along similar lines to Punch, and Kladderasdatsch (Scandal) followed two years later. The art of caricature spread as far as Argentina with the magazine Caras y Caretas (Faces & Masks) in 1898.

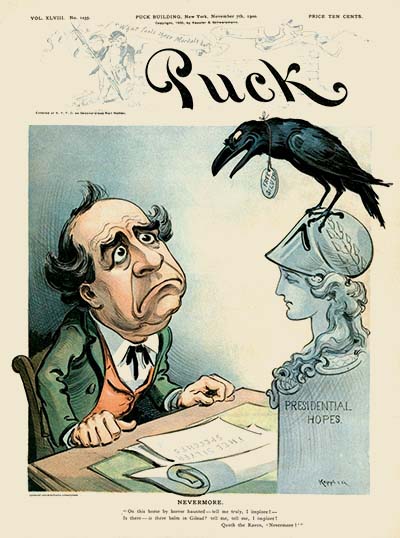

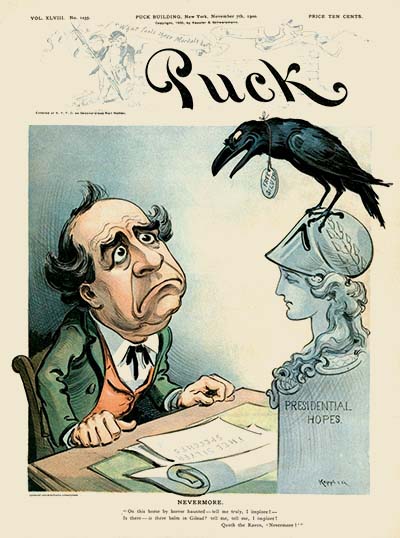

Meanwhile in America, cartoonist Thomas Nast was exerting great power, lampooning the corruption of the Tammany Hall politicians in the pages of Harper’s Weekly. The “New World” was ready for some “Old World” satire, so in 1871, German immigrant Joseph Keppler founded Puck magazine in the image of Punch. A decade later, some of the key artists at Puck defected from the publication to establish Judge as a conservative alternative to the more liberal Puck. (For more information, see the third volume of our e-book series on Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman’s cartooning course).

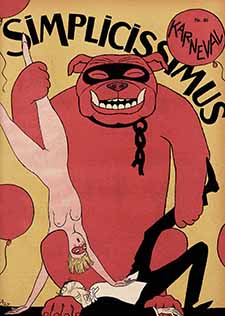

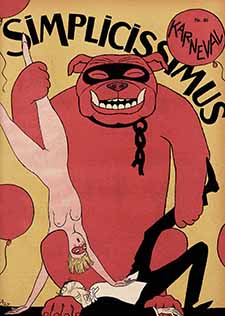

But arguably, the greatest of all of the satirical caricature magazines came from Munich, Germany. While Jugend (Youth) magazine provided a more respectable image based on Art Nouveau, the opposite extreme was represented by Simplicissimus (Simpleton). Simplicissimus was the most audacious and daring magazine of the day, lampooning the stiffness of officers of the military, class divisions, loose social morals and inevitably, powerful political leaders. Its reckless determination to offend destined it for trouble, and it didn’t take long.

But arguably, the greatest of all of the satirical caricature magazines came from Munich, Germany. While Jugend (Youth) magazine provided a more respectable image based on Art Nouveau, the opposite extreme was represented by Simplicissimus (Simpleton). Simplicissimus was the most audacious and daring magazine of the day, lampooning the stiffness of officers of the military, class divisions, loose social morals and inevitably, powerful political leaders. Its reckless determination to offend destined it for trouble, and it didn’t take long.

In 1898 Kaiser Wilhelm objected to a caricature of himself on the cover of Simplicissimus. He shut down the magazine, forced its publisher to flee to Switzerland, and threw the cartoonist, Theodor Heine in jail. Like a phoenix, Simplicissimus soon sprang up again, but it continued to have legal troubles with the government and religious leaders until the Nazis came to power in the mid-1930s. The Nazis despised everything that the magazine stood for, but they didn’t shut Simplicissimus down. They purged it of the Jewish employees and weeded the ranks of its most radical writers and artists. They succeeded in blunting its impact considerably, a blow from which the magazine never recovered. Simplicissimus ceased publication at the end of World War II, and was re-established for a while in the mid-1950s, but by that time it was pale shadow of its former self.

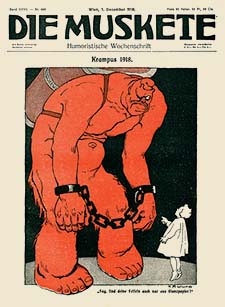

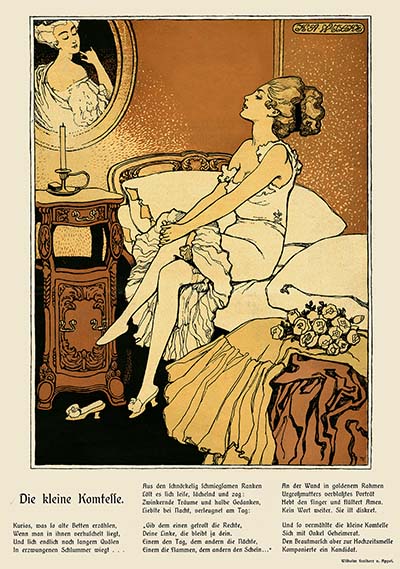

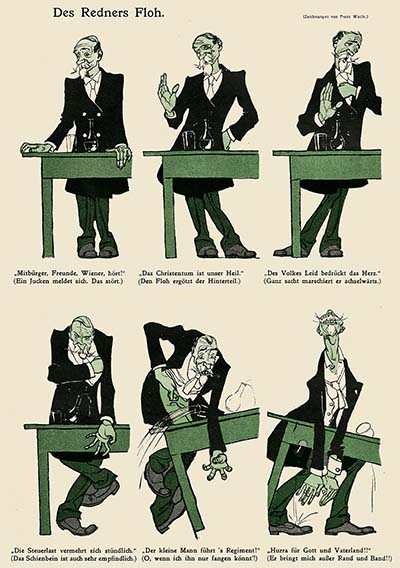

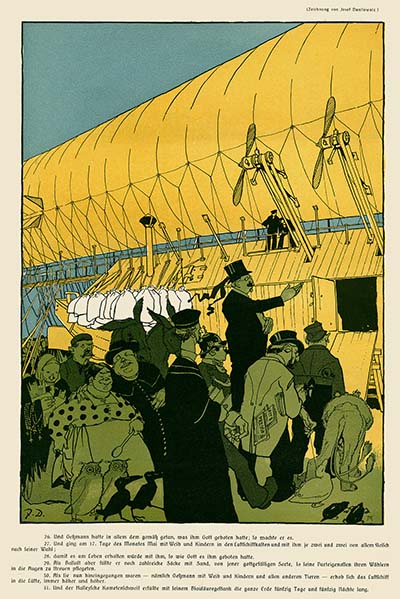

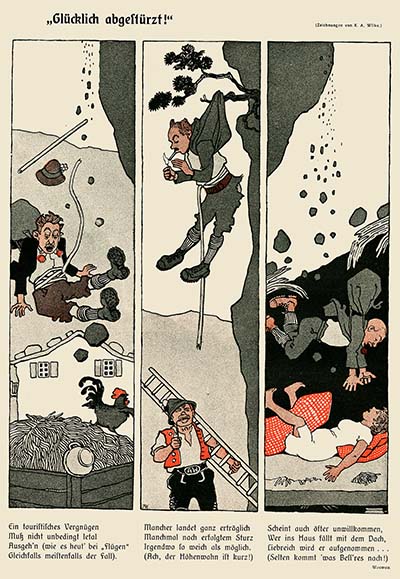

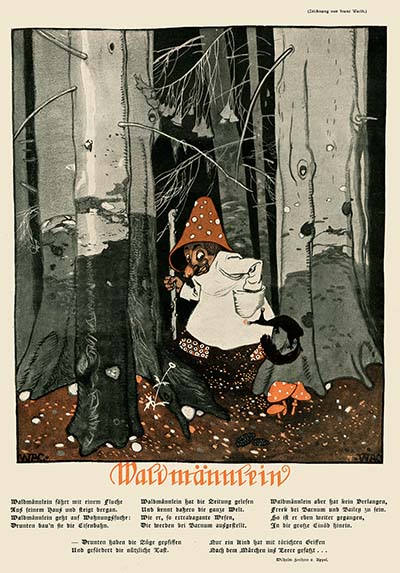

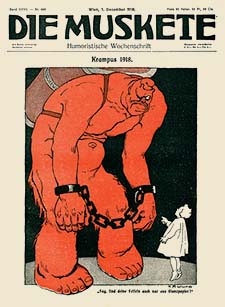

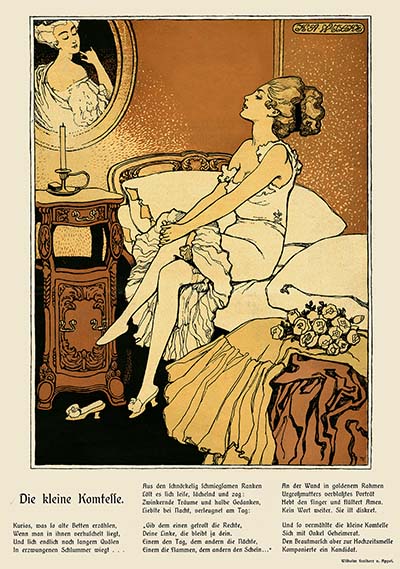

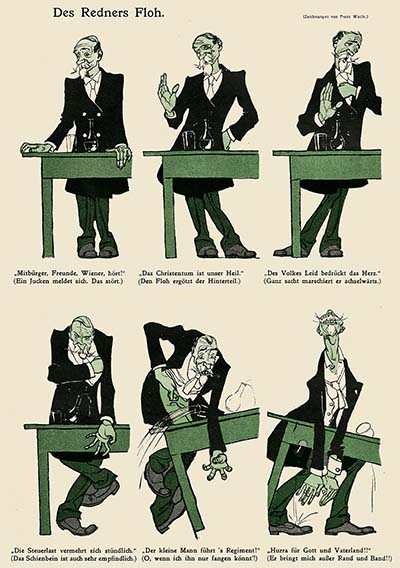

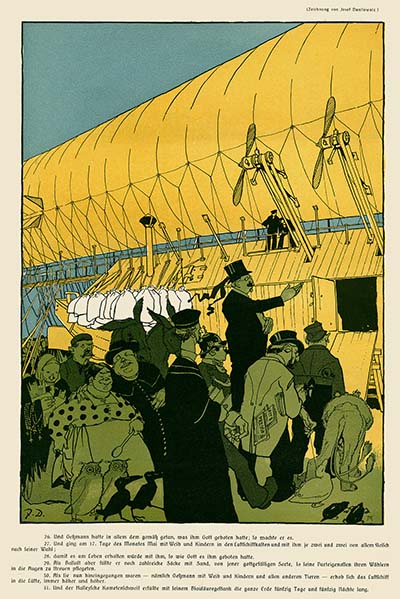

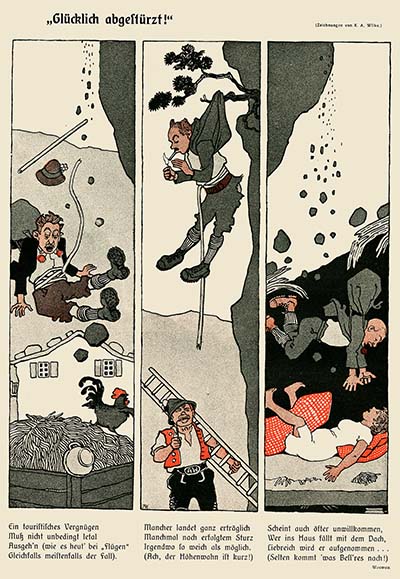

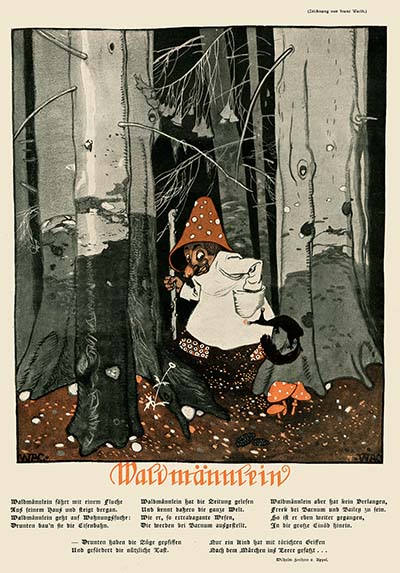

The center of the arts in this region was Vienna, Austria, so it is natural that a great caricature magazine would come from that city– Die Muskete (The Rifle). The principles behind Die Muskete were initially quite different than either Jugend or Simplicissimus. It was a humorous “men’s magazine” aimed at military officers and veterans. It still made fun of bureaucratic excesses, military inefficiency, social mores, the battle of the sexes, and religion, as well as political corruption, while remaining steadfastly loyal to the Emperor of Austria. The staff consisted entirely of local artists like Fritz Schönpflug, Karl Wilke and Franz Wacik. Each one brought something different to the table. Schönpflug specialized in military caricature, gently poking fun at the men who made up a large part of Die Muskete’s subscriber base, Wilke excelled at drawing pretty girls with a nouveau flair. And Wacik specialized in a wide range of fantastic subjects- strange creatures and fairy tale settings. Working along side them were the political cartoonist Josef Danilowatz, fashion artist Heinrich Krenes, and the brilliant caricaturist Carl Josef. These artists were well matched as a team to provide a variety of images and approaches. During World War I the focus of Die Muskete shifted from being a humor magazine to being a magazine for soldiers in the trenches. The tone became more political and the focus shifted to demonizing the enemy. But the level of artistry remained at a high level until many of the original team of artists began to leave the magazine in the mid 1920s.

The center of the arts in this region was Vienna, Austria, so it is natural that a great caricature magazine would come from that city– Die Muskete (The Rifle). The principles behind Die Muskete were initially quite different than either Jugend or Simplicissimus. It was a humorous “men’s magazine” aimed at military officers and veterans. It still made fun of bureaucratic excesses, military inefficiency, social mores, the battle of the sexes, and religion, as well as political corruption, while remaining steadfastly loyal to the Emperor of Austria. The staff consisted entirely of local artists like Fritz Schönpflug, Karl Wilke and Franz Wacik. Each one brought something different to the table. Schönpflug specialized in military caricature, gently poking fun at the men who made up a large part of Die Muskete’s subscriber base, Wilke excelled at drawing pretty girls with a nouveau flair. And Wacik specialized in a wide range of fantastic subjects- strange creatures and fairy tale settings. Working along side them were the political cartoonist Josef Danilowatz, fashion artist Heinrich Krenes, and the brilliant caricaturist Carl Josef. These artists were well matched as a team to provide a variety of images and approaches. During World War I the focus of Die Muskete shifted from being a humor magazine to being a magazine for soldiers in the trenches. The tone became more political and the focus shifted to demonizing the enemy. But the level of artistry remained at a high level until many of the original team of artists began to leave the magazine in the mid 1920s.

It’s important to remember that in the heyday of caricature journals, the artists didn’t identify strictly as cartoonists. For instance Franz Wacik was a designer for the theater, he painted frescos and murals, and he illustrated children’s books. Most of the cartoonists at Die Muskete were ne artists as well as being cartoonists, and this is typical of of their contemporaries at other caricature journals. There’s a lot to learn from these talented artists. I hope you find this e-book useful.

This e-book file is set up for printing on 8 1/2 by 11 three hole punch paper, and is optimized for high quality display on tablets and high resolution computer monitors. Thanks to JoJo Baptista for sharing his collection of these rare magazines with us.

REFPACK015: Die Muskete Vol. X

Adobe PDF File / 299 Pages / 943 MB Download

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Not A Member Yet? Want A Free Sample?

Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

by

by

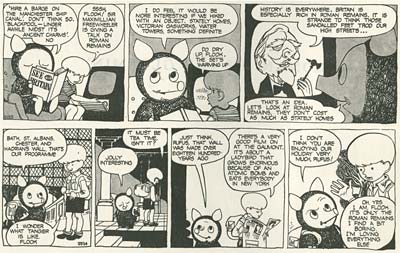

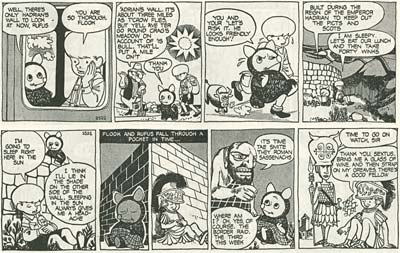

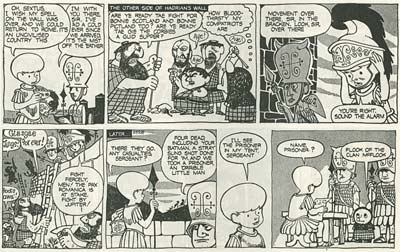

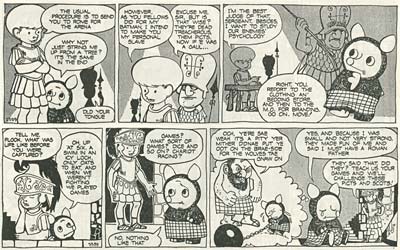

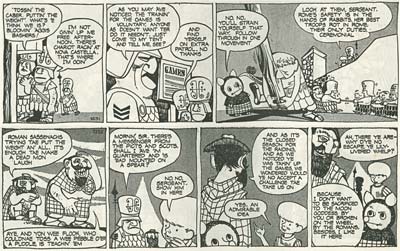

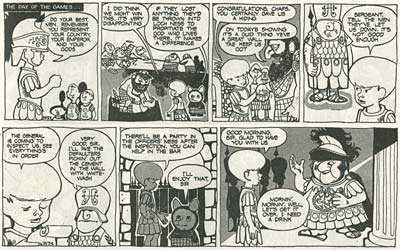

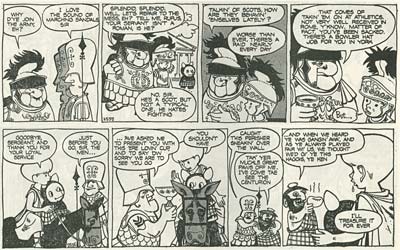

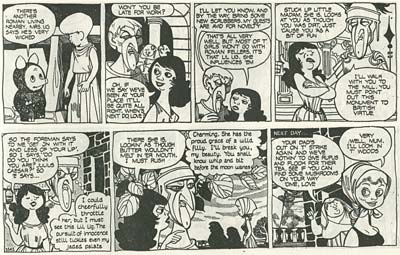

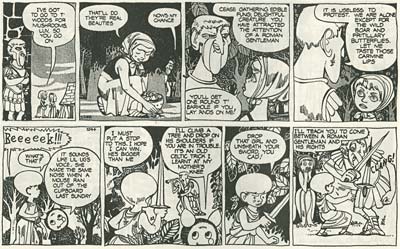

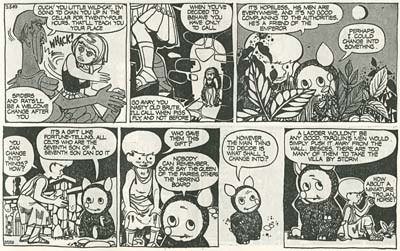

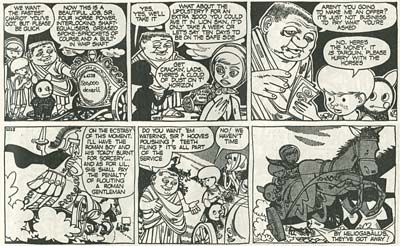

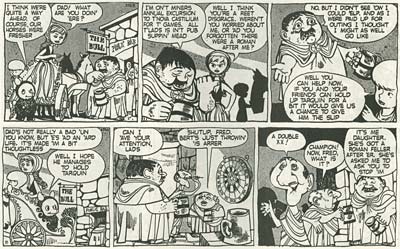

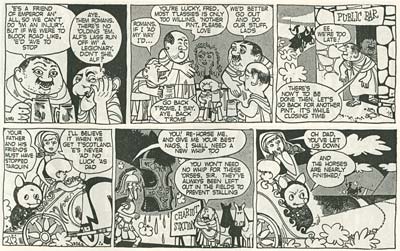

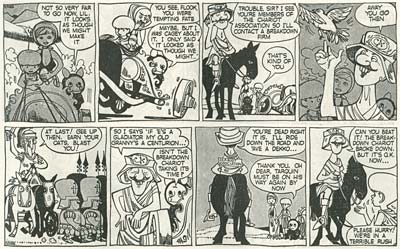

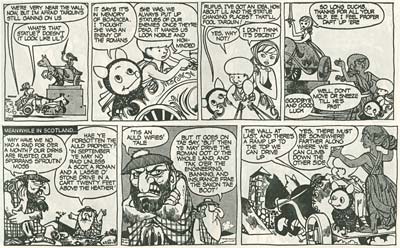

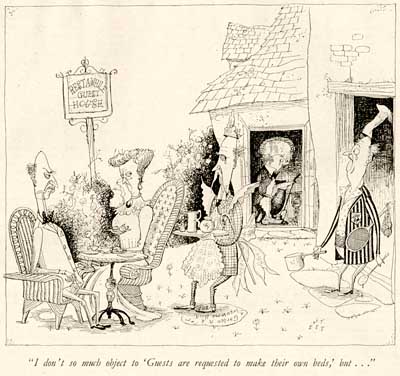

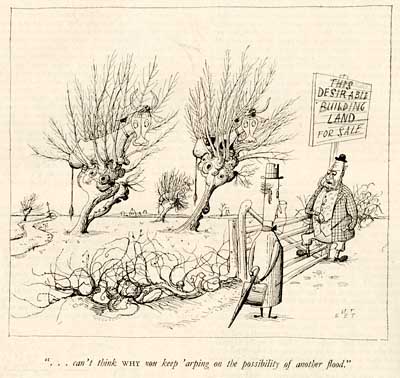

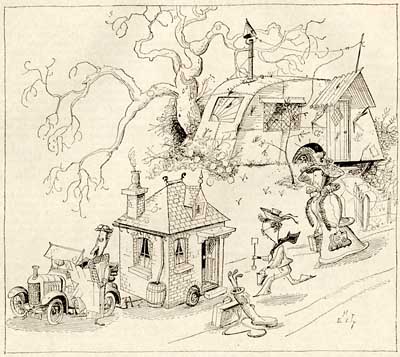

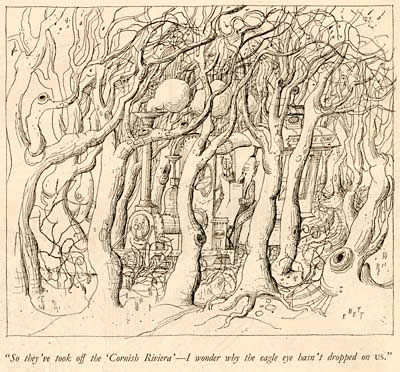

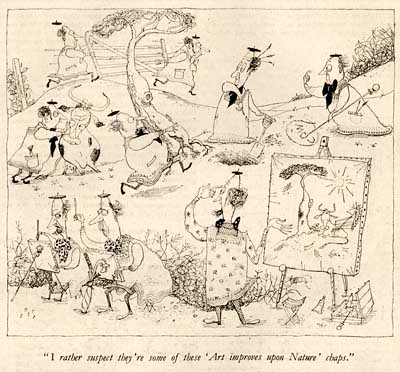

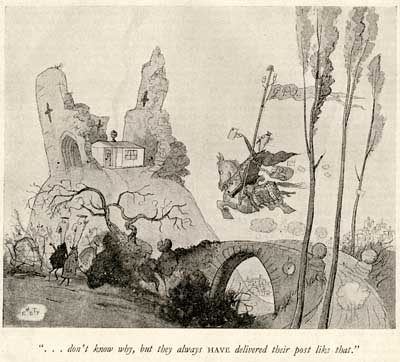

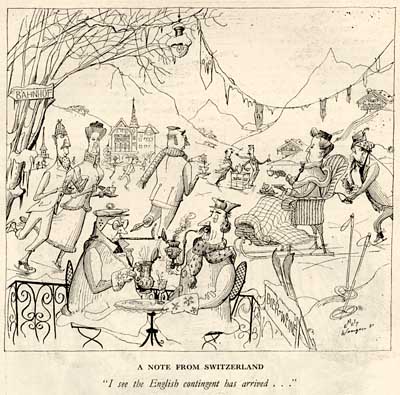

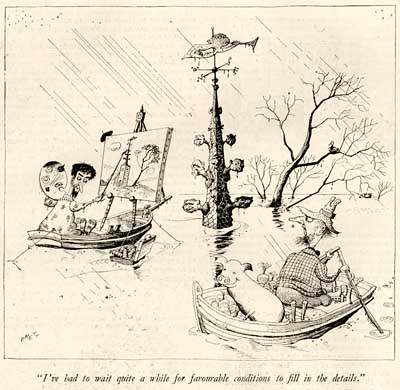

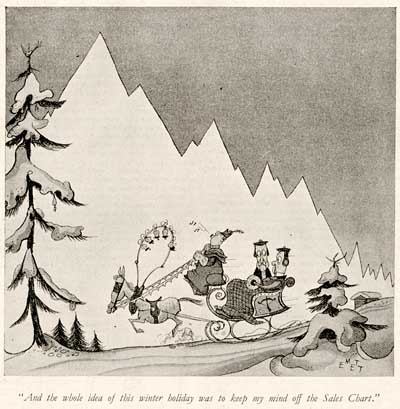

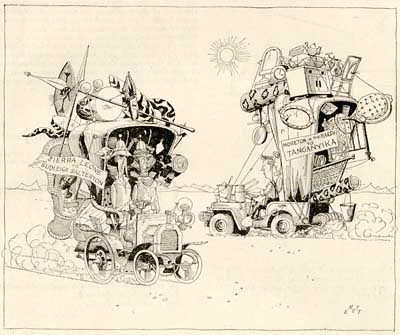

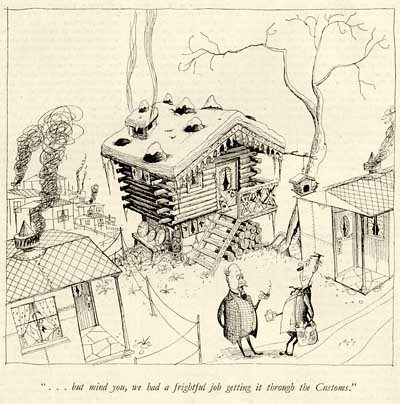

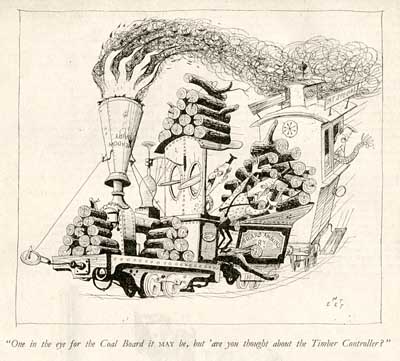

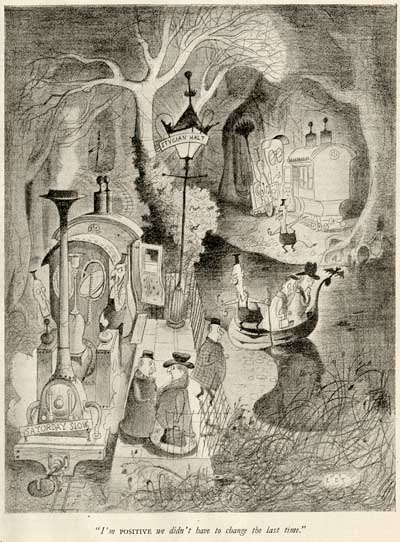

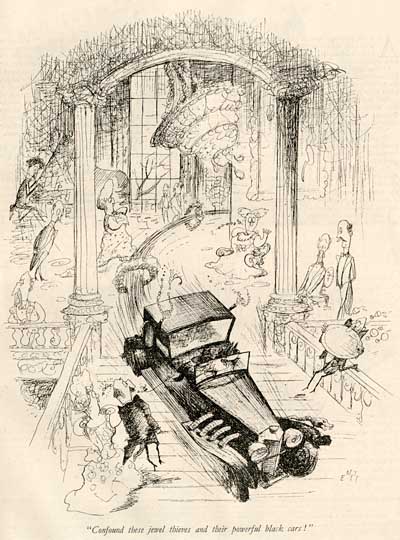

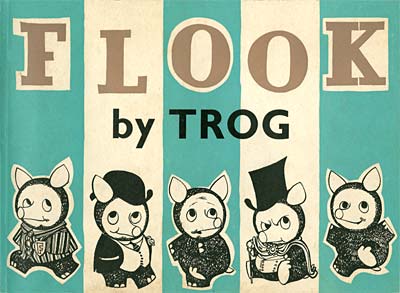

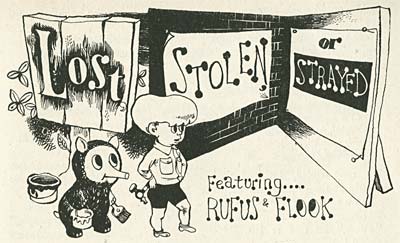

![]() Today, I’m posting a complete story by a comic strip artist whose name won’t be familiar to you unless you grew up in England in the 50s and 60s… he went by the name of "Trog". The nickname, short for "Troglodyte", came from his days hunkered down in air raid shelters during WW2. His real name is Wally Fawkes, and he’s one of those artists who has had two equally noteworthy careers- one as a cartoonist and the other as a Jazz musician.

Today, I’m posting a complete story by a comic strip artist whose name won’t be familiar to you unless you grew up in England in the 50s and 60s… he went by the name of "Trog". The nickname, short for "Troglodyte", came from his days hunkered down in air raid shelters during WW2. His real name is Wally Fawkes, and he’s one of those artists who has had two equally noteworthy careers- one as a cartoonist and the other as a Jazz musician.

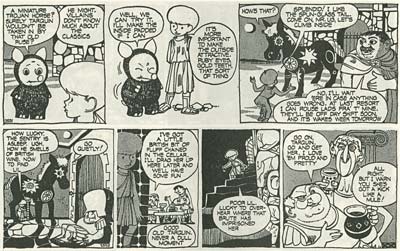

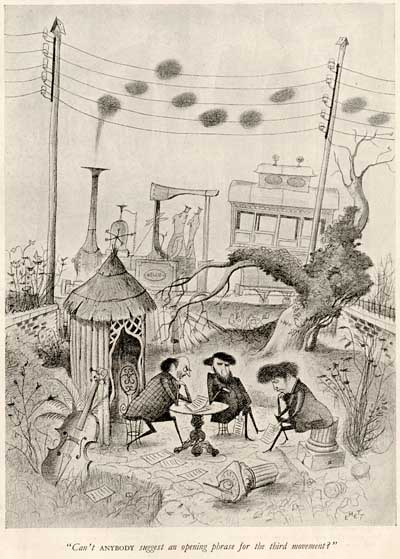

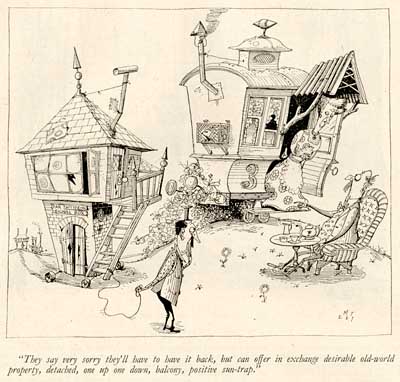

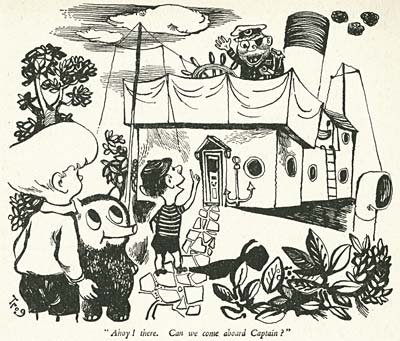

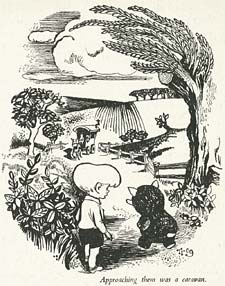

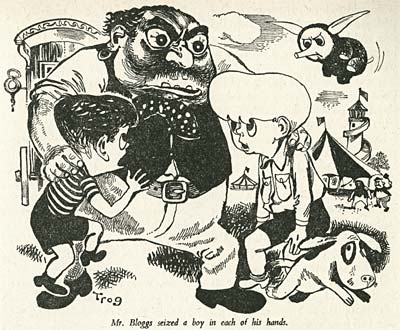

![]() Fawkes played clarinet in Humphrey Lyttleton’s jazz band in the 40s and 50s, and was one of the finest Jazz musicians in Britain. But in 1956, he launched a simultaneous career as a cartoonist, which brought him even more fame. “To cartoonists, I was always the one who played jazz. To musicians, I was always the one who drew cartoons.” he once said. But his talent for capturing personality through caricature was his strongest suit. Fellow artist, Nicholas Garland wrote of his political cartoons, "Very few artists can see a likeness the way he can, and catch it so completely. He doesn’t develop a hieroglyph for each politician and then simply reach for it each time it is needed. Every Trog caricature is carefully recrafted." You can see this in the story that follows in this post. Trog doesn’t simply copy the caricatured heads from panel to panel. He’s able to convey the essence of the caricature from a different angle in almost every frame.

Fawkes played clarinet in Humphrey Lyttleton’s jazz band in the 40s and 50s, and was one of the finest Jazz musicians in Britain. But in 1956, he launched a simultaneous career as a cartoonist, which brought him even more fame. “To cartoonists, I was always the one who played jazz. To musicians, I was always the one who drew cartoons.” he once said. But his talent for capturing personality through caricature was his strongest suit. Fellow artist, Nicholas Garland wrote of his political cartoons, "Very few artists can see a likeness the way he can, and catch it so completely. He doesn’t develop a hieroglyph for each politician and then simply reach for it each time it is needed. Every Trog caricature is carefully recrafted." You can see this in the story that follows in this post. Trog doesn’t simply copy the caricatured heads from panel to panel. He’s able to convey the essence of the caricature from a different angle in almost every frame.

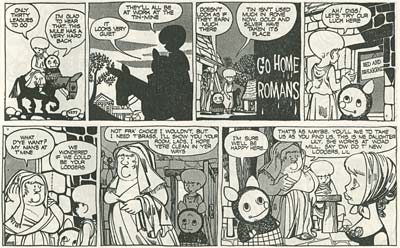

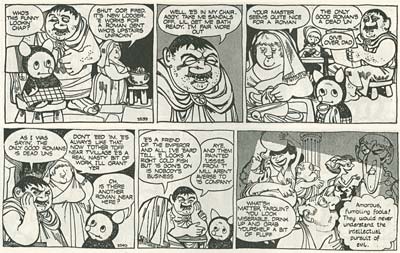

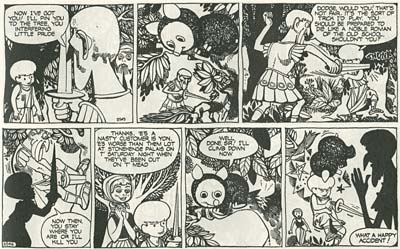

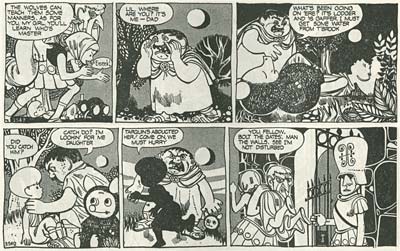

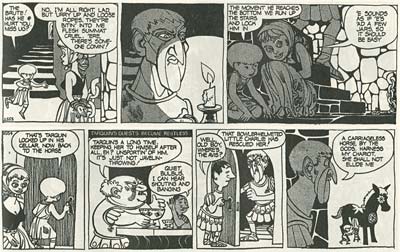

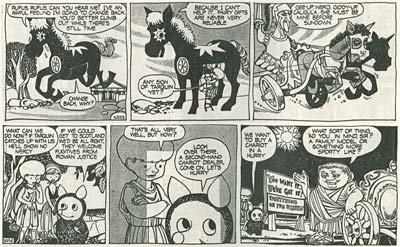

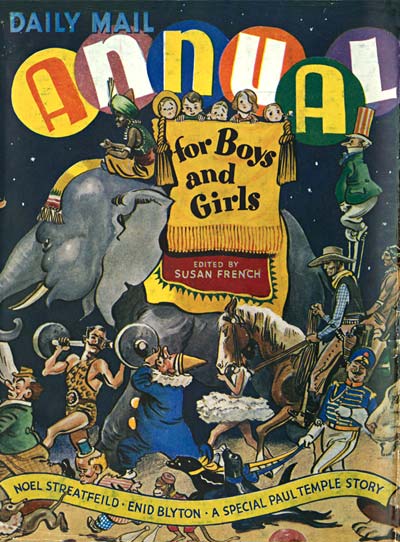

![]() Rufus and Flook continued in the Daily Mail for 40 years, until Trog’s jabs at Margaret Thatcher earned him the scorn of the paper’s conservative editorial staff. He never took censorship personally though. In 1977, when one of Trog’s political cartoons of Cyril Smith was rejected, and he simply shrugged his shoulders and said, “It’s their paper." After leaving the Daily Mail,Trog moved on to the Mirror and the Sunday Telegraph until his failing eyesight forced him to retire from his art career in 2005 and pick up the clarinet again.

Rufus and Flook continued in the Daily Mail for 40 years, until Trog’s jabs at Margaret Thatcher earned him the scorn of the paper’s conservative editorial staff. He never took censorship personally though. In 1977, when one of Trog’s political cartoons of Cyril Smith was rejected, and he simply shrugged his shoulders and said, “It’s their paper." After leaving the Daily Mail,Trog moved on to the Mirror and the Sunday Telegraph until his failing eyesight forced him to retire from his art career in 2005 and pick up the clarinet again.

![]()