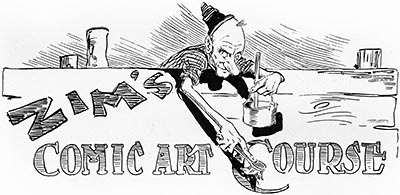

Every other month, members of Animation Resources are given access to an exclusive Members Only Reference Pack. In January 2015, they were able to download this wonderful e-book of the first volume of Eugene Zimmerman’s Cartooning Course. Our Reference Packs change every two months, so if you weren’t a member back then, you missed out on it. But you can still buy a copy of this great e-book in our E-Book and Video Store. Our downloadable PDF files are packed with high resolution images on a variety of educational subjects, and we also offer rare animated cartoons from the collection of Animation Resources as downloadable DVD quality video files. If you aren’t a member yet, please consider JOINING ANIMATION RESOURCES. It’s well worth it.

CLICK to Buy This E-Book

FOREWORD By Ralph Bakshi

FOREWORD By Ralph Bakshi

I grew up in a time, in the middle of the 20th century, when most drawings in cartooning- magazine gag panels, comic strips and animation– were all formula. The same funny character shapes were repeated over and over again. This was called "having a great style".

I didn’t realize that a great part of the history of cartooning had been lost until my wife Elisabeth and I stumbled across this complete set of Eugene Zimmerman’s cartoon course at an estate sale. Subsequently, and with great enthusiasm, I ran around from one book store to another looking for old copies of Judge and Life, the magazines that Zim had drawn for fifty years earlier.

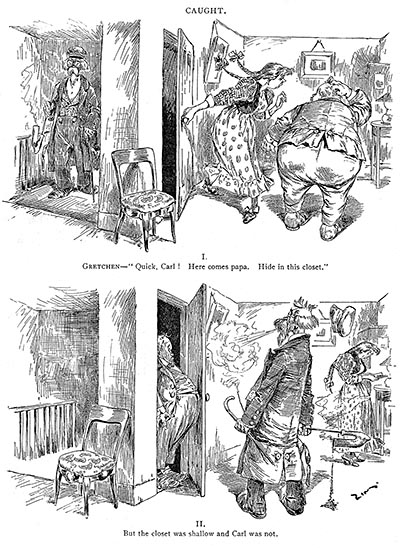

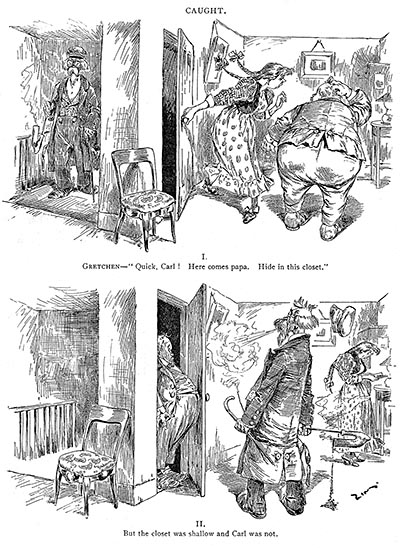

The thing that made Zim so great was that like all great artists, he had no formula for drawing. He thought about each drawing as it related to life and situation, then caricatured it. He didn’t have a simple cartoon formula to explain everything. He searched for the individual truth of the moment. At all times, his cartoons are hilariously funny and ring true. We recognize the event, the person, his age, social standing and ethnic type immediately. This is what makes his cartooning great.

Zim caricatured all of the people that we know so well. They were just like the people I grew up with in Brooklyn. His characters make me roar with laughter and appreciate all of our individual humanity. Zim’s drawing of objects– a shoe, a can, a pot, a chicken, a chair– come alive in his drawings. Each object has its own unique personality, just like his characters. To Zim, everything is funny and real at the same time.

So here is Zim’s cartooning course. How lucky can you get?

Ralph Bakshi March, 2009

CLICK to Buy This E-Book

INTRODUCTION by Stephen Worth

INTRODUCTION by Stephen Worth

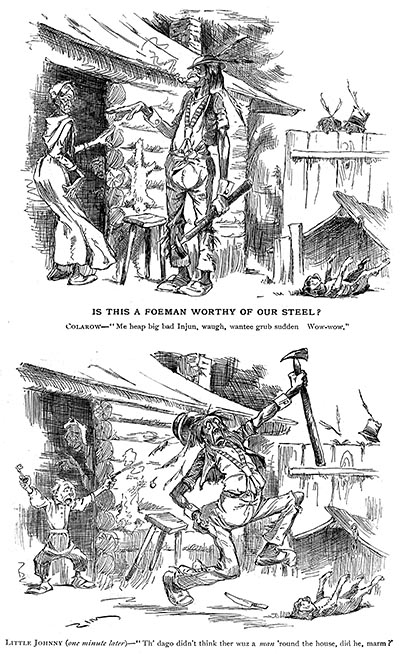

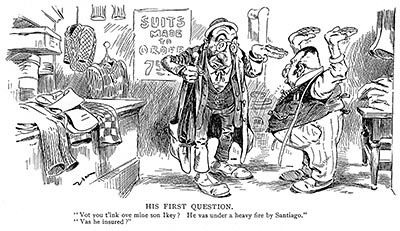

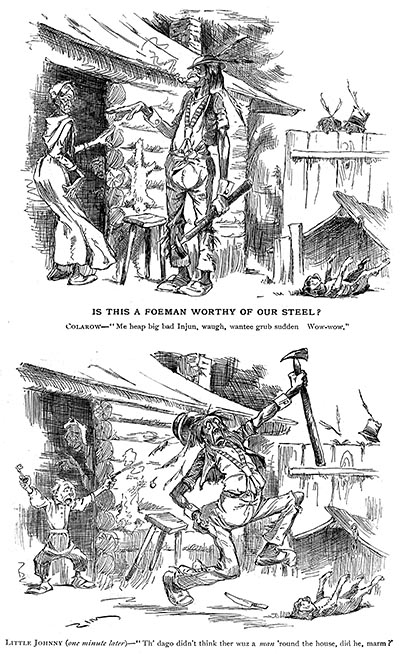

A century has passed since he hit his artistic peak, and perhaps because of that wide gulf, it is impossible to discuss the work of Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman without discussing the issue of race. The result of this is that Zim’s pioneering body of work has been largely misunderstood, or worse yet, completely erased from the history of cartooning.

In his introduction to ZIM: The Autobiography of Eugene Zimmerman (1988), Walter M. Brasch quotes Dr. Charles Press, professor of political science at Michigan State University. Press, the author of a book titled, The Political Cartoon, describes Zim’s work as…

…the kind of comic art where the last panel shows someone’s feet up in the air with the big word “plop!” It is at its most typical, characteristic of “correspondence school art.” The artist simplifies by offering clichés– “here is the way you draw a shoe, here is the way you draw an ear.” The clichés extend beyond the characters as well. Not only are the Jew and the Black drawn as stereotypes, but so are the English gentleman, etc. They all look like figures out of an unimaginative central casting.

Brasch attempts to explain why Zim has been forgotten…

By holding minorities up to ridicule, Zim had held all Americans up to ridicule– the minorities for the comic humor, the others for having allowed it. In an effort to cleanse a nation’s history, perhaps America deliberately tried to bury its past– and that included all art by all writers who used the stereotypes, even if much of their work was nonracist.

It’s obvious why critics and historians have swept Zim under the rug— they see only the ethnic gags on the surface of Zim’s cartoons. They don’t see the keen observation, artful exaggeration and underlying humanity that makes a Zim cartoon so much more than just a simple joke based on racial differences. This is understandable for a historian whose principle focus is on social issues. But the surprising thing is that most artists and cartoonists have forgotten about Zim as well.

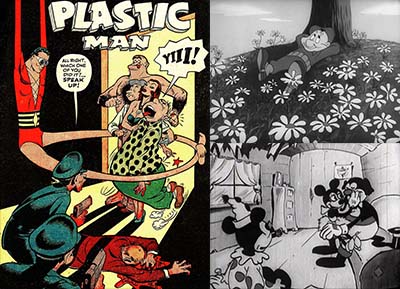

Overviews of the history of cartooning routinely begin with Wilhelm Busch and Thomas Nast in the 1860s, then jump forward to the introduction of newspaper comics with Outcault’s “The Yellow Kid” thirty years later. The decades between yawn like a black hole in the timeline. One might be led to believe that nothing much of importance took place in the interim. But the truth of the matter is, there were many great cartoonists and illustrators who lived and worked during that forgotten time— Joseph Keppler, A. B. Frost, Frederick Opper, Bernhard Gillam, James Montgomery Flagg, T. S. Sullivant and Eugene Zimmerman. These artists laid the foundation for everything that followed.

I first encountered Zim’s art in a bound volume of Judge magazines dating from shortly before the United States entered World War I. By this time, Zim had already left the Judge staff to work freelance from his home in Horseheads, NY and his contribution to the magazine was minimal. His cartoons consisted of tiny characters slipped into the margins of the columns, much like Sergio Aragones’ doodles in Mad magazine many decades later. But even tiny and simplified, the vitality of his characters leapt off the page at me. It was clear that here was an artist worth investigating.

I began combing the online resources and used bookstores, but it was difficult to find information. However, when I mentioned Zim to my friend, Ralph Bakshi, his voice boomed through the telephone— “ZIM! Ha! Ha! You found Zim! I was keeping him as my secret!” Ralph explained that he had stumbled across a copy of Zim’s cartooning course in the late 1960s, and kept it close at hand as he created his first few animated features— Fritz the Cat (1972), Heavy Traffic (1973), and most importantly, Coonskin (1975). Ralph had kept his interest in Zim to himself all those years, but now he enthusiastically shared his thoughts with me, and allowed me to digitize rare material from his library. The puzzle pieces began to come together to reveal the true genius of this overlooked master of the art of caricature.

Caricature consists of equal parts observation and exaggeration. Zim was adept at both. In his autobiography, Zim tells a story about one of his outings to find subjects to caricature…

When the instantaneous camera was invented, the Judge Company bought one as an experiment, or perhaps took it in exchange for advertising. It was in the form of a stiff false vest front covered with suiting, at the time fancy vests were in vogue. The camera was a flat, nickel-plated circular affair with a revolving plate capable of holding eight pictures and which operated automatically when the shutter closed. It was intended as a detective camera. You could approach a person and, with one hand in your trousers pocket, pull a string which led into the pocket, operating the shutter.

Hamilton and I were slumming for character studies one day and experimenting with the new little plaything. The first human to strike our fancy was an aged woman scavenger whose upper part was buried in a barrel of rubbish, with the rear elevation conspicuously aimed at us. After taking a couple of preliminary shots, we desired a study of the face as well, so Hamilton told me to get ready, and let out a tremendous yell. The woman jumped clear of the barrel. I pulled the string, got her face and quickly left the neighborhood, followed by a whole paragraph of the most exquisite profanity that ever warbled from the throat of a filthy bird.

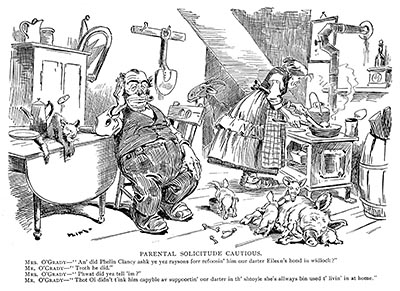

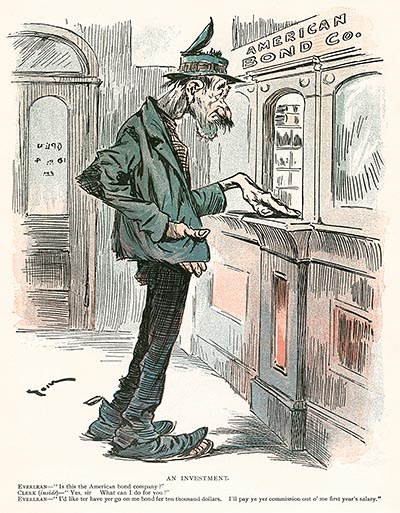

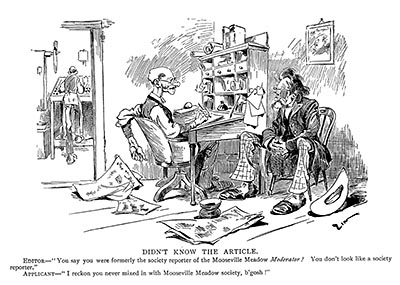

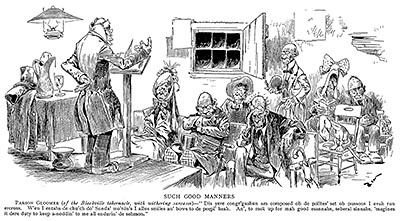

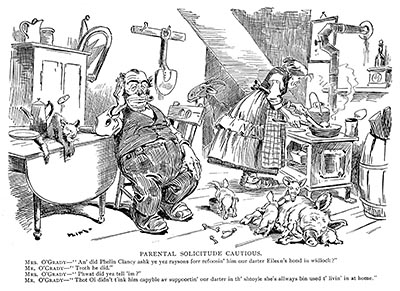

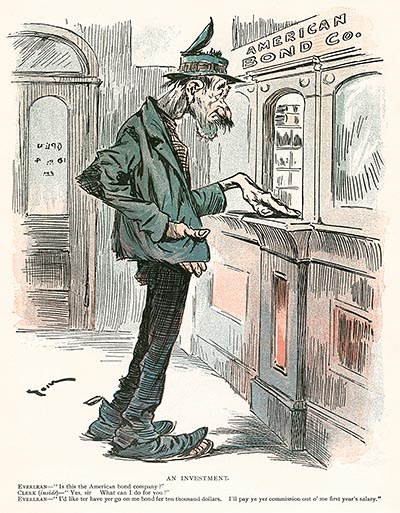

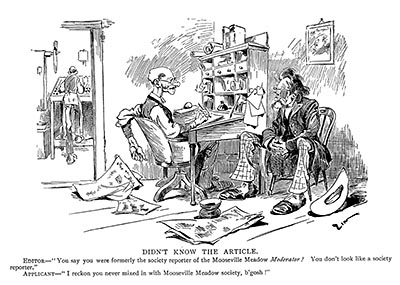

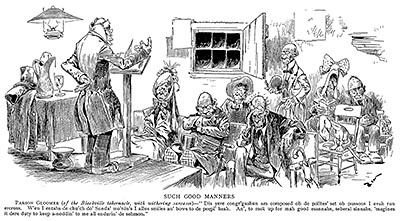

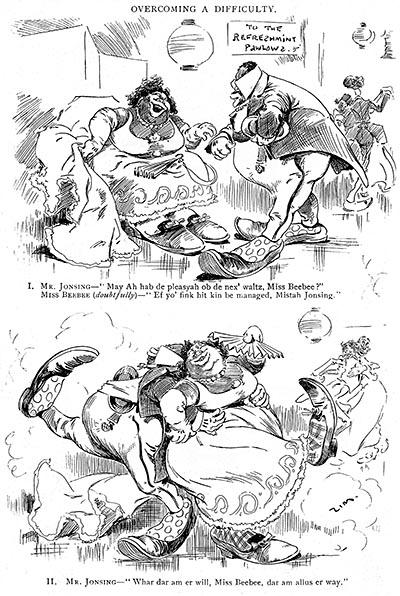

The level of specificity of detail in the clothing, architecture and attitudes of the characters in Zim’s cartoons reveal that he wasn’t just recycling clichés or stereotypes, he was drawing upon keen observation of the world he saw around him. Then, as now, the most exaggerated and interesting characters resided in the poorer neighborhoods, and in the 1890s, New York City contained a particularly wide palette of character types to study.

Before Zim entered the scene, caricature was reserved for the powerful and well-to-do. The cartoons in Life magazine featured men in tuxedos and top hats and women seated on sofas in palatial sitting rooms. All of the humor was contained in the caption, and the formulaic artwork was based more on an abstract concept of “good taste” than it was on anything remotely real. Puck magazine generally focused on politicians and public figures, taking a hard-hitting approach to current events. But Zim looked to the common man for inspiration. His work reflected the dynamic nature of the American melting pot better than any other artist of his day.

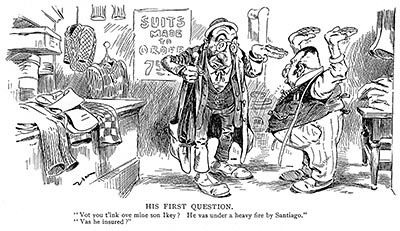

Zim exaggerated the ethnic differences he saw in the Irish, Black, Jewish and other immigrant neighborhoods of New York, but he didn’t just apply a stereotypical formula to his caricatures. Looking at Zim’s detailed images of everyday life among the various ethnic groups, one is struck by the amount of individuality among the characters. Each person is a unique personality, exaggerated to enhance his own peculiar characteristics.

There is an important distinction to be made between clichéd stereoptyping of ethnic groups and the sort of observational caricature that Zim excelled at— the difference is honesty. Although the gags and dialogue occasionally strayed into routine formulas, Zim’s drawings never did. In his cartooning course, Zim spoke about the constraints sometimes placed upon him by the editorial staff…

An artist is not always the father of the joke attached to his drawing. Very often, an art editor accepts an idea or suggestion which is without a picture; thus the artist is requested to make a drawing to correspond with the idea. Now it may happen that the art editor and the artist differ in their conception of humor and inasmuch as the art editor’s opinion predominates in this case, the artist proceeds to illustrate the joke as directed.

The general public, while not aware of these facts, lays all the blame on the artist, and the artist must cheerfully accept the public’s condemnation. It has been my custom in such cases to insert a lot of interesting detail to make the drawing as catchy as possible, in order to hide the inferior quality of the joke.

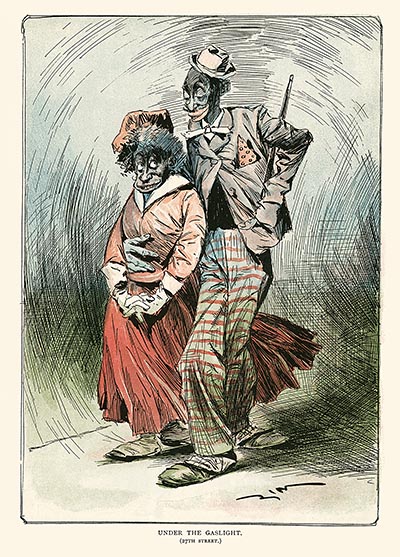

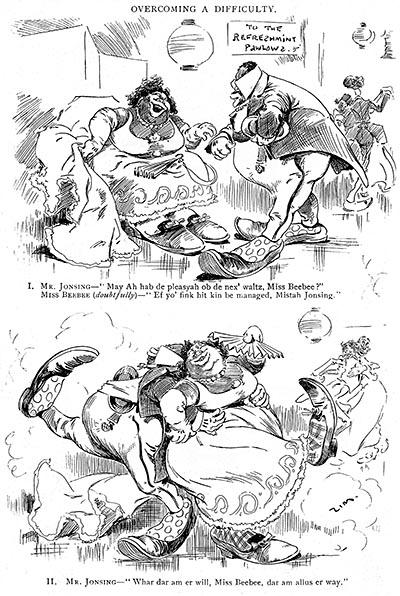

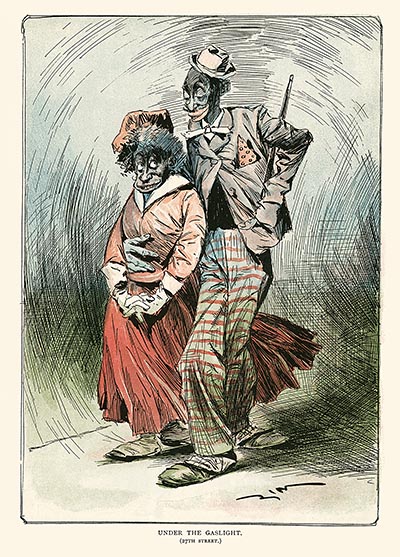

A likely example of this sort of thing is a cartoon from the January 1896 issue of Judge’s Library. A black couple out for a night on the town are shown “under the gaslight” on 27th street…

Armand (who has just proposed)— “Pore liddle honey,

yo’ looks blue! I’s ‘fraid yo’s cold.”

Pauline— “Dat ain’t cold, Gawge. Dat’s blushes!”

Zim makes no attempt to literally illustrate the gag— there is no blue cast to the blush on the girl’s cheeks. Instead, he pours all of his powers into capturing a moment. The boy, a dandy, has a cane tucked casually in his pocket and a hat perched on his head at a jaunty angle. His body is posed in such a way that we can discern the proud way he walks. The girl looks up to him shyly with an admiring glance out of the corner of her eye. The wind blows through her skirt, and the boy’s hand wraps around the girl’s waist holding her close.

But the most interesting detail isn’t obvious on first glance… the boy’s trousers are decorated with an American flag. Cartoonists at this time didn’t treat the flag lightly— its use served a specific purpose. Zim is depicting this Black couple as a typical American boy and girl out on a date. When you consider that Blacks had been slaves just few decades before, this simple image takes on a wider significance. Zim’s cartoon documents how Blacks at the time were making their first entry into mainstream American society. The silly gag sits below the frame in the dialogue, completely irrelevant to Zim’s eloquent image.

Zim didn’t ridicule his subjects; he caricatured them. The point of caricature is to use humor and exaggeration to illuminate truth. The fact that he made fun of so many types of people reveals that he held no special animosity against any particular group. He poked fun at everyone equally. And although he exaggerated the surface differences between people, he always kept his focus on portraying the essential truth at the core of his caricature.

In his last “how to” cartooning book, How To Draw Funny Pictures (1928), Zim sums up his philosophy of caricature like this…

When you see a haughty person, do not be deceived into believing that it is some great man or famous woman out for a walk. More likely it is some fickle waitress or a pool hall loafer who won $3.00 in a crap game or inherited $47.60 from a dead aunt. Or possibly it may be some haughty clerk out showing off the latest dollar-down-and-dollar-a-week clothing. The really great are never haughty. My work and travels have brought me into contact with the great and near-great in all lines of endeavor— presidents and movie actors, authors and artists, Buffalo Bill and Bryan, Edison and Lindbergh— they were all hearty and unassuming.

Greatness makes one tolerant. Great men are not ashamed to stop on the street and talk to the man in overalls. They recognize the bond of friendship between the common people and themselves. The social sheik who feels above talking to a mere laborer is fooling only himself.

Take this little sermon to heart and treat every man as your equal; it will help you to get ahead. How truly the Bible says, “The greatest among you shall be the servant of all.”

In our “politically correct” times, it is easy to look at the surface details of Zim’s cartoons and miss the humanity that courses through them just under the surface. Zim’s Correspondence School of Cartooning, Comic Art & Caricature is more than just lessons in how to draw. It’s a philosophy of what it means to be a cartoonist.

My purpose for compiling this book is to serve two purposes… First, I want to shine a spotlight on a forgotten artist whose work helped to lay the foundation for the whole history of cartooning. Secondly, I want to encourage current artists to consider Zim’s philosophy and apply his keenly observed honesty to their own work.

I would like to thank Ralph Bakshi, the Horseheads Historical Society, and the dedicated crew of volunteers at the Animation Resources for their invaluable assistance. I hope you find this book to be useful.

Stephen Worth

Director, Animation Resources

March, 2009

CLICK to Buy This E-Book

Not A Member Yet? Want A Free Sample?

Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

by

by

![]()

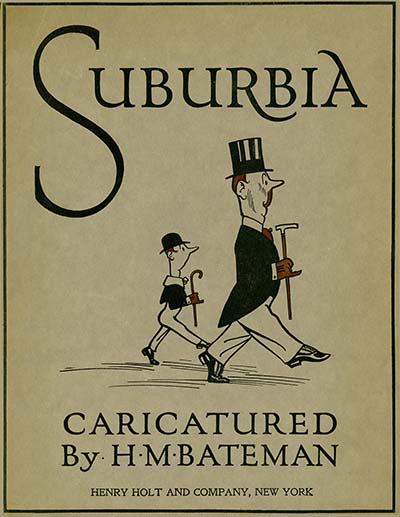

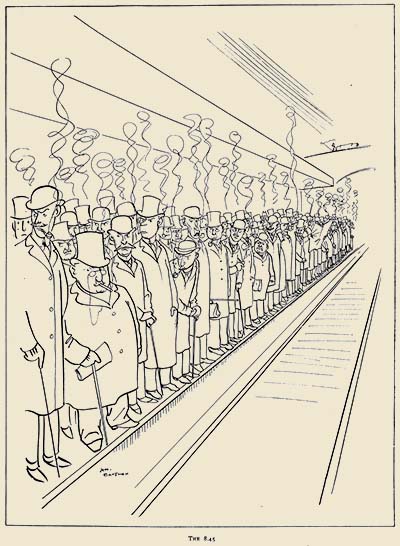

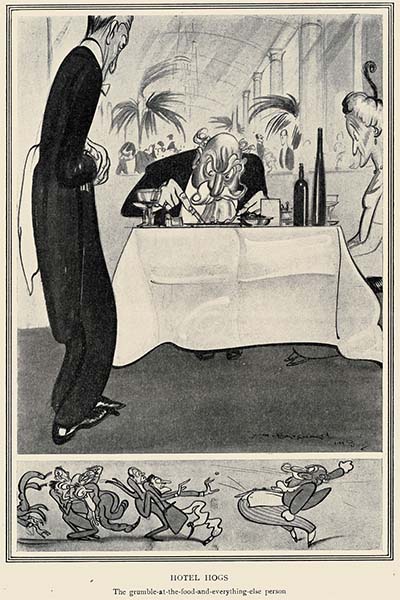

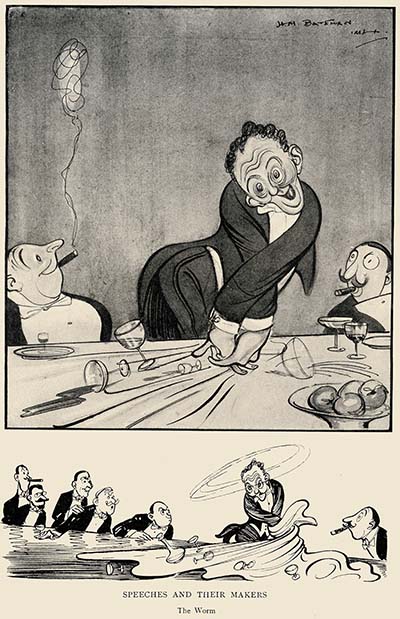

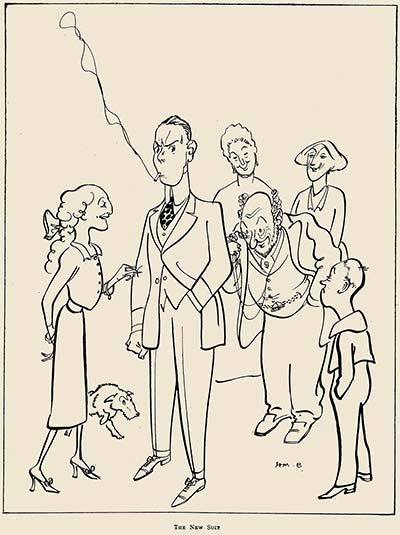

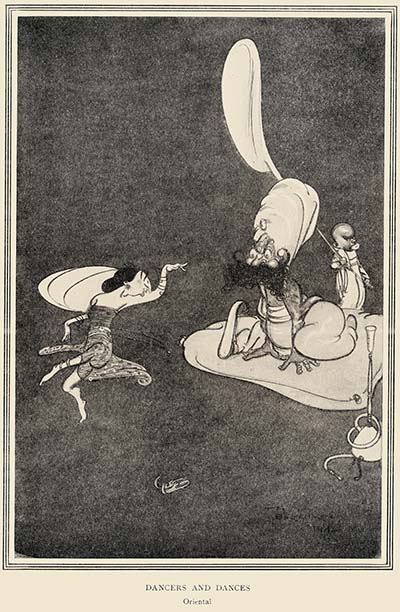

![]() Born in 1887, H. M. Batman was already drawing for publication in his early teens. Astonishingly prolific and inventive, everything he saw became material, so that his work can be read as a social history of Britain in the first half of the 20th Century and, to an extraordinary degree, as a kind of autobiography. His style developed and changed radically over the years. From the graceful and rhythmical lines of his earlier work to the stark brilliance of his strip cartoons and the furious energy of his "Man Who…" series, his essential qualities of superb draughtsmanship, astonishing observation and a profound appreciation of humanity’s foibles, are always married to a wonderful wit and narrative perfection. He told marvellously funny stories in pictures.

Born in 1887, H. M. Batman was already drawing for publication in his early teens. Astonishingly prolific and inventive, everything he saw became material, so that his work can be read as a social history of Britain in the first half of the 20th Century and, to an extraordinary degree, as a kind of autobiography. His style developed and changed radically over the years. From the graceful and rhythmical lines of his earlier work to the stark brilliance of his strip cartoons and the furious energy of his "Man Who…" series, his essential qualities of superb draughtsmanship, astonishing observation and a profound appreciation of humanity’s foibles, are always married to a wonderful wit and narrative perfection. He told marvellously funny stories in pictures.![]()