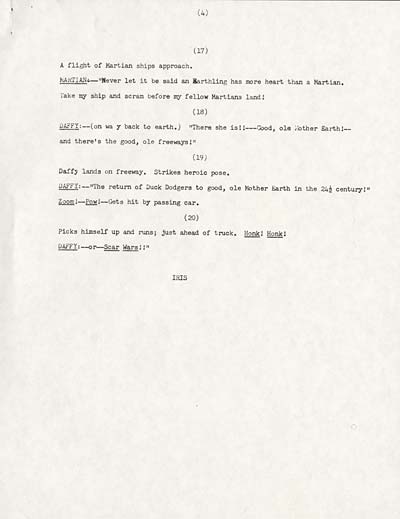

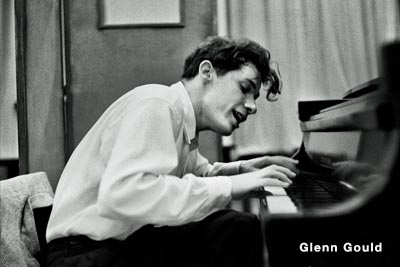

Glenn Gould was one of the foremost pianists of the 20th century. Best known for his interpretations of Bach, Gould hosted a series of radio programs for the Canadian Broadcasting Company. This article comes from a program by Gould on Leopold Stokowski.

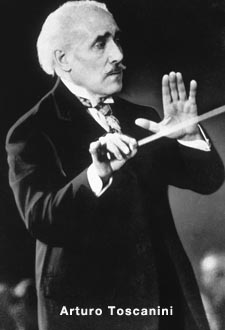

When I was a teenager back in the 40s, Leopold Stokowski shared for some years the podium of the New York Philharmonic. His co-director was the late Dimitri Mitropoulis and together they contributed to that memorable Sunday afternoon series on CBS radio, which was one of the few redeeming features of American broadcasting in the years after World War II. Running opposite the Stokowski/Metropoulis programs on CBS was NBC’s entry in the symphonic sweepstakes, a series featuring the orchestra which bore the network’s name, which was created for and conducted by Arturo Toscanini.

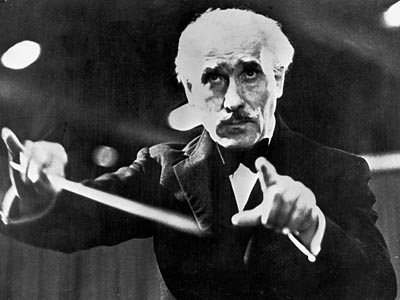

![]() The attitude of the young people of my generation toward these weekend music specials was rather interesting. It was generally bandied about by my conservatory friends that you were either a Stokowski fan or a Toscanini devotee. There was apparently no middle ground, except perhaps that which was occasionally occupied by Bruno Walter. According to the academic banter of that time, Toscanini embodied most progressive musical virtues. His performances were direct, straightforward and emotionally objective. Whichever notes, dynamic marks or tempo indications appeared before him in the score were, to the best of his and the NBC Orchestra’s ability, what you heard. For Toscanini, the composer’s notational suggestions were gospel.

The attitude of the young people of my generation toward these weekend music specials was rather interesting. It was generally bandied about by my conservatory friends that you were either a Stokowski fan or a Toscanini devotee. There was apparently no middle ground, except perhaps that which was occasionally occupied by Bruno Walter. According to the academic banter of that time, Toscanini embodied most progressive musical virtues. His performances were direct, straightforward and emotionally objective. Whichever notes, dynamic marks or tempo indications appeared before him in the score were, to the best of his and the NBC Orchestra’s ability, what you heard. For Toscanini, the composer’s notational suggestions were gospel.

YouTube: Toscanini conducts the overture to

La Forza del Destino (Verdi) 1944

Not so with Stokowski. He was and is, for want of a better word, an ecstatic. Stokowski is involved with the notes, the tempo marks, the dynamic indications in the score to the same extent that a filmmaker is involved with the original book or source which supplies the impetus- the idea of his film. So, Stokowski’s performances either stand or fall depending on the degree he can infuse them with a sense of his own commitment to the project. And happily for those who became addicted to his way of making music, there’s rarely been a more committed, more imaginative, more resourceful artist than Leopold Stokowski.

Leopold Stokowski conducts the second movement from

Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony (Carnegie Hall/1947) at YouTube

There was however another reason for the disrepute into which Mr. Stokowski’s interperative techniques had fallen in those years, besides that penchant for a neo-literalist performing style which the young people of my generation espoused. He was not only a popularizer- a man who thought nothing of transforming the keyboard works of Bach into massive orchestral statements. But more than that, he was a film personality. In the mid-1930s, he’d relinquished his post as the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, in which he single-handedly transformed the standards of orchestral playing in North America, in order to join Deanna Durbin and Donald Duck on the silver screen in Hollywood.

Stokowski from “Big Broadcast of 1937” at YouTube

“I go to a higher calling.” he was reported to have said to the press conference which was called to announce his departure, and if one can filter out the inevitable quotient of defensiveness which one may assume to infiltrate a remark of that kind, it was a remarkably revealing comment.

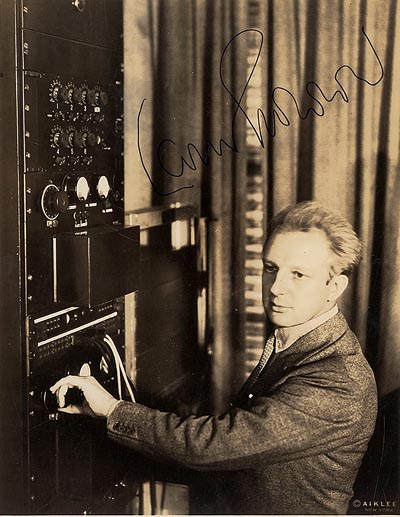

Technology for Stokowski was a higher calling. He was indeed the first great musician to realize that the future of music would inexorably wound up with technological progress, and that communications media were in fact the best friend that music ever had. Many of his recordings… and all of which I know from personal experience where he maintains a firm hand in relation to the processes of production… were years ahead sonically.

But the real benefit of his interest in technology, I think, was that it enabled Stokowski to resist the inhibitions induced by those pre-technological attitudes toward music-making which created the stratified roles of performer, listener and composer; and which held that those roles would ever remain separate and distinct. For Stokowski, I think, those distinctions are themselves are the single greatest danger that the artist must face. And I suspect that the enormous appeal of his music-making over the last sixty years or so is precisely his realization of that fact, and his willingness to act upon the assumptions that follow from it.

Bach’s “Passacaglia & Fugue in C minor” at YouTube

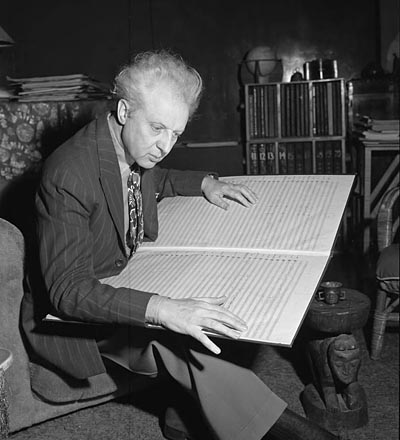

Stokowski is 88 now, at least he was when I interviewed him for this program. Nothing in his manner, his outlook or the vitality of his music-making suggests the incipient nonagenarian, but it’s perhaps useful to recall that Stokowski was born while Wagner was still alive, and when Brahms died, Stokowski himself was already a teenager.

In theory, his outlook and his art should represent the aesthetic attitudes of a bygone era, or eras. But in fact, because of his extraordinary warmth and humility, his remarkable receptivity to new ideas, and above all because in his lifetime we’ve already seen nothing but triumph. But the essential humanity of those technological ideas which have informed all of his work as a musician, Leopold Stokowski is very much a man of the future.

-Glenn Gould

Playlist of the entire Stokowski radio program at YouTube

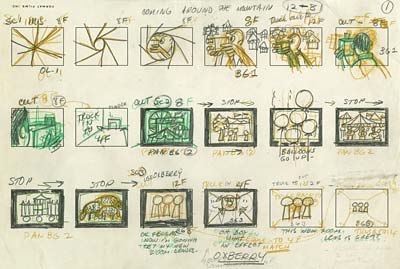

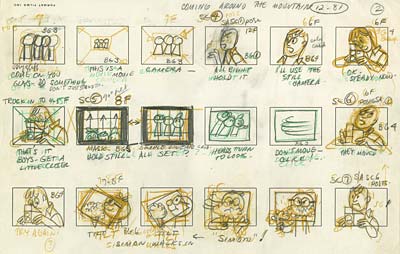

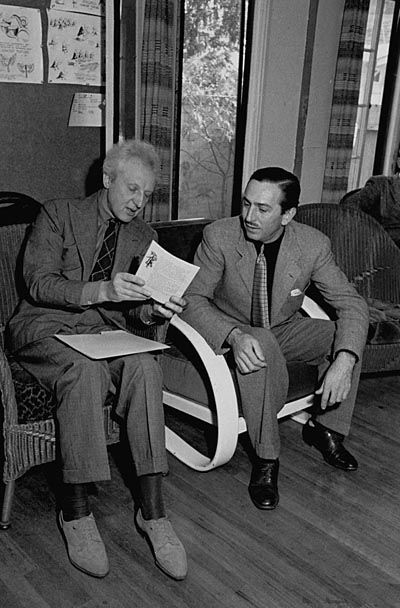

So, what is the connection to animation, you might ask… Well the obvious link is the fact that Walt Disney and Leopold Stokowski collaborated on Fantasia.

But it goes deeper than that. Stokowski shared certain creative instincts with some prominent animators. For instance, In the space of a little more than a decade, Stokowski built the Philadelphia Orchestra up from scratch until it was the preeminent orchestra in the United States. He employed the latest technology to bring the highest possible production value to his recordings. After he had reached the peak of popularity, he turned his attention to bring his music-making to a whole new media. He embraced motion pictures, radio broadcasts and television programs as a means to present his music in an entirely new way to the broadest audience possible.

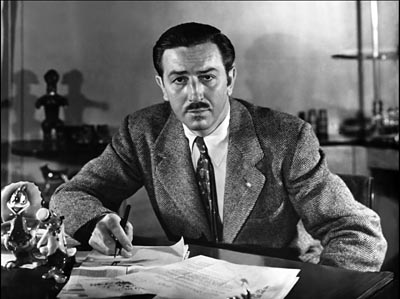

Walt Disney pressed his artistic staff to improve and develop new techniques for the art of animation, making huge strides between “Steamboat Willie” and “Snow White”. He employed Technicolor, the multiplane camera and live action/animation compositing to advance the tools available to his artists, which set his films apart from his competition on a technical level. After he had conquered the medium of the cartoon short with Mickey Mouse, he turned his attention to creating the first hand drawn animated feature. And when that was established, he turned to live action films, television and theme parks to take his ideas to new mediums. He succeeded in reaching the entire world with his creations.

In the article above, Glenn Gould touches on the differences between Arturo Toscanini and Stokowski. Toscanini was a disciplined conductor who demanded and got complete control. He unified a group of over 80 musicians into a single mind, expressing the will of Toscanini. This resulted in performances of incredible directness and power. Toscanini’s aesthetic choices were consistent and were handed down as the law through the regimented beat of his baton.

In contrast, Stokowski was more of a magician, evoking a unique performance out of each and every musician in his orchestra. Instead of deciding on a plan of attack in advance and executing it with precision, Stokowski allowed for the inspiration of the moment to guide him. He was constantly experimenting and evolving as an artist. His carefully modulated hand gestures directed the ebb and flow of the performance without rigidly controlling it. Even without a rigid hand controlling the proceedings, he could take an orchestra with which he had never worked before and quickly lead them to that distinctive “Stokowski Sound”.

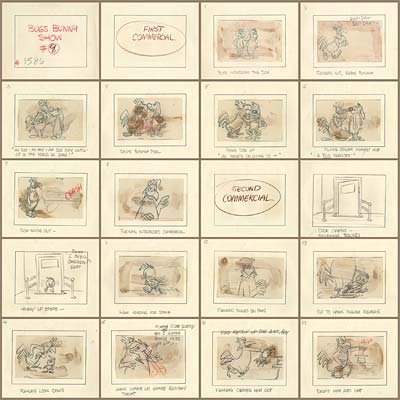

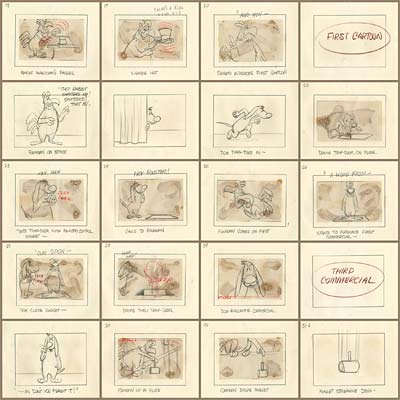

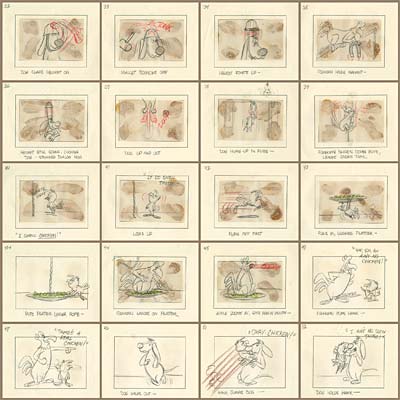

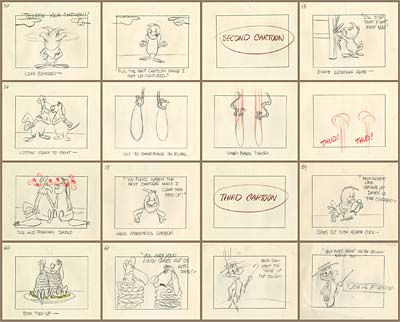

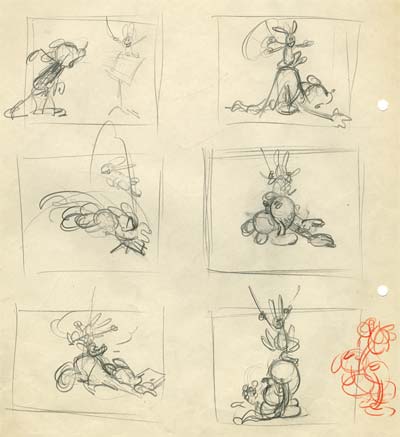

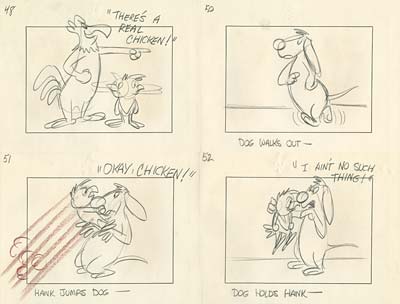

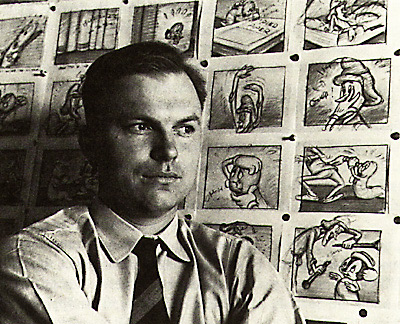

Chuck Jones was a director of animated cartoons who planned out his films in great detail at the layout stage and required his animators to hew close to his drawings in their scenes. He precisely controlled every aspect of the timing of his films, and as he developed his characters, he created a canonical set of rules for the story structures and the way the characters acted within them. His Roadrunner and Pepe Le Pew cartoons were more like variations on a single theme than individual cartoons because they were constantly refining and focusing the specific ideas of Chuck Jones.

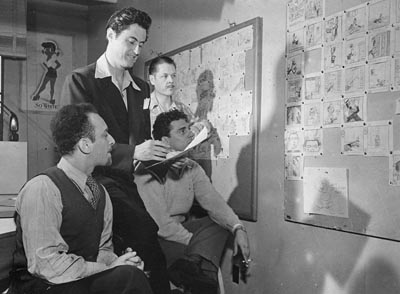

Bob Clampett approached the direction of his films quite differently. Instead of insisting that the artists draw precisely the way he did in the layouts, he encouraged them to go beyond his drawings and work within their own style to express themselves in the most creative way possible. Robert McKimson was encouraged to create scenes of great solidity and strength, while Rod Scribner was directed to explore the fourth dimensional aspects of cartoony exaggeration. This freedom didn’t result in a dilution of Clampett’s control over the film. On the contrary, he used his artists’ strengths and weaknesses to put across his own unique vision and sense of humor. There were no rules in Clampett cartoons. In one, Bugs Bunny would be the victor, in another, he would be foiled at every turn. Each film was developed as its own creative experiment, and the variety of moods, stories and atmosphere in his films is kaleidoscopic.

Both Toscanini and Stokowski were great conductors. In fact, they may have been the two greatest artists ever to work in their artform. But they were as different as they could possibly be. The same might be said of Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett.

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit entitled Theory.

FEATURED EXHIBIT

Music shares an indescribable magic with animation. It’s hard to describe in words exactly why certain walk cycles or pantomime gags are so wonderful. Music is a source of non-verbal delight as well. The rhythms and pacing of cartoons often mirror the construction of popular music with a statement of theme followed by variations, culminating in a restatement of the theme and a big finish. If you think about it, the best cartoons are inseparable from music. Adventures in Music explores the wide world of music with an eye to revealing the relationships between music and creativity.