In the twenties, Gustav Tenggren had been paid handsomely for his work. At Disney, his position guaranteed steady work. But the wartime economy changed all that. Publishers were no longer able to pay him to work a week or more on a single painting and jobs were scarce. He was forced to simplify his style.

In the twenties, Gustav Tenggren had been paid handsomely for his work. At Disney, his position guaranteed steady work. But the wartime economy changed all that. Publishers were no longer able to pay him to work a week or more on a single painting and jobs were scarce. He was forced to simplify his style.

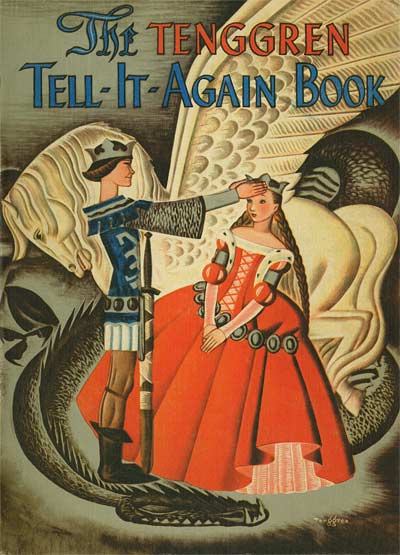

While at Disney, Tenggren chaffed under the bit of anonymity. It’s said that Walt instructed his artists, "If you’re going to sign a name to your artwork, spell it ‘Walt Disney’." But Tenggren defiantly maintained his individuality, signing many of his key paintings for Pinocchio. He left the studio under unhappy circumstances, and was bitter about the whole episode. But he had learned one thing from Walt… the power of branding one’s self.

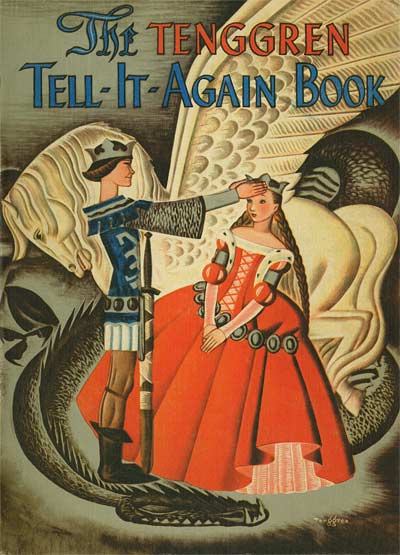

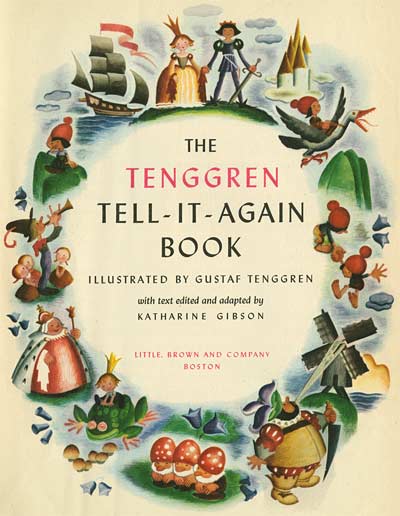

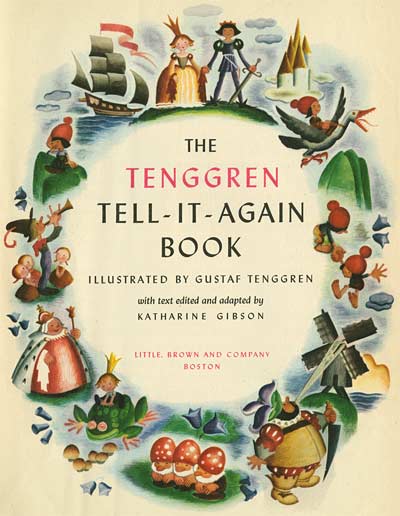

Tenggren resolved that he would never again waste his skills building a reputation for someone else. He boldly built his name into the masthead of his first major publication after leaving Disney. No longer was it

Andersen’s Fairy Tales or

Tales By The Brothers Grimm… It was

The Tenggren Tell-It-Again Book. This led to a series of self-titled books sprinkled throughout his career…

Tenggren’s Story Book, Tenggren’s Jack & The Beanstalk, Tenggren’s Bedtime Stories, Tenggren’s Farm Stories, and many others.

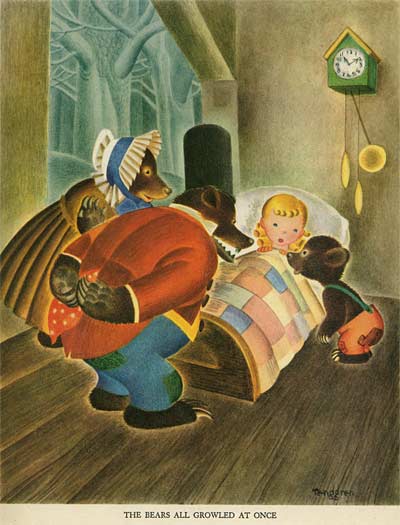

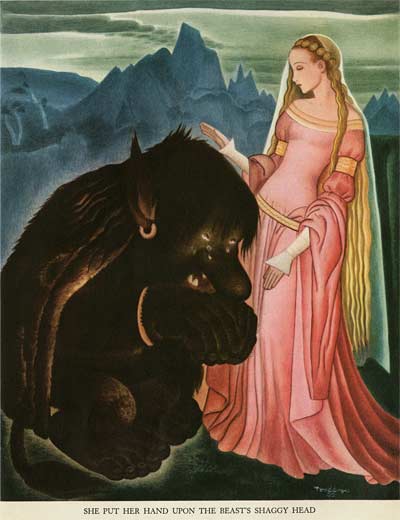

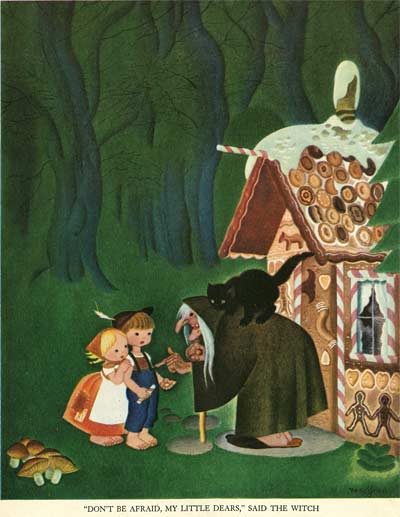

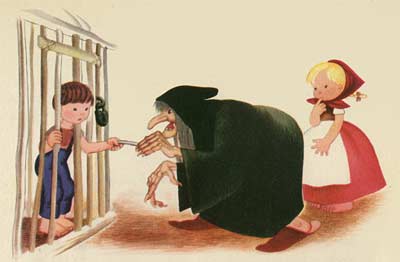

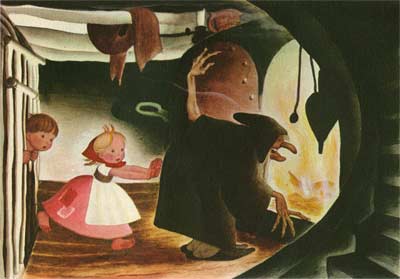

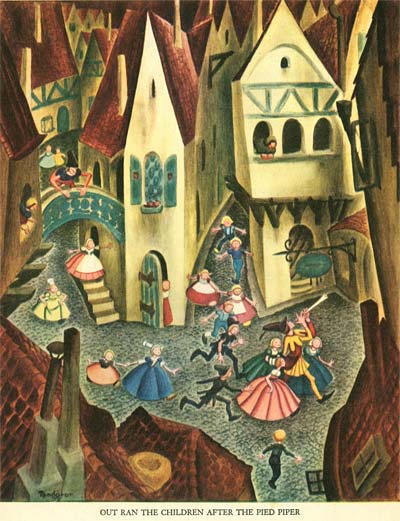

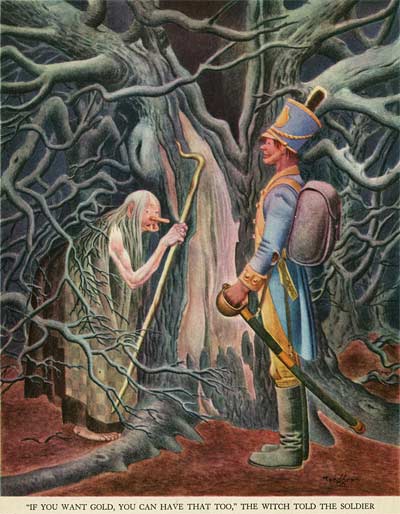

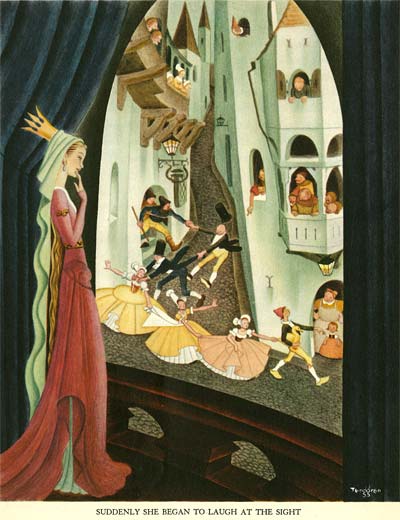

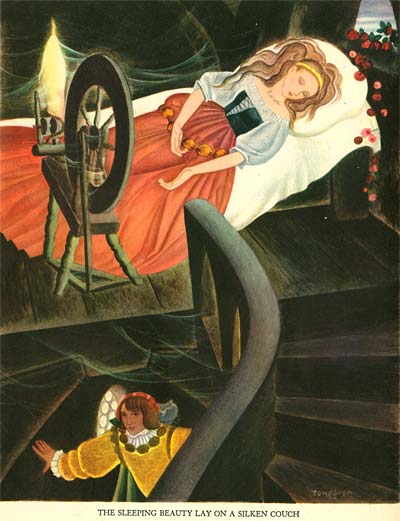

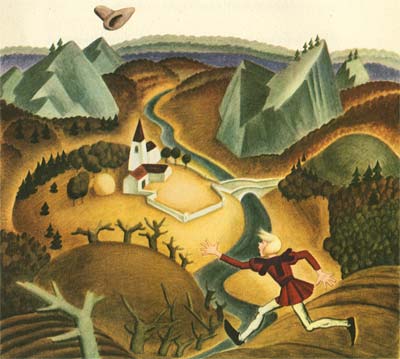

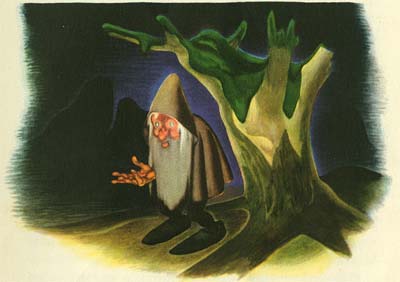

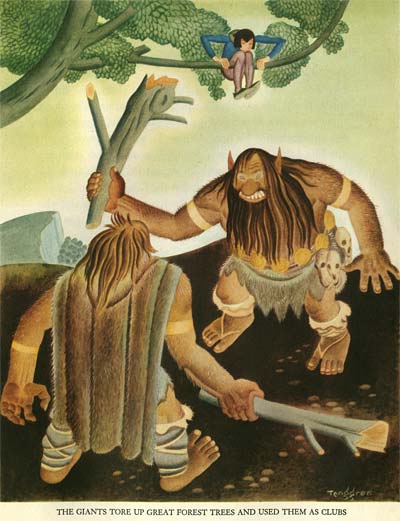

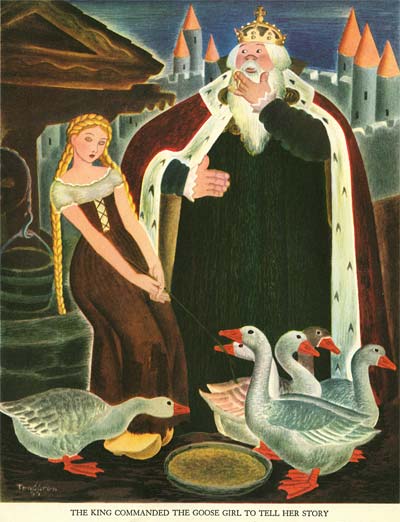

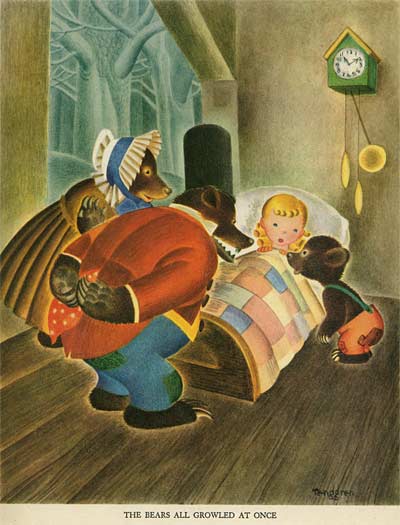

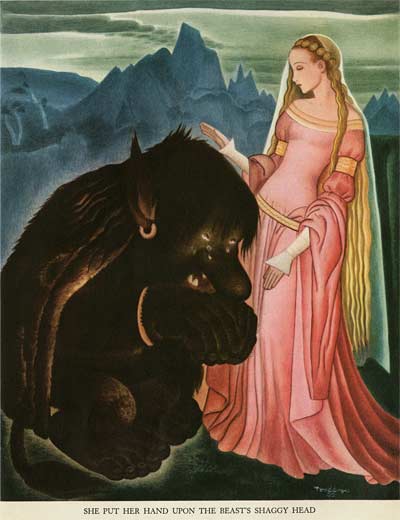

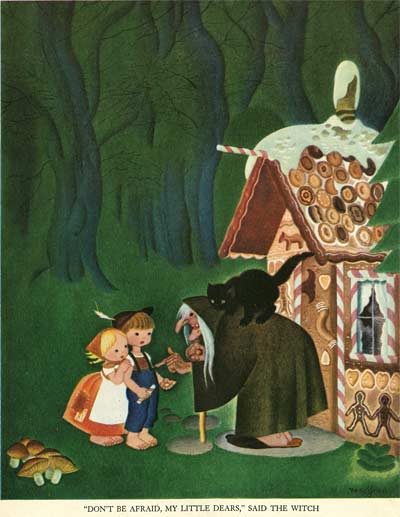

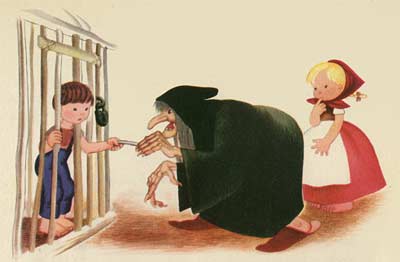

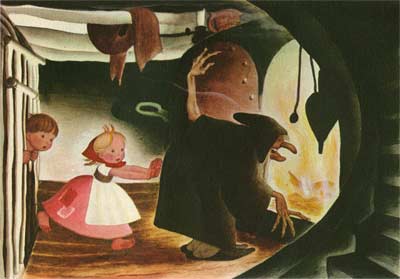

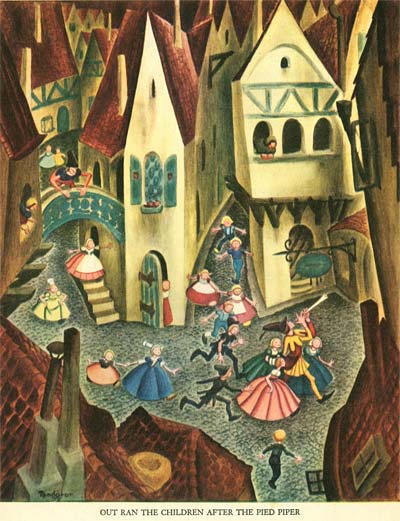

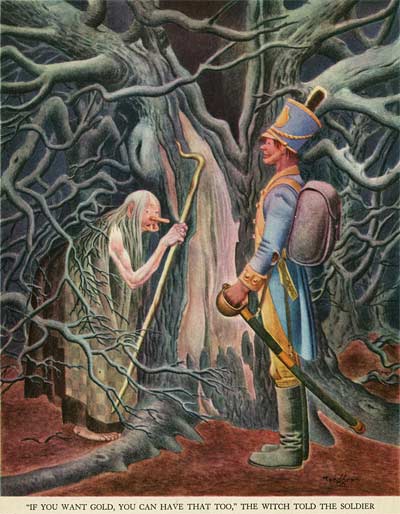

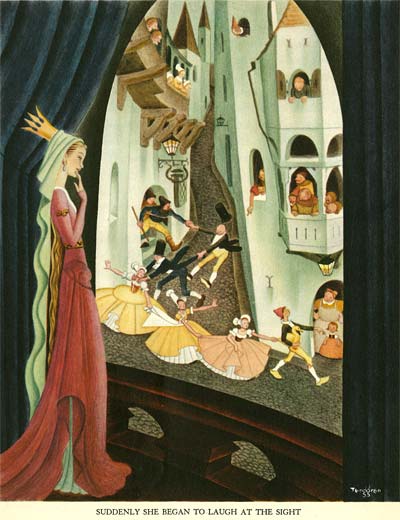

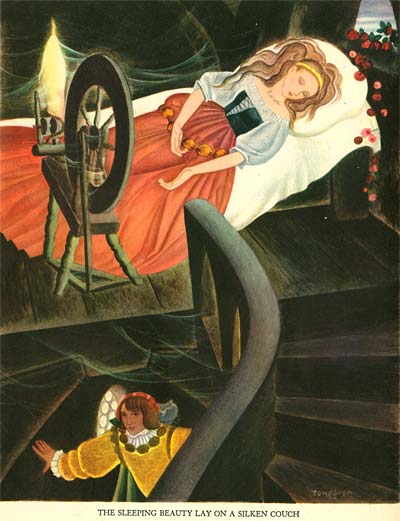

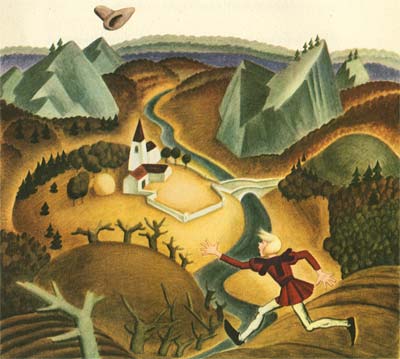

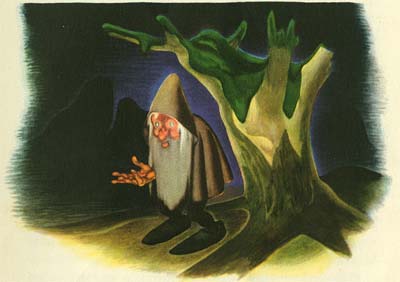

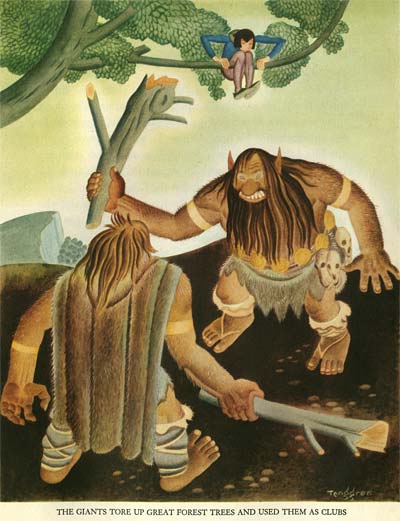

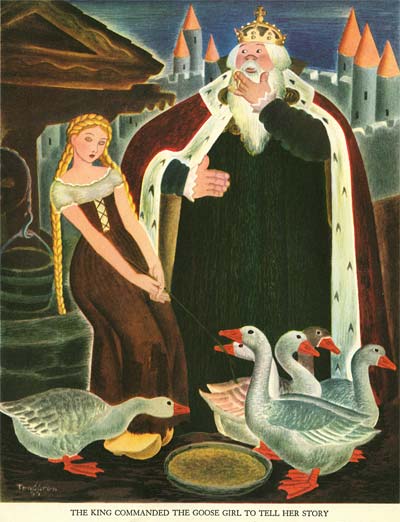

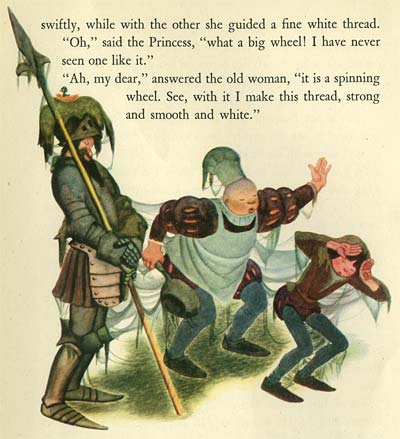

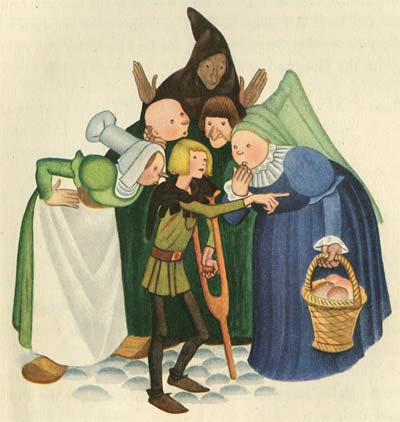

This particular book is amazing, because it shows Tenggen’s thought process and refinement gelling into what would become the classic "Golden Book style". (Click on the Three Little Pigs images above for a vivid example.) He simplifies by going back to his roots… combining the character designs of his mentor John Bauer with the colored pencil and watercolor style of his successor on the Bland Tomtar Och Troll series, Einar Norelius. It’s fascinating to compare this new streamlined style with the techniques of traditional golden age illustration. See how Tenggren has distilled the essence of the earlier attempts into a clear and simple presentation that still has plenty of beauty and balance.

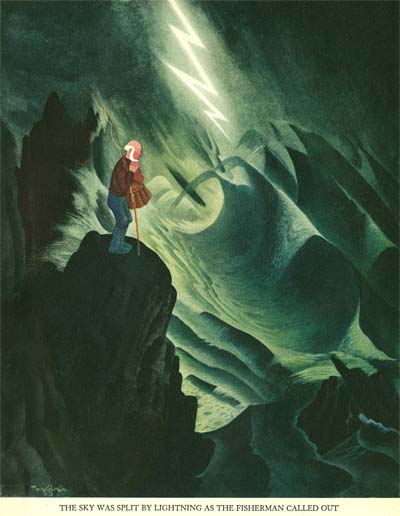

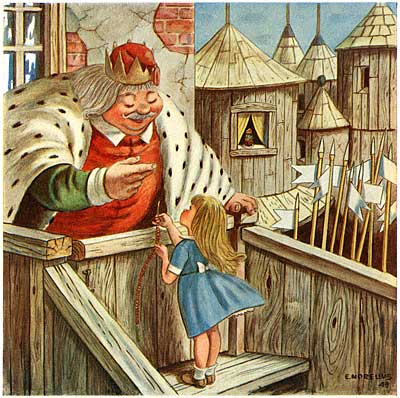

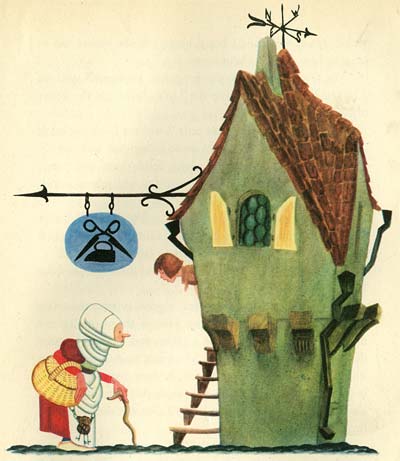

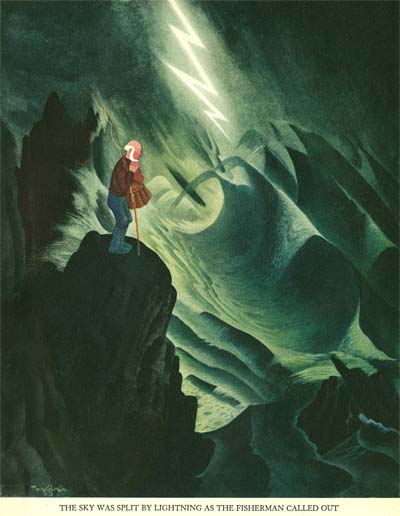

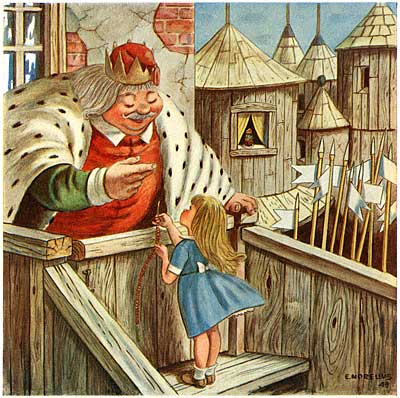

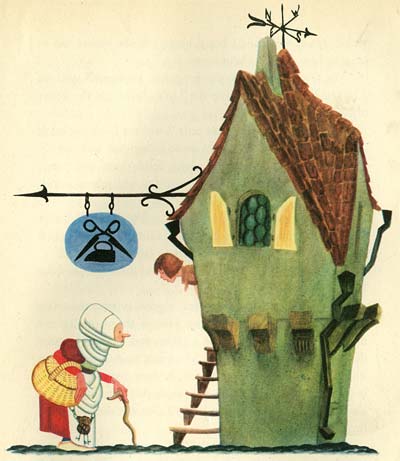

For inspiration, Tenggen goes all the way back to his roots… the work of his mentor, John Bauer. Here is one of Tenggren’s illustrations…

And here is one by Bauer from the Swedish Christmas annual, Bland Tomtar Och Troll…

He also appears to be familiar with the work of his successor on the Bland Tomtar Och Troll series, Einar Norelius. Here is Tenggren…

And here is Norelius…

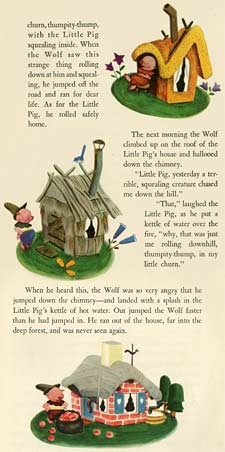

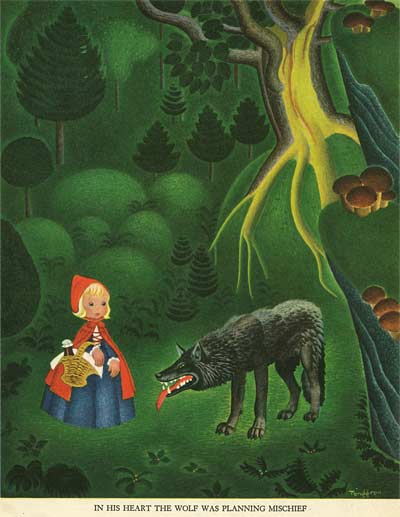

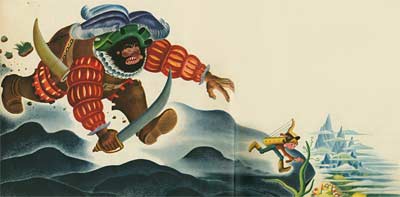

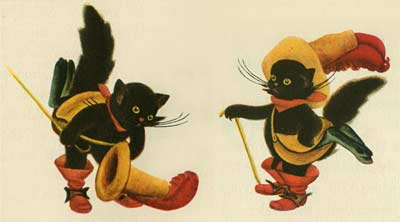

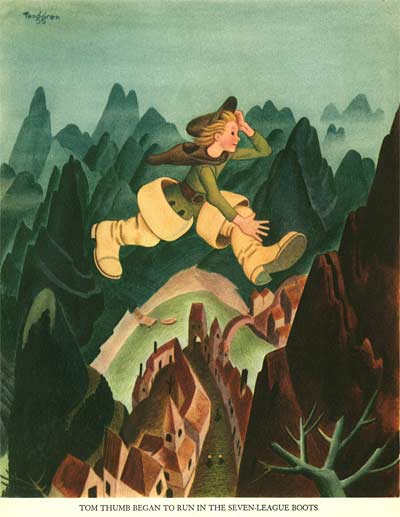

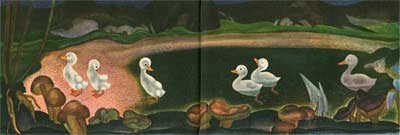

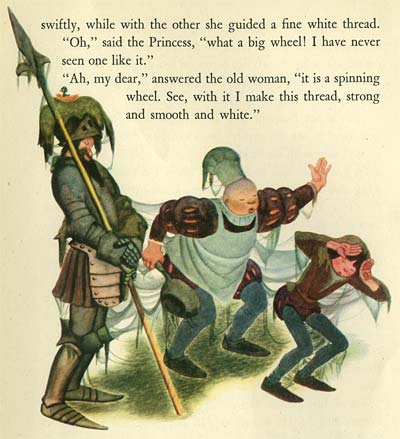

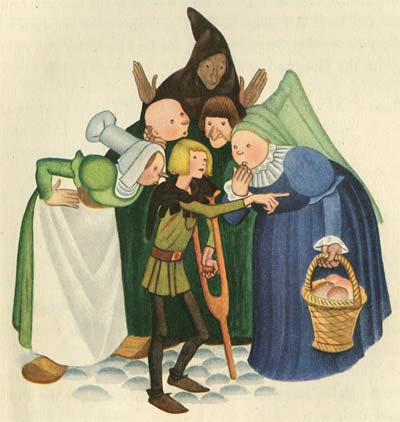

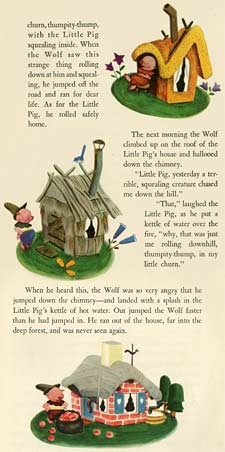

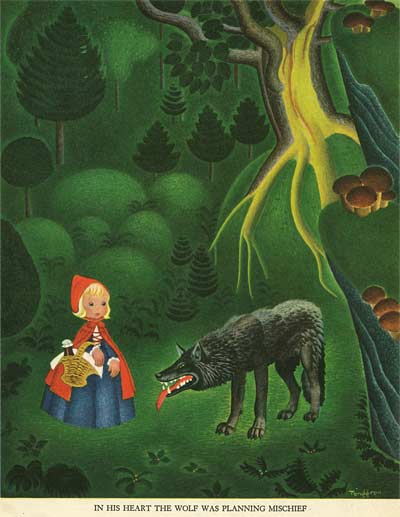

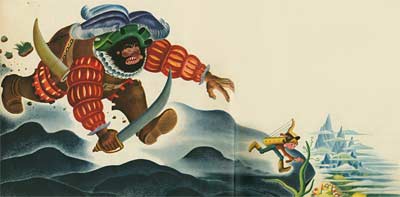

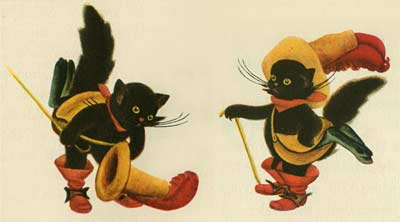

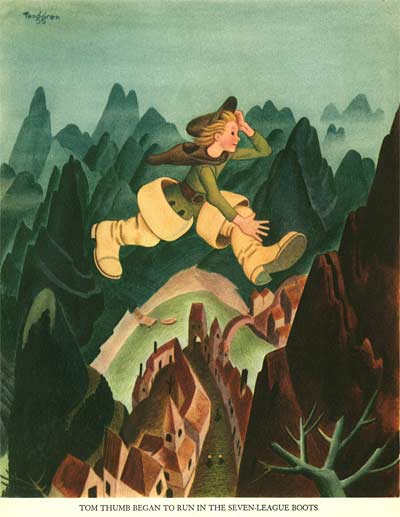

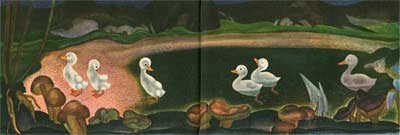

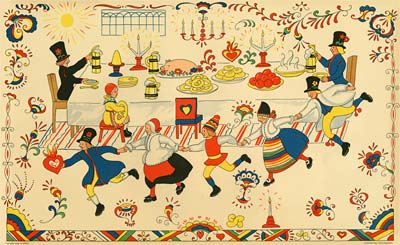

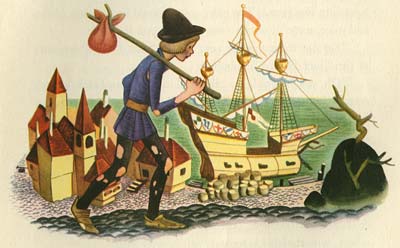

But halfway through Tenggren’s Tell It Again Book comes a huge breakthrough in design. Instead of the full page plates, Tenggren begins to float his characters over the white of the page, wrapping the text around the compositions. Background elements are reduced to small islands on the page, rather than extending out to the edges of a square bounding box. When I first got this book, I wondered why Tenggren had changed format halfway through. Clearly one reason was to save time and streamline the work of producing so many illustrations for a single book. But there was an aesthetic precedent to it as well. The answer has been hanging on my bedroom wall since I was a little boy!

But halfway through Tenggren’s Tell It Again Book comes a huge breakthrough in design. Instead of the full page plates, Tenggren begins to float his characters over the white of the page, wrapping the text around the compositions. Background elements are reduced to small islands on the page, rather than extending out to the edges of a square bounding box. When I first got this book, I wondered why Tenggren had changed format halfway through. Clearly one reason was to save time and streamline the work of producing so many illustrations for a single book. But there was an aesthetic precedent to it as well. The answer has been hanging on my bedroom wall since I was a little boy!

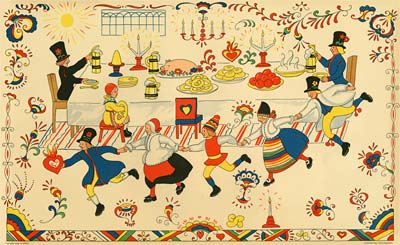

Like Tenggren, my Grandmother was Swedish. In the early 1920s, she took my father to Sweden to visit his Grandparents. It was the only time he was able to meet them, since he lived in Peterborough, Canada, a very long sea voyage away from their farm in Goteborg, Sweden. My great grandparents gave my father a gift to take home with him to remind him of the visit- this Swedish folk art picture…

When I was born, my father gave it to me to hang in my bedroom, and it’s been there ever since. Notice the similarity between the forward pitched perspective, the staging of the characters in clear profile silhouettes, and the simple rendering of the figures over the white of the paper on this print and the Tenggren illustrations that follow…

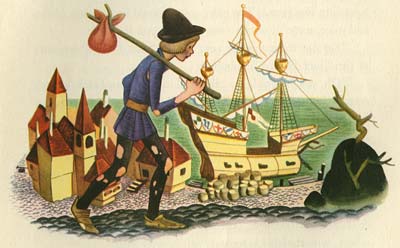

Tenggren had discovered a way to simplify and refine his illustrations even further. Instead of busy backgrounds full of details, he used just enough information to place the characters, and focused his attention on composing the figures. Immediately after publishing this book, Tenggren produced The Poky Little Puppy, the book that was the model for the hundreds of Little Golden Books that followed over the next seventy years. By going back to his roots and synthesizing his Swedish cultural upbringing, Tenggren invented a style that now seems to us to be quintessentially American.

Tenggren had discovered a way to simplify and refine his illustrations even further. Instead of busy backgrounds full of details, he used just enough information to place the characters, and focused his attention on composing the figures. Immediately after publishing this book, Tenggren produced The Poky Little Puppy, the book that was the model for the hundreds of Little Golden Books that followed over the next seventy years. By going back to his roots and synthesizing his Swedish cultural upbringing, Tenggren invented a style that now seems to us to be quintessentially American.

This is a perfect example of how immigrant artists of all kinds suited their artistic voice to their new lives in the United States in the first half of the 20th century. Carlo Vinci’s Italian heritage resulted in a superhero mouse who sang opera. Bill Tytla’s Eastern European roots helped him summon a devil in Fantasia. And Milt Gross’ Jewish upbringing expressed itself in comic celebrations of the ethnic vitality of New York City.

The melting pot of American culture sure is rich with cartoons!

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit spotlighting Illustration.

by

by

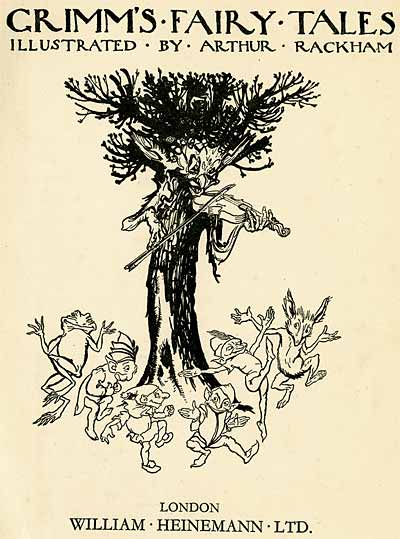

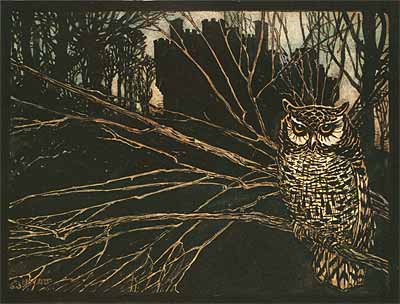

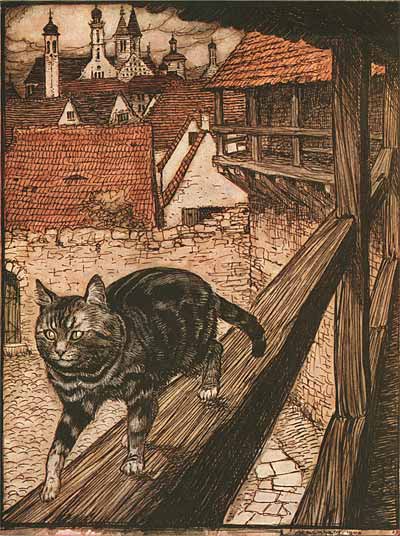

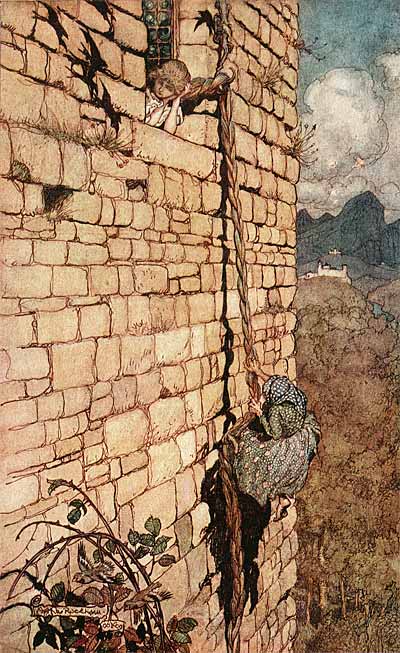

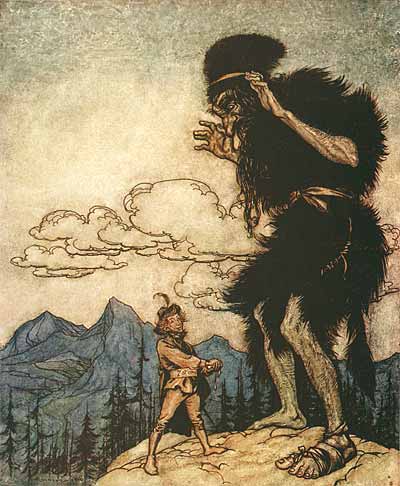

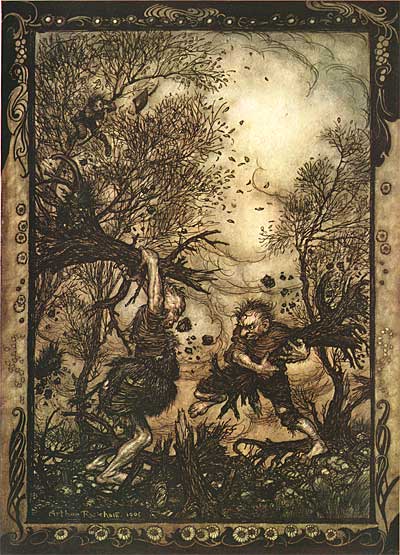

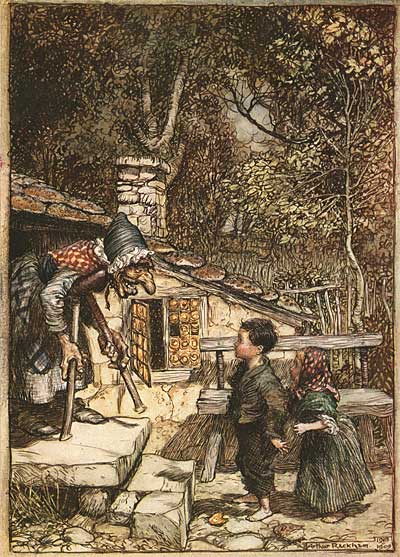

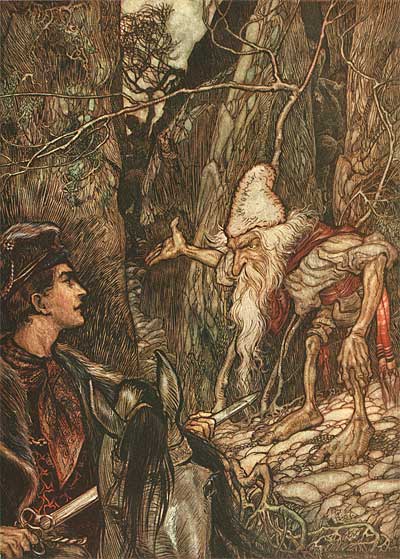

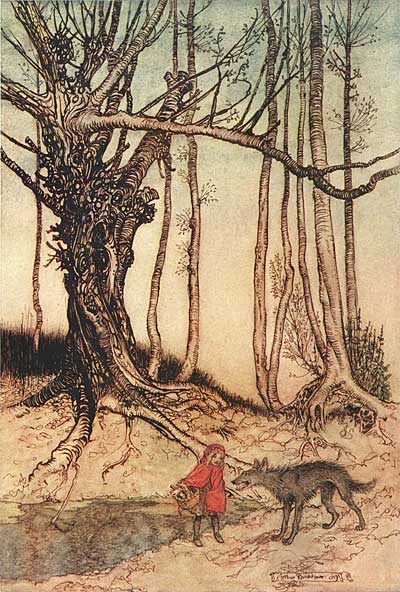

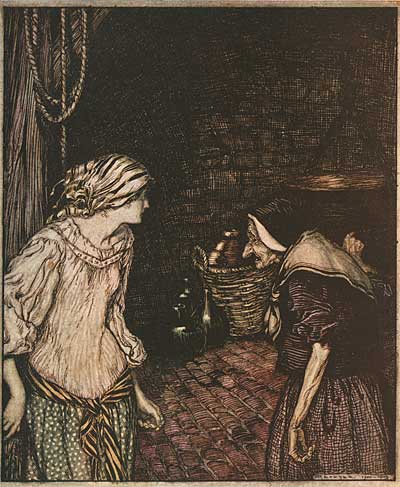

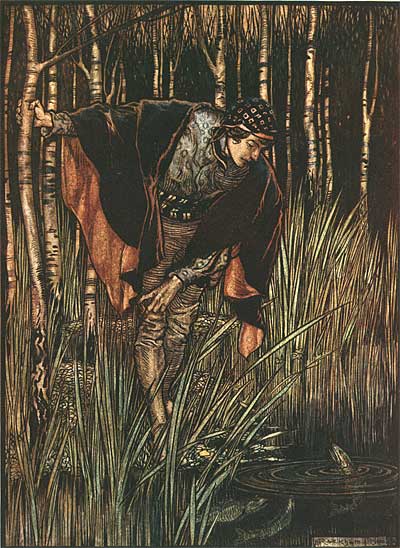

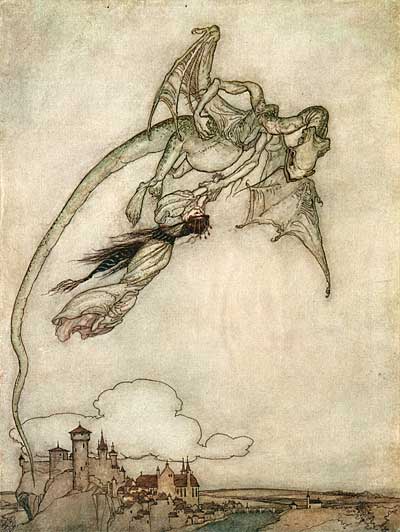

![]() Arthur Rackham is probably the single most influential children’s book illustrator. His delicate watercolors define the image of fairy tales in many people’s minds.

Arthur Rackham is probably the single most influential children’s book illustrator. His delicate watercolors define the image of fairy tales in many people’s minds.

![]() Walt Disney admired Rackham’s watercolor and pen & ink style, and instructed Gustaf Tenggren to work with Claude Coates and Sam Armstrong to adapt it for use in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Walt Disney admired Rackham’s watercolor and pen & ink style, and instructed Gustaf Tenggren to work with Claude Coates and Sam Armstrong to adapt it for use in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.