REFPACK055: December / January 2023-2024

REFPACK055: December / January 2023-2024

Click To View The Podcast On This RefPack

Every other month, Animation Resources shares a new Reference Pack with its members. They consist of e-books packed with high resolution scans video downloads of rare animated films set up for still frame study, as well as podcasts and documentaries— all designed to help you become a better artist. Make sure you download this Reference Pack before it’s updated. When it’s gone, it’s gone!

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

The latest Animation Resources Reference Pack has been uploaded to the server. Here’s a quick overview of what you’ll find when you log in to the members only page…

PDF E-BOOK:

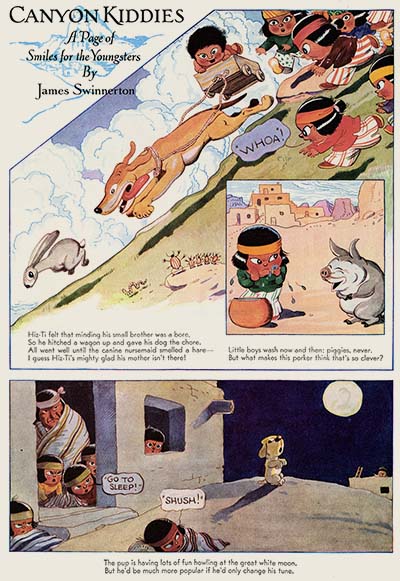

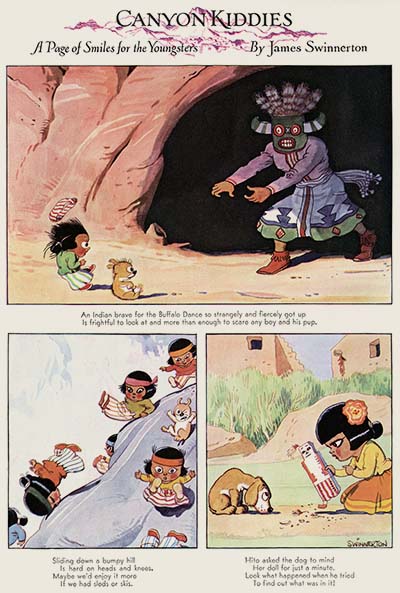

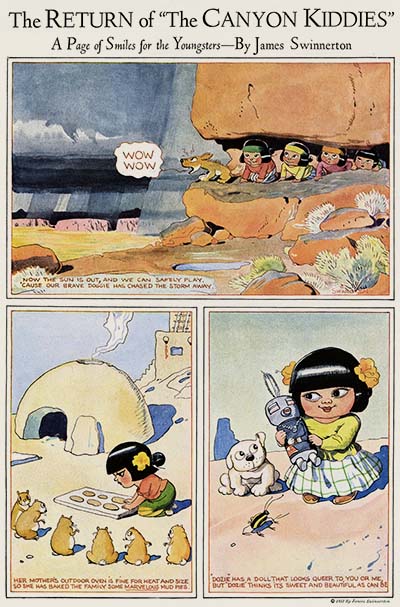

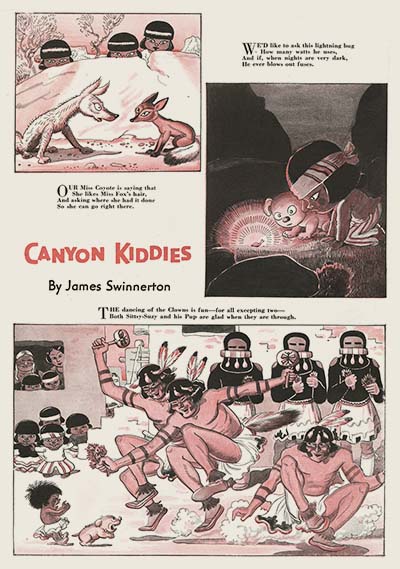

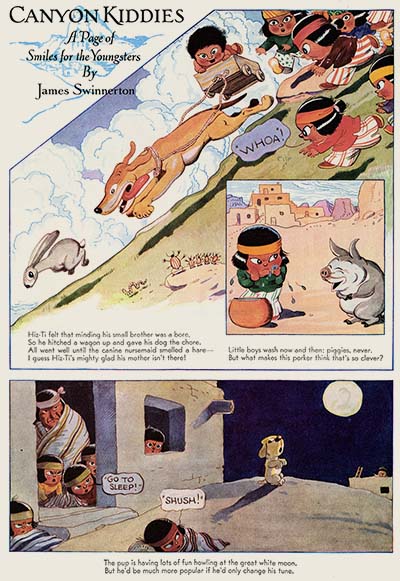

Jimmy Swinnerton’s Canyon Kiddies

Volume One

Download this article

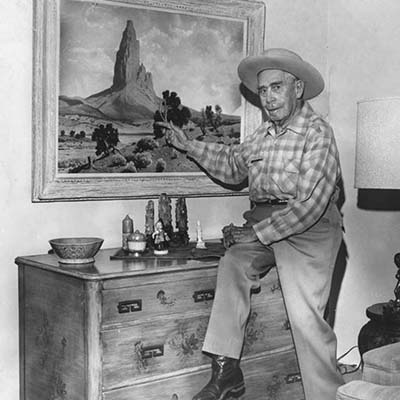

In 1907, Swinnerton was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was given two months to live. William Randolph Hearst was fond of him, and sent him West to Colton, California in hopes that the mild weather and dry air would help his illness. Swinnerton’s tuberculosis cleared up completely and he never left the West for the East coast again.

Traveling and living in Arizona, Swinnerton’s art began reflecting a Southwest desert landscape. He befriended Native American locals and treated them as peers. He was quoted as saying, "No one can become bigoted and narrow in the midst of broad desert vistas and great canyon walls." Good Housekeeping magazine hired him to produce full color single page stories about Native American children called Canyon Kiddies. Chuck Jones admired the comics and hired Swinnerton to work on an animated adaptation called "Mighty Hunters" in 1940.

SD VIDEO:

Two More Commercial Reels

Mid 1950s

Television commercials are so ubiquitous, we rarely give them a second thought. But a great deal of strategy goes into their creation. A commercial is designed to do three things… First, it must create a desire in the public’s mind for a particular product or service. Beautifully photographed scenes of steaming hot coffee being poured into cups; syrup dripping down the sides of buttered stacks of pancakes, pizzas being pulled out of ovens… all this is designed to get us salivating for the product. Secondly, an advertisement should build brand awareness and convince the audience that the sponsor’s product is better than that of the competitors. We are told that a product is “new and improved”, or it’s the brand doctors recommend, or studies show it’s 25% more effective against arthritis pain. Lastly, and this is often overlooked, a commercial is expected to engage and entertain the audience. Animated television commercials can inspire desire and build brand awareness as well as live action can, but it’s particularly effective at achieving that last goal.

Animation Resources has shared many commercial reels with its members in the past, and we’re happy to share two more courtesy of our Advisory Board member, Steve Stanchfield.

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

HD VIDEO:

The Legend Of The Forest (1st Mvt.)

Osamu Tezuka / Japan / 1987

Download this article

Throughout his life, Osamu Tezuka greatly admired Disney’s Fantasia, and aspired to make a film that synthesized classical music and animation in the same manner. He chose Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony Op. 36 as a soundtrack and set to work on animating his impressions of the music. Tezuka’s concept for "Legend Of The Forest" was to use the forest as a metaphor for the development of animation as a technique. The animation would mirror the step by step advancement of animation techniques from primitive animatics based on comics, like the early years of animation; and as the film progressed, the style would develop as animation developed, all the way to full animation. In the fourth movement, TV animation would invade the Disney style and drive it out, the way TV animation techniques replaced the labor intensive full animation of the 1940s and 50s.

Tezuka only completed the first and fourth movement before his death. We are sharing the first movement in this Reference Pack, and we will share the fourth one in the next.

SD VIDEO:

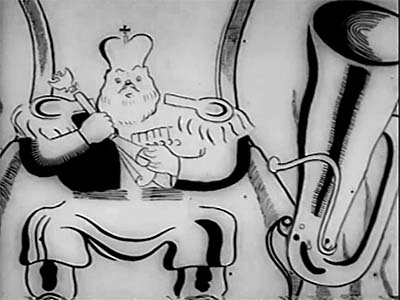

The Music Box

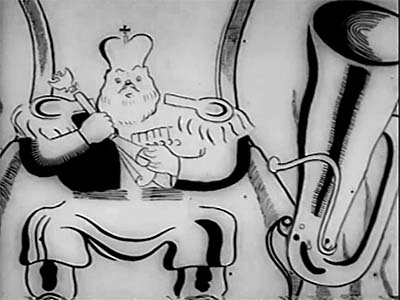

Nikolai Khodataev / Russia / 1933

The state sponsored studio Mezhrabpomfilm, employed most of the animators in Russia at that time, but Nikolai Khodataev was an exception. As an independent animator, he could come up with his own stories without the interference of government censors. "The Music Box" was more primitive technically than the state sponsored films, but creatively it was much more daring. The designs were by Daniel Cherkes and were highly stylized with a sinuous inked line, not unlike the drawings in contemporary caricature journals and avant-garde posters. The film was quite different than anything being made at that time, but ultimately that difference led to its downfall.

A year after "The Music Box" was released, Stalin declared that Socialist Realism was the only artistic movement that would be allowed, and the work of Khodataev was suppressed. While other artists sublimated themselves to Stalin’s decree, Khodataev chose to abandon his work in animation, feeling that it was better to have no art at all than to be limited to Socialist Realism. Other animators, principally Ivan Ivanov-Vano, carried the torch at the government controlled studios, and Soyuzmultfilm was founded in 1936.

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

SD VIDEO:

SD VIDEO:

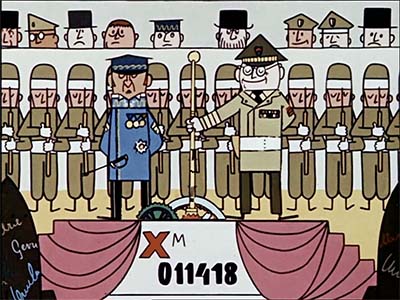

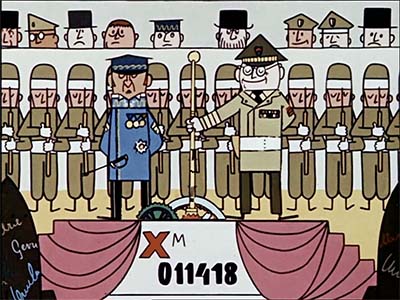

Sensation Of The Century

Otto Sacher / DEFA / East Germany / 1959

Otto Sacher was born in 1928 and studied at the Institute for Artistic Design in Halle, East Germany. In 1955, he founded the Animation department of the DEFA Studios, the state-owned film studio of the German Democratic Republic. DEFA was created in 1946 by the Soviets in the hopes that film was the best means to counter over a decade of Nazi propaganda. The style of DEFA was known as “Socialist Realism”, an ideologically focused kind of film that was tightly controlled by Soviet censors.

Strangely enough, DEFA was known for producing Westerns, but ones where the Indians were the “good guys” and the cowboys were the “bad guys”. The intent was to make the United States appear to be evil. In the mid 1950s, the studio began producing satirical films, and animation was the perfect medium for this. "Sensation Of The Century" is one of the earliest examples.

SD VIDEO:

Kaibutsukun & Gutsy Frog

Episodes 21 & 32 / 1969

Download this article

Kaibutsu-Kun is a horror-comedy series which follows a boy named Tarou Kaibutsu. He is accompanied by his monster friends Dracula, Wolfman and Franken. He also has a human friend named Hiroshi. Throughout the series they encounter all kinds of monsters, and in many cases are put at odds with them. The series was created by Fujiko Fujio, best known for his creation Doraemon. Production alternated between Tokyo Movie (known today as TMS Entertainment) and Studio Zero. It aired from April 21st, 1968 to March 23rd, 1969.

Gutsy Frog (known as Dokonjo Gaeru in Japanese) is a comedy series created by Yasumi Yoshizawa. It also happens to feature a boy by the name Hiroshi, who mistakenly fell on a frog (Pyonkichi). The frog sticks to his shirt and becomes his companion. The series was produced by Tokyo Movie Shinsha and ran from October 7th, 1972 to September 28th 1974, spanning over one hundred episodes.

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

HD VIDEO:

Bernini

Francesco Invernizi / Galleria Borghese / 2018

Download this article

Animators are called upon to animate the human figure in motion. They need to know how the body flexes and contracts, they have to be able to turn the masses in three dimensions, and they need to be able to convey personality through posing and gesture. There is no better way to develop these skills than figure drawing.

The nicest thing about drawing from sculpture is that the model is more patient and doesn’t get tired of holding a pose. The student has all the time he needs to capture all the planes and masses that make up the human figure. But it has to be a very special kind of sculpture to directly relate to live human models. Gian Lorenzo Bernini is one of the greatest sculptors for this purpose. His knowledge of musculature and skeletal structure is encyclopedic. His figures exude life and energy from all angles and all distances. A lifetime could be spent studying his work. Animation is a competitive field, and the best way to gain the edge and remain employed is to work on your figure drawing chops. I hope this documentary inspires you to do that.

HD VIDEO:

Hair And Fur

Curated By David Eisman

Download this article

While hand articulation may be the most technically challenging of all the principles, hair and fur simulation is perhaps the most tedious. The reasons behind such tedium are multifaceted. There is, of course, the difficulty involved with tracking each individual strand of hair or fray of fur. The more realistic the animator wishes the hair or fur to be, the more individual lines required. Thus, with each additional line, the difficulty of tracking increases exponentially. Additionally, the animator must juggle the movement of the individual strands versus the mass as a whole. If the movement of each strand is uniform and identical, the flow of the hair or fur will feel stale and lifeless. However, if the animator fails to coordinate the individual movements of the strands, the flow and rhythm of the mass of hair will not coalesce, and the hair or fur will move like a chaotic jumble that the viewer will almost certainly not recognize. Moreover, both the individual strands and the group of strands must follow the wave principle.

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

ANNUAL MEMBER BONUS ARCHIVE

Available to Student and General Members

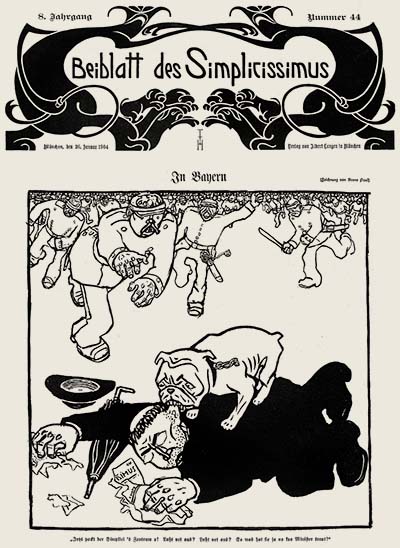

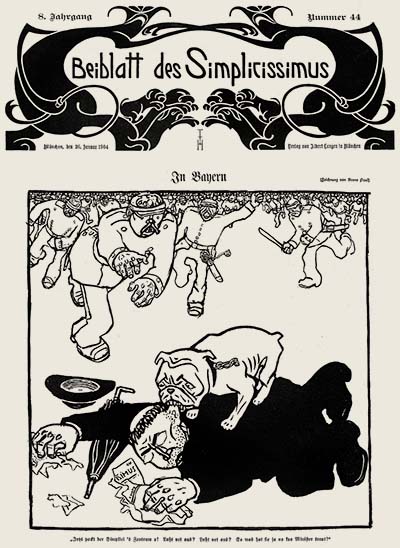

- EBOOK: Simplicissimus Vol. One December 1903-March 1904

- VIDEO: Astro Boy Pilot Tezuka 1963

- VIDEO: “Sno Fun” Terry / 1951

ANIMATION RESOURCES ANNUAL MEMBERS: Bonus Reference Pack 7 is now being rerun and is now available for download. It includes an e-book of the influential German caricature magazine, Simplicissimus, the pilot episode of Tezuka’s Astro Boy, and a Terry-Toon in HD featuring amazing animation by Jim Tier. These downloads will be available until January 1st and after that, they will be deleted from the server. So download them now!

If you are currently on a quarterly membership plan, consider upgrading to an annual membership to get access to our bonus page with even more downloads. If you still have time on you quarterly membership when you upgrade to an annual membership, email us at…

membership@animationresources.org

…and we will credit your membership with the additional time.

Click to access the…

Annual Member Bonus Archive

Downloads expire after October 1st, 2023

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Whew! That is an amazing collection of treasures! At Animation Resources, our Advisory Board includes great artists and animators like Ralph Bakshi, Will Finn, J.J. Sedelmaier and Sherm Cohen. They’ve let us know the things that they use in their own self study so we can share them with you. That’s experience you just can’t find anywhere else. The most important information isn’t what you already know… It’s the information you should know about, but don’t know yet. We bring that to you every other month.

Haven’t Joined Yet?

Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD A Sample RefPack!

Animation Resources is a 501(c)(3) non-profit arts organization dedicated to providing self study material to the worldwide animation community. If you are a creative person working in animation, cartooning or illustration, you owe it to yourself to be a member of Animation Resources.

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Animation Resources is one of the best kept secrets in the world of cartooning. Every month, we sponsor a program of interest to artists, and every other month, we share a book and up to an hour of rare animation with our members. If you are a creative person interested in the fields of animation, cartooning or illustration, you should be a member of Animation Resources!

It’s easy to join Animation Resources. Just click on this link and you can sign up right now online…

JOIN TODAY!

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

by

by

![]()

![]() Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.