The other day on Facebook, a few of my friends were discussing the impossibility of breaking down and analyzing humor. The answer to the question, “What is funny?” is a chimeral one. The second you pin it down, it dissolves into not being funny any more. However, one funny man was able to distill humor in words. Here is his article on the subject…

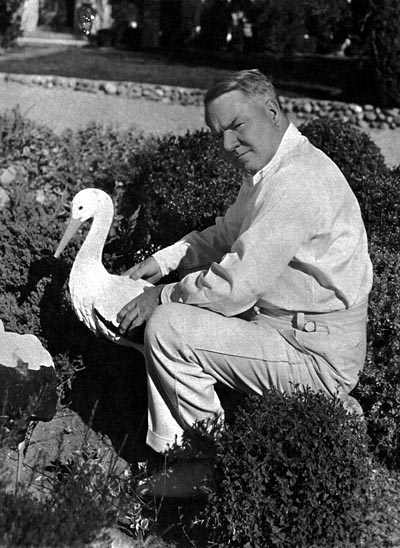

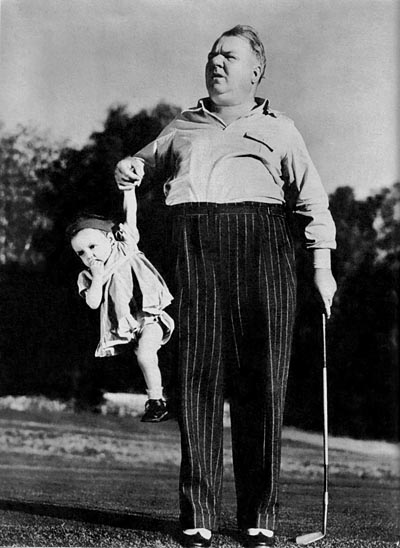

By W.C. Fields

I have spent years working out gags to make people laugh. With the patience of an old mariner making a ship in a bottle, I have been able to build situations that have turned out to be funny. But- to show you what a crazy way this is to make a living- the biggest laugh on the stage I ever got was an almost exact reproduction of an occurrence one evening when I was visiting a friend, and it took no thinking-up whatsoever.

At my friend’s home it didn’t even get a snicker, but in the theater, it caused the audience to yell for a full minute.

On the stage I was a pompous nobody. The telephone rang. I told my wife I would answer it in a manner that showed I doubted she was capable of handling an affair of such importance.

I said, “Hello, Elmer… Yes, Elmer… Is that so, Elmer?… Of course, Elmer… Good-bye, Elmer.”

I hung up the reciever and said to me wife as though I was disclosing a state secret, “That was Elmer.”

It was a roar. It took ten or twelve performances to find that “Elmer” is the funniest name for a man. I tried them all- Charley, Clarence, Oscar, Archibald, Luke, and dozens of others- but Elmer was tops. That was several years ago, Elmer is still funny- unless your name happens to be Elmer. In that case, you probably will vote for Clarence.

I don’t know why the scene turned out to be so terribly funny. The funniest thing about comedy is that you never know why people laugh. I know what makes them laugh, but trying to get your hands on the why of it is like trying to pick an eel out of a tub of water.

“Charley Bogle” spoken slowly and solemnly with a very long “o” is a laugh. “George Beebe” is not funny, but “Doctor Beebe” is. The expression, “You big Swede.” is not good for a laugh, but “You big Polack” goes big. But if you say “You big Polack.” in a show you’ll be visited by indignant delegations of protesting Poles. The Swedes don’t seem to mind.

Usually, towns that have a “ville” on the end of the name- like Jonesville- are not to be taken seriously, while those with “Saint” cannot be joked about. But will you tell me why St. Louis goes well in a gag and Louisville does not?

It’s difficult to put over a joke about any of the Southern states. They go best in sentimental songs. Northern states are different. A fellow from New Jersey, Iowa, Kansas or Minnesota can be funny (except to natives of those states.)

I don’t know the why of all this- any more than I know why a man gets sore if he slips and falls, while if a woman falls, she laughs. Nor why it is harder to put over comedy in Kansas City than in any other city in the United States, and easier in New York.

Flo Ziegfield never thought a comedy act was any good unless there was a beautiful girl in it, and he picked on me when I was doing my golf game in the Follies.

It was a scene in which I came on the golf course with a caddy and had trouble for eighteen minutes without ever hitting the ball. Lionel Barrymore told me it was the funniest gag he ever saw- and you can’t laugh off a testimonial like that!

One day Ziegfeld saw a picture in a paper showing a society girl with a Russian wolfhound. He dropped the paper, ran out, bought a wolfhound, and told me he was going to have Delores, one of his glorified girls, walk across the stage leading the hound, in the middle of my act!

I squawked, but it didn’t do any good, and at the next performance, just as I was building up laughs by stepping in a pie somebody had left on the golf course, out of the wings- for no reason except that Ziegfeld had told her to do it- comes Delores, with slow, stately tread, leading the Russian wolfhound.

I lost my audience instantly. They didn’t know what it was all about. I wasn’t going to give up my scene without a fight, so I looked at Delores in amazement, and then at the audience as if I, too were shocked at this strange sight on the golf course. When she was halfway across the stage, I said, “That’s a very beautiful horse.”

It got a big laugh.

Delores was so indignant because I had spoiled her parade, that she grabbed the hound around the shoulders and ran off the stage with him in her arms- and that was another laugh.

Ziegfeld and Delores raised the very devil. I maintained that I had improved the scene. They said I had ruined it, and finally we compromised. I was to let her have her moment and was not to speak the line until she was one step from her exit. It turned out that the suspense made it all the better.

I experimented night after night to find out what animal was the funniest. I finally settled upon “That’s a very beautiful camel.”

Usually there is nothing funny about horses- except prop horses with two men inside- but one of Ed Wynn’s best gags was where he sat down in a restaurant and said, “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse.” and the waiter went out and led in a live horse.

You usually can’t get a laugh out of damaging anything valuable. When you kick a silk hat, it must be dilapidated, when you wreck a car, bang it up a little before you bring it into the scene.

Yet Harold Lloyd had a great gag when he drove out proudly in a new, expensive car which immediately was commandeered by police, chasing bandits. The car was shot full of holes, and then it stalled on a railroad track. Lloyd jumped out and tried to start it, a train came along and hit it, and all he had left was the starting crank which he held in his hand.

It is funnier to bend things than to break them- bend the fenders on a car in a comedy wreck, don’t tear them off. In my golf game, which I have been doing for years, at first I swung at the ball and broke the club. Now I bend it at a right angle. If one comedian hits another over the head with a crowbar, the crowbar should bend, not break. In legitimate drama, the hero breaks his sword, and it is dramatic. In comedy, the sword bends, and stays bent.

There is something funny about mice and for years, without success, I tried to get a good gag about them. An accident finally gave it to me.

In Poppy, I was a small-time confidence man whose philosophy, you may remember, was “Never give a sucker an even break.” In one scene I was alone in a dark library, hunting on tiptoe for cards that I intended to mark, so that later I could cheat in a poker game. One night, as I was tiptoeing around the stage, being careful not to wake up anybody in the house, somebody, off-stage, accidentally knocked over a pile of boxes with a crash that shook the theater.

My scene was ruined for the moment. I had an inspiration. I stole down to the footlights and whispered across to the audience, “Mice!”

We kept that in the act too.

Professors of humor will tell you that the audienuce must not be allowed to guess what is coming, that humor is always based upon surprise. The theory is often true, but in You’re Telling Me, my most recent moving picture, I have a scene in which the laugh depends upon the fact that the audience knows in advance exactly what is going to happen.

I play a stupid and self-important inventor and I explain the details of my new burglar trap. According to my plan, I shall become friendly with the burglar, invite him in to sit down and talk things over, and, when he sits in a chair, a lever will automatically release an enormous iron ball which will hit him Socko! on the bean and kill him instantly.

From that moment the audience knows what’s coming- that pretty soon I’ll forget about the iron ball and will sit in the chair myself. The laughter begins when I start toward the chair. It reaches its peak before the ball whams me on the bean.

If I sat in a chair and the ball fell on my head, and then it was explained that it was a burglar alarm, the scene would fall flat.

The success of the scene depends upon the absence of surprise.

I know we laugh at the troubles of others, provided those troubles are not too serious. Out of that observation, I have reached a conclusion which may be of some comfort to those accused of “having no sense of humor.” These folks are charming, lovable, philanthropic people, and invariably I like them- as long as they keep out of the theaters where I am playing, which they usually do. If they get in by mistake, they leave early.

The reason they don’t laugh at most gags is that their first emotional reaction is to feel sorry for people instead of to laugh at them.

I like, in an audience, the fellow who roars continually at the troubles of the character I am portraying on the stage, but he probably has a mean streak in him, and, if I needed ten dollars, he’d be the last person I’d call upon. I’d go first to the old lady and old gentleman back in Row S who keep wondering what there is to laugh at.

W.C. Fields

September, 1934

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit entitled Theory.

THIS IS JUST THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG!

Animation Resources has been sharing treasures from the Animation Archive with its members for over a decade. Every other month, our members get access to a downloadable Reference Pack, full of information, inspiration and animation. The RefPacks consist of e-books jam packed with high resolution scans of great art, still framable animated films from around the world, documentaries, podcasts, seminars and MORE! The best part is that all of this material has been selected and curated by our Board of professionals to aid you in your self study. Our goal is to help you be a greater artist. Why wouldn’t you want to be a member of a group like that?

Membership comes in three levels. General Members get access to a bi-monthly Reference Pack as well as a Bonus RefPack from past offerings in the in-between months. We offer a discounted Student Membership for full time students and educators. And if you want to try out being a member, there is a Quarterly Membership that runs for three months.

JOIN TODAY!

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

FREE SAMPLES!

Not Convinced Yet? Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month! That’s 560 pages of great high resolution images and nearly an hour of rare animation available to everyone to download for FREE! https://animationresources.org/join-us-sample-reference-pack/

![]()

![]() Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.