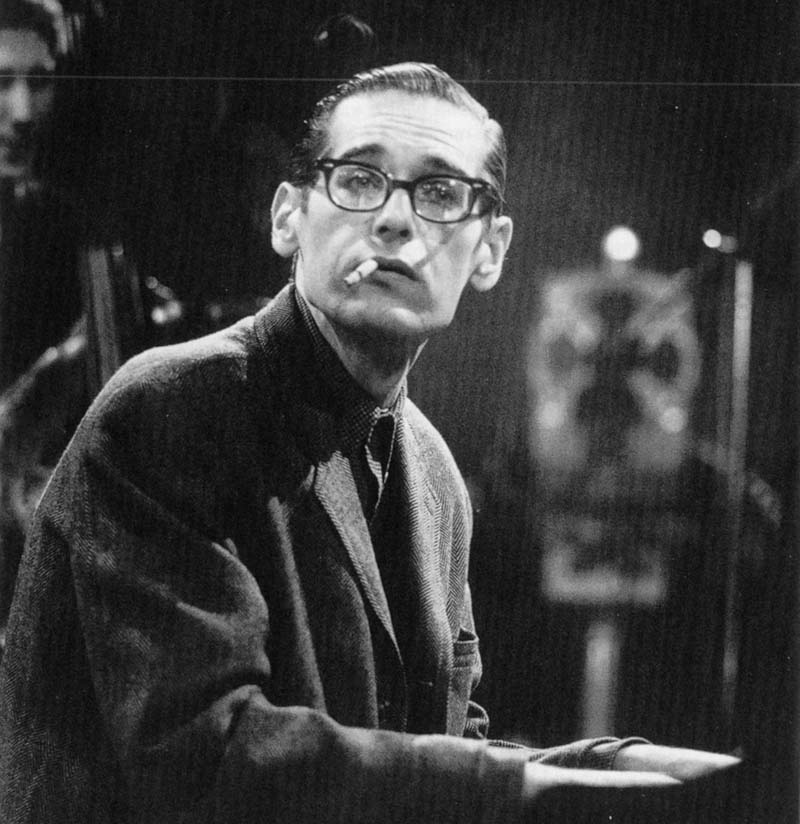

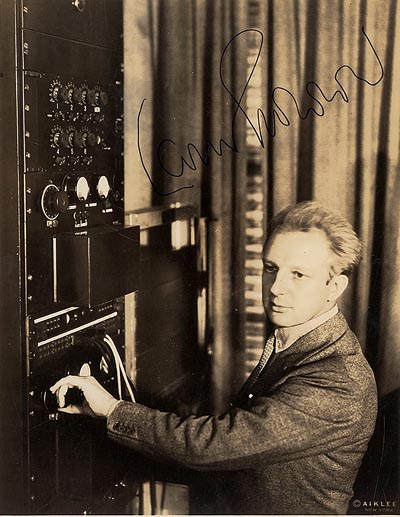

It isn’t often that a drop-dead genius sits down to speak directly to students. It’s even rarer for these special events to be recorded for television. My musical pal, Skip Heller tipped me off to a real treasure… a TV program from 1966 titled, "The Universal Mind of Bill Evans".

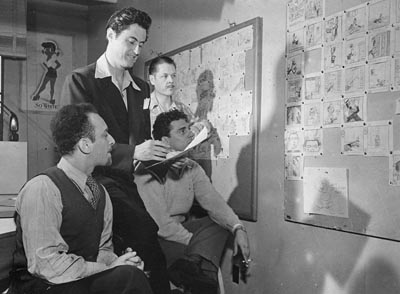

I’m a big believer in interdisciplinary study. An artist is an artist, and an animator can learn an awful lot from musicians, actors, dancers and performers in all of the other fields of creative endeavor. Here, we have the opportunity to learn from one of the giants of Jazz, pianist Bill Evans.

Evans was normally a quiet sort of person, and didn’t speak a lot about his work. But he had studied to be a teacher, and his brother who was also a teacher convinced him to sit down and address the fundamental principles of his work. As I first listened to this interview, I was amazed to hear many of the same theories I had heard from the great artists I have had the opportunity to work with in animation. I’ve broken the video into four YouTube movies, and I will make note of the most important quotes below each segment.

I believe that all people are in possession of what might be called a “universal mind”. Any true music speaks with this universal mind to the universal mind in all people. The understanding that results will vary only insofar as people have or have not been conditioned to the various styles of music in which the universal mind speaks. Consequently, often some effort and exposure is necessary in order to understand some of the music coming from a different period or a different culture than to which the listener has become conditioned.

Bill Evans argues that style, for better or for worse, eventually comes of itself- out of that mysterious interior well of creative inspiration that nourishes everyone to one degree or another. It’s much more important, Evans feels, to master fundamentals both in theory- so you understand what you’re doing, and in active practice- developing one’s musical muscles… not just technical dexterity, but the brain connection. Developing that facility to the point where the subconscious mind can take over the basic mechanical task of playing thus freeing the conscious to concentrate on the spontaneous creative element that distinguishes the best Jazz- and the best in all human activity.

Jazz is the only form of art that America has created and given to the world… but I think it’s more of a revival in a different form than what went on in classical music before. In the 17th century there was a great deal of improvisation in Classical music, and because of the fact that there were no electrical recording techniques to permanize or to “catch” music and to record it, the music was written so that it could be permanized that way. Slowly but surely the writing of the music and the interpreters of the music gave way to more and more interpretation and more and more cerebral composition and less and less improvisation. So finally, improvisation became a lost art in Classical music and we have only the composer and the interpreter.

I feel that Jazz is not so much a style as it is a process of making music. It’s the process of making one minute’s music in one minute’s time. Whereas when you compose, you can make one minute’s music and take three months… We tend to think of Jazz as a stylistic medium, but we must remember that in an absolute sense, Jazz is more of a certain creative process of spontaneity than a style… Any good teacher of serious classical composition will always tell a student that the composition should sound as if it’s improvised. It should have a spontaneous quality, so actually, the art of music is the art of speaking with this spontaneous quality.

The person who succeeds in anything has the realistic viewpoint at the beginning in knowing that the problem is large and that he has to take it a step at a time and he has to enjoy this step by step learning procedure.

It’s better to do something simple that is real. It’s something you can build on. because you know what you’re doing. Whereas, if you try to approximate something very advanced and don’t know what you’re doing, you can’t build on it.

No matter how far I might diverge or find freedom in this format, it only is free insofar that it has reference to the strictness of the original form. That’s what gives it its strength.

The whole process of learning the facility of being able to play Jazz was to take these problems from the outer level in- one by one and to stay with it at a very intense conscious concentration level until that process becomes secondary and subconscious… Then you can begin concentrating on that next problem which will allow you to do a little bit more.

I don’t consider myself as talented as many people, but in some way that was an advantage. I didn’t have a great facility immediately. I had to be more analytical. It forced me to build something.

Most people just don’t realize the immensity of the problem and either, because they can’t conquer it immediately, think they don’t have the ability; or they’re so impatient to conquer it that they never do see it through.

I remember coming to New York to make or break in Jazz and saying to myself, “How do I attack this practical problem of becoming a Jazz musician- making a living and so on… Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that all I must do is takke care of the music- even if I do it in a closet. And if I really do that, somebody is going to come to the closet and open the door and say, “Hey, we’re looking for you!”

When you begin to teach Jazz, the most dangerous thing is you begin to teach style… If you’re going to try to teach Jazz, you must teach principles that are separate from style. You have to abstract the principles of musi which have nothing to do with style. This is exceptionally difficult.

Pretty amazing, isn’t it?!

Lest you think that Bill Evans’ ideas only apply to music, scan over those quotes up above and try to apply them to animation…

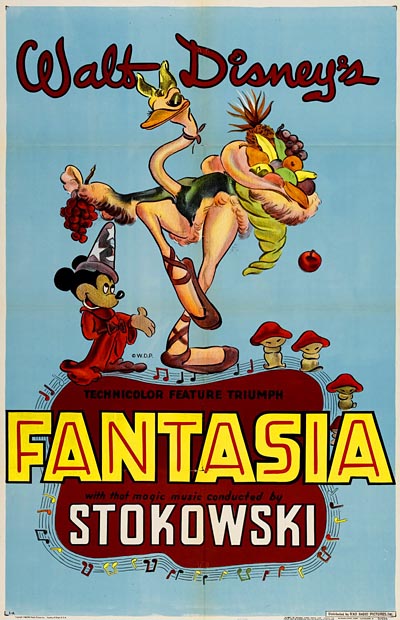

Animation in its purest form follows the rhythms of music and speaks to the same universal mind. Think of the funniest walk cycle you have ever seen and try to put it into words. You can’t. It doesn’t matter what language you speak. Great poses and pure movement speaks to our humanity- the part of us that operates below the verbal level.

The difference between acting for animation and acting on the stage is the difference between composition and real time improvisation. Yet the goal is the same… a feeling of spontaneity.

Deviation and exaggeration is best when it reflects the strictness of the form of the idea. Angles on characters for no reason other than to put angles on them, arbitrary exaggeration and deliberately wonky perspective don’t have the same strength as exaggeration based on the original form you’re depicting.

Style is something that comes from within after the abstract fundamentals are mastered and absorbed. If you try to learn to draw by learning a style- be it anime or Spumco or Disney- you are building upon a foundation that won’t support your artistic growth.

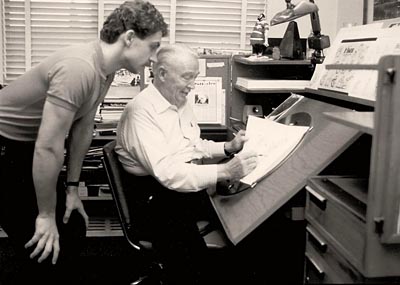

Learning to draw and animate is a huge undertaking and the way to do it is to break down, analyze and practice the principles one by one- from simple to more complex- just like the way the Preston Blair Course is organized. As you master the principles, they become second nature and you can move on to learning new principles.

It can be daunting to imagine how one is going to create a career in animation, but ultimately, one just has to serve the artform- even if there is no audience for your work yet. Eventually, if you serve the artform well, the audience will come.

Musicians are talking about this post.

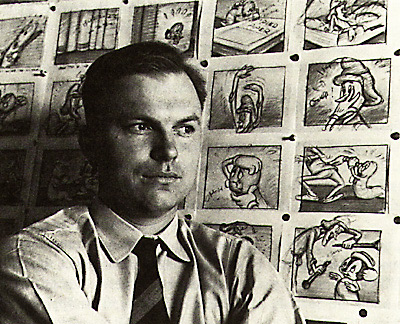

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit entitled Theory.

Back To School Days At Animation Resources

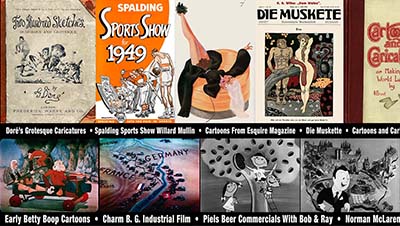

Fall is time to join Animation Resources as a student member. Annual dues for full time students and educators is discounted. It’s the biggest bargain in animation at only $70 a year. Animation School is great, but it doesn’t give you everything you need to become a professional animator. You need to invest in self-study to be successful in this highly competitive field. That’s exactly what Animation Resources can help you do if you become a member. Each day we’ll be highlighting more reasons why you should join Animation Resources. Bookmark us and check back every day.

There’s no better way to feed your creativity than to be a member of Animation Resources. Every other month, we share a Reference Pack that is chock full of downloadable e-books and still framable videos designed to expand your horizons and blow your mind, as well as educational podcasts and seminars. It’s easy to join. Just click on this link and you can sign up right now online.

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

FREE SAMPLES!![]()

Not Convinced Yet? Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

JOIN NOW! https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/