LAST CALL! RefPack048 will be replaced by RefPack049 soon. Download the current one while you can.

If you aren’t a member of Animation Resources yet, you can join today and download the current Reference Pack, and have a new one to download next week. JOIN Today! >https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

Every other month, Animation Resources shares a new Reference Pack with its members. They consist of e-books packed with high resolution scans video downloads of rare animated films set up for still frame study, as well as podcasts and documentaries— all designed to help you become a better artist. Make sure you download this Reference Pack before it’s updated. When it’s gone, it’s gone!

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

The latest Animation Resources Reference Pack has been uploaded to the server. Here’s a quick overview of what you’ll find when you log in to the members only page…

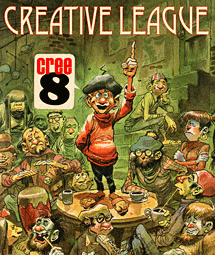

Irv Spector’s Coogy

![]()

1951-1952

Irv Spector was an animation story and layout artist who also worked in newspaper comics and comic books. Spector’s newspaper comic, Coogy is little known today, largely because of its limited distribution. This is a shame, because Coogy is an excellent comic, with brilliant compositions and great character posing and acting.

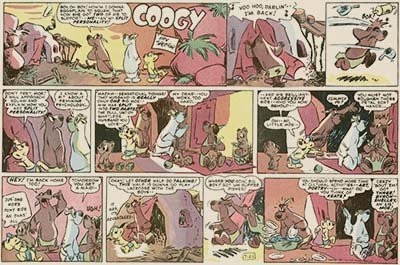

Two Cinemascope Cartoons

![]()

Grand Canyonscope 1954 / No Hunting 1955

Film makers often take aspect ratios for granted, because most films are made with standard formats— the Academy aspect (similar to old school television) or 1.85 1 (the current standard for HD TV and movies). However there have been exceptions to these standards over the years, and each aspect has its own pluses and minuses. In this RefPack, we talk about two rare cartoons filmed in Cinemascope.

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Two Fischerkoesen Shorts

![]()

Hans Fischerkoesen: Weathered Melody 1943 / The Snowman 1944 (Germany)

Hans Fischerkoesen was often referred to as "the Walt Disney of Germany". During the Nazi years, Hitler and Goebels ordered him to produce films that were technically the equal of those of the Disney Studios. The orders were backed by ample funding, and Fischerkoesen went to work on three animated films that would introduce the German animation industry to the world. We are sharing two of them in this RefPack.

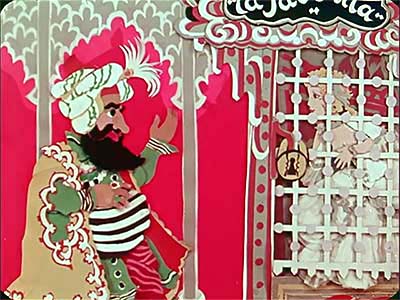

Cipollino: The Onion Boy

![]()

Boris Dyozhkin / Soyuzmultfilm, Russia / 1961

The story of Cipollino, the Onion Boy began as a fairy tale in an Italian children’s magazine, and became well known in Russia, leading to an animated featurette and an opera. In the 1930s, Boris Dyozhkin broke with other Soviet artists who rejected the Western style, studying Fleischer and Disney films frame by frame to break down the techniques being used. His study led him to an unique understanding of the synchronization of rhythm between music and motion, which made him one of the most sought after timing directors at Soyuzmultfilm.

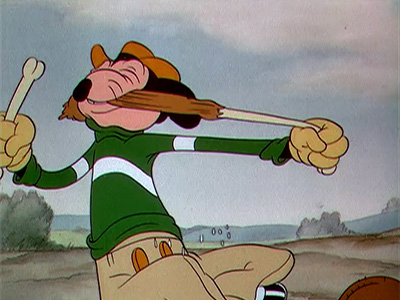

Well, Just You Wait Ep.05

![]()

Vyacheslav Kotyonochkin / Soyuzmultfilm, Russia / 1972

We continue the Russian series Nu, Pogodi! (Well, Just You Wait!) with episode 05, “City Streets: Metro”. In a 2014 poll of audiences all over Russia, Well, Just You Wait! was voted the most popular cartoon series of all time by a landslide. Although the series resembles both Tom & Jerry and the Roadrunner and Coyote series, the director, Kotyonochkin claimed not to have ever seen any of these Hollywood cartoons until 1987 when his son got a video tape recorder and Western tapes began to be imported.

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Six Maxi Cat Mini Cartoons

![]()

Zlatko Grgic / Zagreb Films, Croatia / 1971

Next up is a series of mini-cartoons from Zagreb. The animator and director of these mini-cartoons was Zlatko Grgic, a Croatian animator who later emigrated to Canada to join the Canadian Film Board. The cartoons are based on a simple premise or prop, and play off a simple sequence of gags building to a topper gag. There is no attempt at telling a story or conveying complex personality— just fun. They form a great model for students wanting to learn to animate.

Cat And Mouse

![]()

Wladyslaw Nehrebecki / Bielsko Biala Studio, Poland / 1958

Now we shift from Croatia to Poland. Clearly influenced by the films of UPA, "Cat And Mouse" skillfully juggles three of the fundamental elements of artistic rendering— line, shape and form. There’s a lot of fourth dimensional gags where one dimensional lines move alongside two dimensional flat shapes of color in three dimensional ways. This combines to create the best kind of cartoon magic.

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Hajime Ningen Gyatorz

![]()

Curated by JoJo Baptista

![]()

Ep.36 / Ep.44 (1975)

Animation Resources Board Member JoJo Baptista curates another pair of half hour episodes from Japan with First Human Giatrus, an anime series from 1974, based on the manga by Shunji Sonoyama. The series follows the misadventures of a cave dwelling family set in the stone age. The animation studio behind the anime (Tokyo Movie) did their best to keep his style intact. There’s a note in the style guide to not draw the characters volumetrically, but rather in Sonoyama’s flat style. Lots of funny designs are to be found in this series, along with some simple but effective staging as well.

Two Billy Bevan Keystone Comedies

![]()

“She Sighs By The Seaside” 1921

“Lizzies Of The Field” 1924

Billy Bevan was a skilled pantomimist, and an integral part of the Mack Sennett troupe of silent comics. Even though Keystone introduced many comics that would go on to become famous, they generally didn’t reach their peak of fame at Keystone. This was due to Sennett’s focus on funny situations, rather than funny characters in his films. As you study these shorts, you’ll want to pay attention to the staging and timing rather than subtle acting or story construction. There are some brilliant action sequences here.

Resistance

![]()

Curated By David Eisman

David Eisman shares some breakdown clips with us this time on the subject of resistance. Resistance, like weight, is a crucial technique in the animator’s toolkit. Knowledge of the different categories will allow the animator to craft poses and sequences that best create the effect that the audience will recognize as the correct type of resistance.

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Annual Member Bonus Archive

![]()

Available to Student and General Members

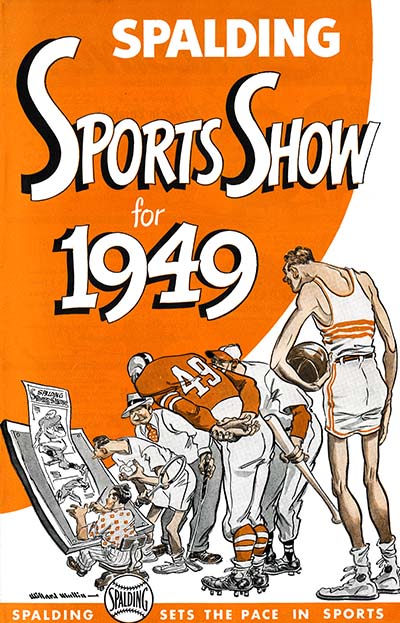

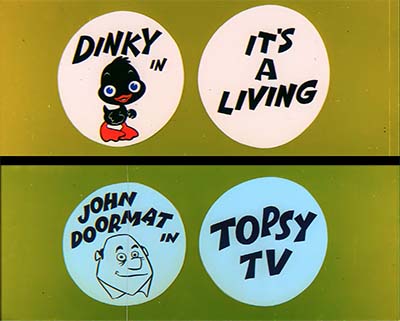

ANIMATION RESOURCES ANNUAL MEMBERS: Reference Pack 017 is now being rerun and is now available for download. It includes a PDF e-book of rare sports cartoons by Willard Mullin, two Cinemascope cartoons in their original aspect ratio (and high definition!) and a half hour of rare paper puppet films by Lotte Reiniger. These downloads will be available until December and after that, they will be deleted from the server. So download them now!

Click to access the…

Downloads expire after December 2022

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Whew! That is an amazing collection of treasures! At Animation Resources, our Advisory Board includes great artists and animators like Ralph Bakshi, Will Finn, J.J. Sedelmaier and Sherm Cohen. They’ve let us know the things that they use in their own self study so we can share them with you. That’s experience you just can’t find anywhere else. The most important information isn’t what you already know… It’s the information you should know about, but don’t know yet. We bring that to you every other month.

Haven’t Joined Yet?

Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD A Sample RefPack!

Animation Resources is a 501(c)(3) non-profit arts organization dedicated to providing self study material to the worldwide animation community. If you are a creative person working in animation, cartooning or illustration, you owe it to yourself to be a member of Animation Resources.

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Animation Resources is one of the best kept secrets in the world of cartooning. Every month, we sponsor a program of interest to artists, and every other month, we share a book and up to an hour of rare animation with our members. If you are a creative person interested in the fields of animation, cartooning or illustration, you should be a member of Animation Resources!

It’s easy to join Animation Resources. Just click on this link and you can sign up right now online…

JOIN TODAY!

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

![]()

![]() Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.