REFPACK 033

REFPACK 033

Members Only Download

Every other month, members of Animation Resources are given access to an exclusive Members Only Reference Pack. These downloadable files are high resolution e-books on a variety of educational subjects and rare cartoons from the collection of Animation Resources in DVD quality. Our current Reference Pack has just been released. If you are a member, click through the link to access the MEMBERS ONLY DOWNLOAD PAGE. If you aren’t a member yet, please JOIN ANIMATION RESOURCES. It’s well worth it.

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

PDF E-BOOK

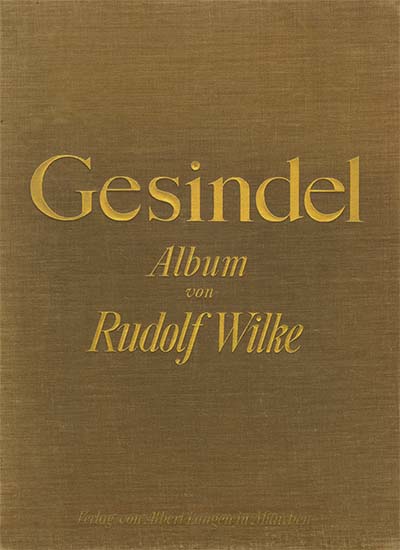

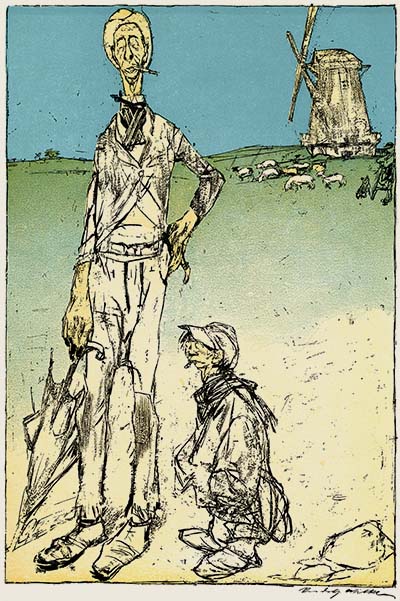

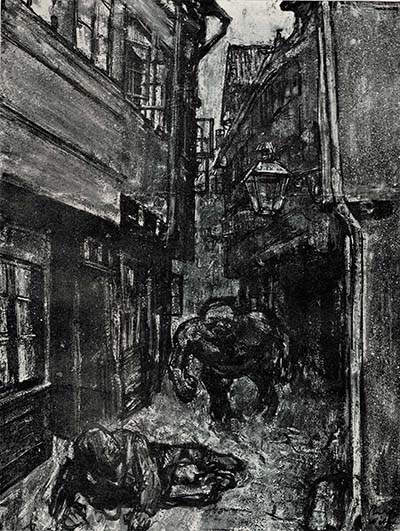

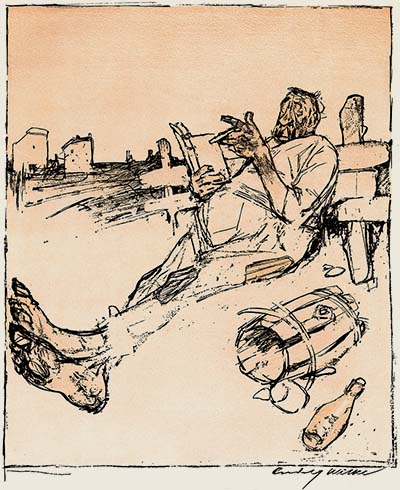

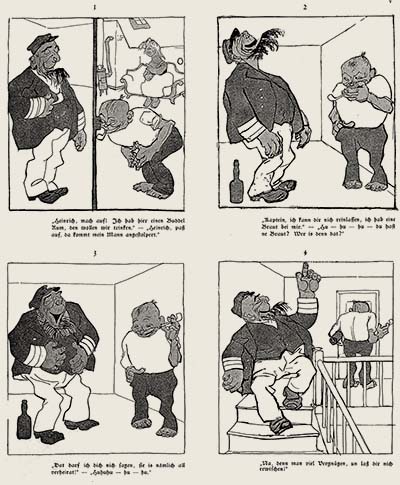

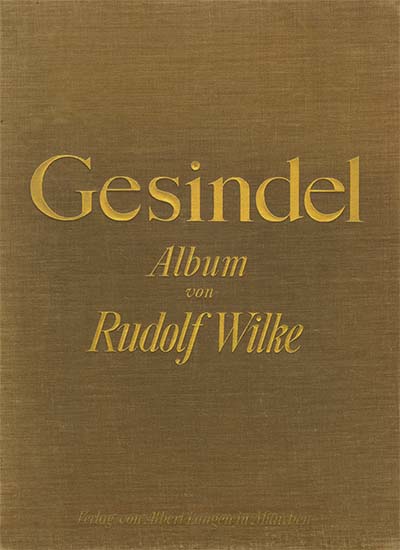

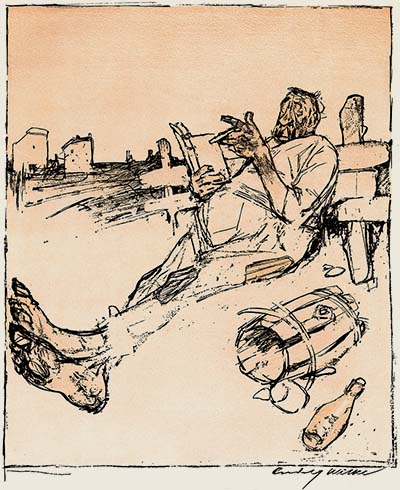

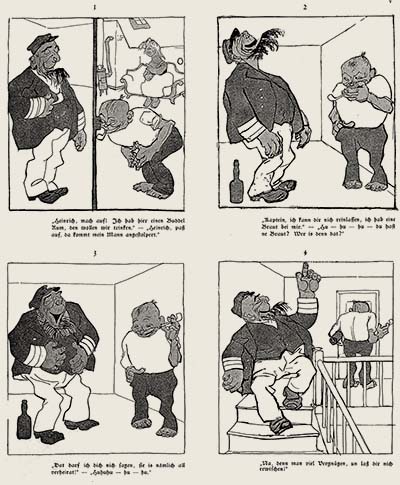

Rudolf Wilke

Gesindel “Riff-Raff” (1908)

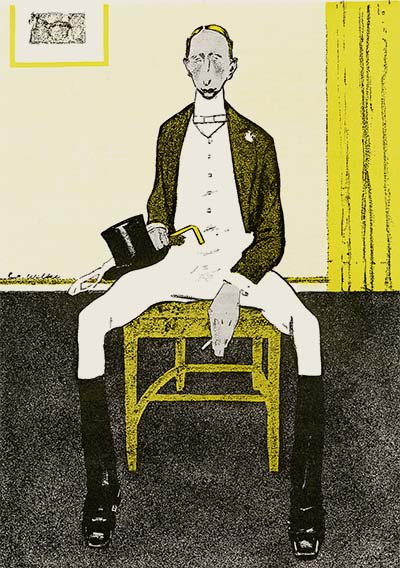

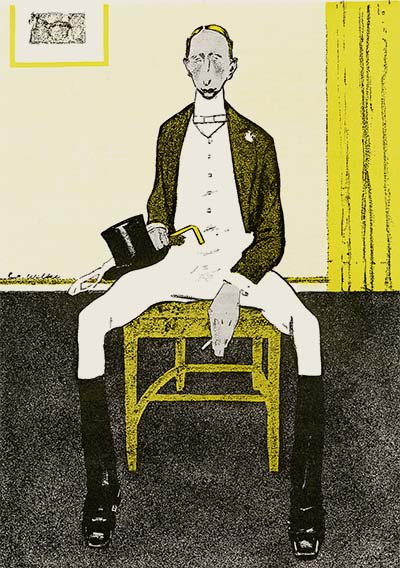

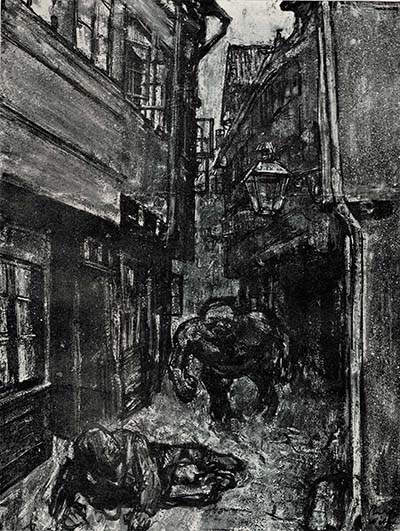

Rudolf Wilke was born in Braunschweig, Germany in 1873. He studied fine art in Munich and Paris, and later set up a studio with Bruno Paul, one of the founders of "Jugenstil". Paul was a regular contributor to Jugend magazine and brought Wilke in to work with him there. Albert Langen, the publisher of Simplicissimus saw Wilke’s in Jugend and recruited both him and Paul to join the staff in 1897. Their work in Simplicissimus won them both worldwide acclaim. Langen had originally envisioned the publication as a literary and illustrative magazine, but as time passed, the staff’s focus shifted to caricature and aggressive political satire.

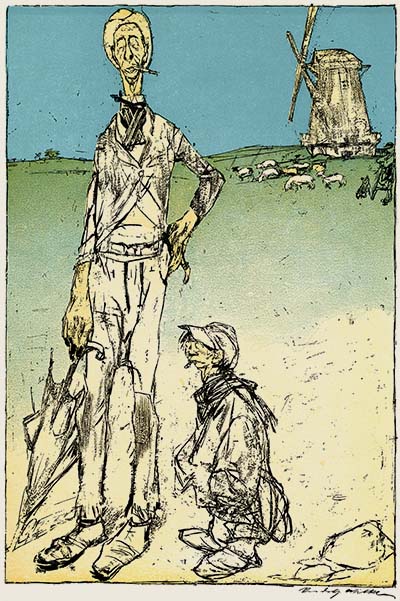

Along with artists Eduard Thöny and Ludwig Thoma, Wilke embarked on a trip to Marseilles, Algiers, Tunis, Naples and Rome in 1904. He honed his skills as a caricaturist on this trip, focusing on common people and the contrasts between classes. In 1906, the staff of Simplicissimus— Paul, Wilke, Thöny and Thoma, along with Thomas Theodore Heine, Olaf Gulbransson, and Ferdinand von Reznícek— petitioned Arthur Langen to convert Simplicissimus into a joint stock company, granting more editorial power to the staff. This shift in power envigorated the magazine. But just two years later, Wilke died unexpectedy; and the following year, artist Ferdinand von Reznícek also passed away. Their deaths were keenly felt at the magazine, and they were never replaced.

Even though he only lived to be 35 years old, Wilke has made a lasting impact on the world of cartooning. This portfolio of cartoons, titled “Gesindel” (which translates to “Riff-Raff”) was published as a memorial to Wilke upon his death. This collection represents some of his best work. Assistant Archivist, Megan Simon supervised the digitization, and Stephen Worth did the digital restoration work and layout. Hendrick Vham and Damian Christinger of the Weimar Era Facebook group kindly agreed to translate the captions and provide context to the cartoons. Many thanks to all of Animation Resources’ members and volunteers for making projects like this possible.

REFPACK034: Rudolf Wilke

Adobe PDF File / 48 Pages / 267 MB Download

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

Not A Member Yet? Want A Free Sample?

Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

by

by