Every other month, members of Animation Resources are given access to an exclusive Members Only Reference Pack. In September 2015, they were able to download Volume 3 of the classic Zim Cartooning Course. Our Reference Packs change every two months, so if you weren’t a member back then, you missed out on it. But you can still buy a copy of this great e-book in our E-Book and Video Store. Our downloadable PDF files are packed with high resolution images on a variety of educational subjects, and we also offer rare animated cartoons from the collection of Animation Resources as downloadable DVD quality video files. If you aren’t a member yet, please consider JOINING ANIMATION RESOURCES. It’s well worth it.

PDF E-BOOK:

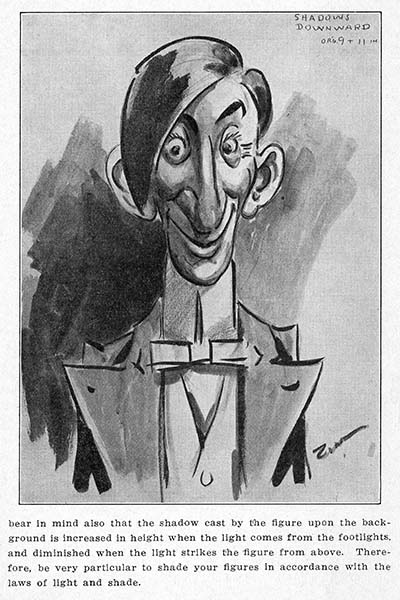

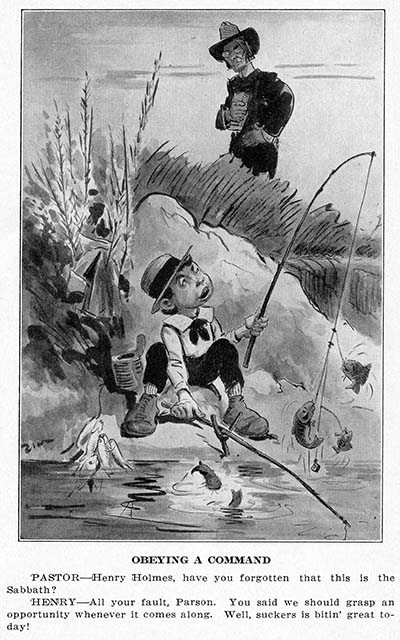

Eugene "Zim" Zimmerman![]()

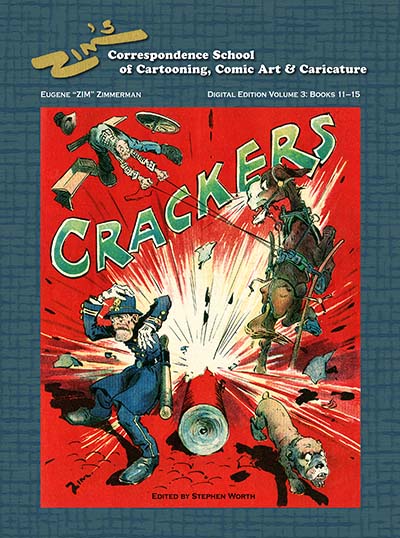

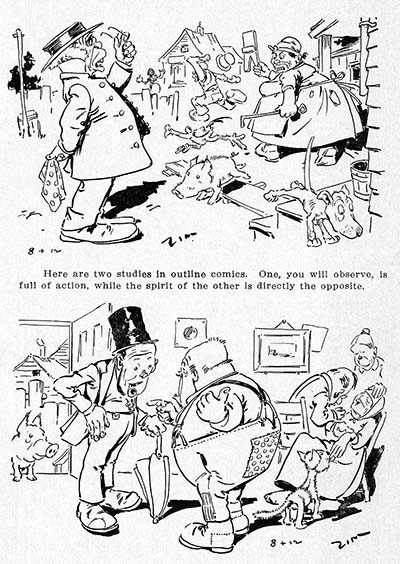

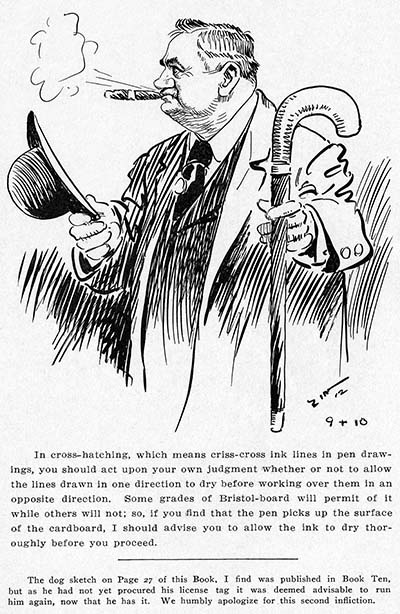

Zim’s Correspondence School of Cartooning, Comic Art & Caricature Volume 3: Books 11 to 15 (1914/1920)

Animation Resources is proud to present our third volume from the Zim course as a downloadable high resolution e-book. This PDF e-book is optimized for display on the iPad or printing two up with a cover on 8 1/2 by 11 inch paper.

REFPACK006: Zim Cartooning Course Vol. 3![]()

Adobe PDF File / 212 Pages

455 MB Download

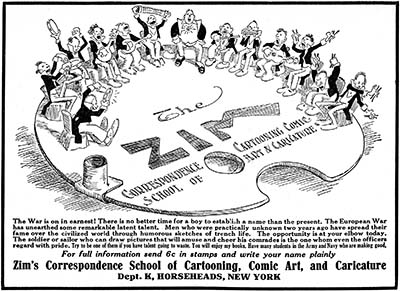

Advertisement for Zim’s Cartooning Course (ca. 1920)

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF EUGENE ZIMMERMAN

From Stephen Worth’s introduction to Zim’s Cartooning Course Vol. 3

When Eugene Zimmerman left the Alsatian region of France in 1869 at the age of seven to emigrate to America, he didn’t know exactly what the future might hold for him. Like many immigrants who made the voyage from the old world to the new, he left with little more than the clothes on his back.

Eugene’s mother died in childbirth when he was only two, and his father and older brother Adolph left France three years later to take a job in a bakery in Patterson, New Jersey. Eugene and his younger sister Amelie were left in the care of their aunt and uncle in the French town of Thann, near the Swiss border. But the Franco-Prussian war was looming on the horizon, and his guardians thought it best for little Eugene to join his father and brother in America. So he said goodbye to his younger sister, never to set eyes on her again, and booked passage in steerage on the Paraguay, an old fashioned steamer.

Twenty-one days later, he disembarked in New York City. Young Zimmerman crowded into the Battery in Castle Garden along with countless other immigrants. He was disinfected and his bedding from the voyage was cast into the sea. An aunt and uncle living in New York’s East side took him in for a while, but Eugene was eager to reunite with his father. He packed up and moved to New Jersey, where he was surprised to find that his father didn’t even know he had left France. Soon, Eugene was working alongside his father and brother in the bakery, greasing pans and delivering bread.

For a short time, his father sent him to a French tutor, but Eugene had little interest in the culture of his birthplace. Financial limitations finally forced him to attend public school, where his accent earned him the nickname, “Frenchy“. However, he didn’t identify himself as French. His overriding goal was to become an American through and through. He later wrote, “I soon learned to cuss and swear as perfectly as my American associates.“

Zimmerman took a number of odd jobs as a child to pay for his room and board- chore boy on a farm, fish peddler, assistant to a wine and beer merchant and newsboy. But his career really began in earnest when a traveling sign painter named William Brassington took him on as an apprentice. Brassington would take in orders from local businesses for advertising show cards and Eugene would letter and paint them. He learned to create huge display banners and flags, and letter in gold leaf in a variety of styles. Zimmerman decorated the interior of their sign shop with murals of landscapes, and Brassington started to offer Zimmerman’s illustrated advertisements as well as plain lettering to his clients.

Eugene’s work was noticed by a rival sign painter in the area, J.C. Pope, who hired him away from Brassington for $9 a week to head up the pictorial department in his workshop in Horseheads, New York. Zimmerman began to seriously study sketching, filling notebooks with doodles and cartoons copied from the pages of magazines like Harper’s Weekly and Puck.

Pope’s business eventually folded, and Eugene went to work for a large sign firm headed up by Joe Densmore in Elmira, New York. On a trip to New York City to visit his family, his uncle borrowed one of his sketchbooks and arranged for it to be delivered to the famous cartoonist, Joseph Keppler at Puck. The work was good enough to land Eugene an interview at the magazine; but unfortunately, Eugene had returned to Elmira by that time. Stranded without train fare, unable to take advantage of the opportunity of a lifetime, Zimmerman’s excitement dimmed. But Densmore took pity on the young artist’s situation, and lent him $10 for transportation to New York City to meet with Keppler.

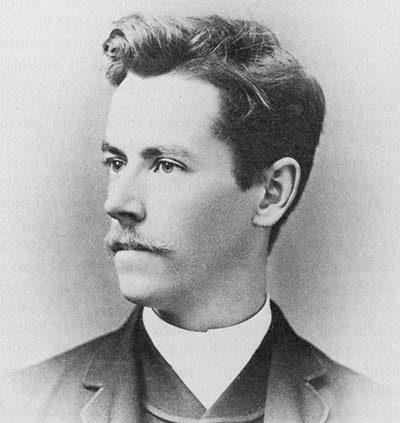

Eugene Zimmerman in 1896

In his autobiography (ZIM: The Autobiography of Eugene Zimmerman

Walter M. Brasch- Editor, Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press, 1988), Zimmerman described his arrival at the offices of Puck…

Outside the structure was gloomy and depressing; within, I found a cheerful bustle of clerks at desks. Somewhat relieved, I breathed my name and business into a receptive ear. The message wafted through a speaking tube to the great Keppler, three floors above, whereupon that high and mighty personage came down and met me.

Heaven’s gates opened up to me when I discovered that Mr. Keppler was merely a human being, albeit a bit pompous. He was a typical artist of the old school- a commanding figure with iron grey hair, mustache and a goatee of the Louis Napoleon type… After some discussion, a contract was drawn up in pen-and-ink and we all signed it. I was hired for a period of three years at five dollars a week the first year, ten dollars the second, and fifteen the third.

Before I was presented to Keppler, my imagination pictured his studio as a gorgeous showplace like an Arabian Nights dream. I expected to find the master cartoonist surrounded by medieval armor and tapestries, Chinese jade and incense burners. It never occurred to me that such a museum would be unsatisfactory as a workshop.

Keppler occupied a small clean enclosure in the Puck art department. A similar adjoining one was used by his lieutenant, Bernhard Gillam. The studios of those artists was about as imposing as the stalls of fine racehorses, yet in such unpretentious compartments were created the most wonderful cartoons that made political history during the big presidential campaigns of the 1870s and 1880s.

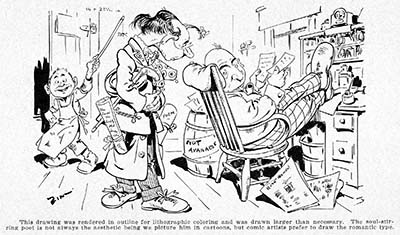

Puck was one of the first publications to take advantage of the development of four-color stone lithography and zinc plate printing. Prior to this, illustrations were laboriously engraved in blocks of wood. But at Puck, Keppler drew directly upon lithographic stones with grease pencil. When complete, the drawings were etched with acid to create the printing plates. Working as Keppler’s assistant, Zimmerman’s job was to help prepare the “tone stones“, the blocks of stone which created the subtle blends of color for which Puck was famous.

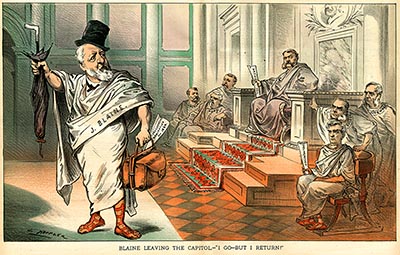

Center spread cartoon by Joseph Keppler from the December 21, 1881 issue of Puck

Keppler was a classically trained artist, and his cartoons exhibited the refined compositions and vivid colors of European oil paintings. He had gotten his start working for Frank Leslie’s Weekly. During an argument with the publisher over a $5 a week raise, he threatened to jump ship and launch a magazine of his own. Leslie assured him he would do everything in his power to drive him out of business if he tried it, but that didn’t deter Keppler. He hired the foreman of Leslie’s printing plant and began producing Puck as a German language publication loosely based on the British magazine Punch. It was so successful that in 1877, he launched an English edition.

Puck was not just a humor magazine- it was primarily concerned with political satire. Thomas Nast had established the precedent at Harper’s Weekly with his relentless attacks on Boss Tweed and the corruption rife within Tammany Hall. Tweed was eventually driven from power and fled to Spain under an assumed name. But anonymity eluded him- He was recognized on the basis of Nast’s published caricatures and the hounding continued. As Nast entered retirement, the popularity of Harper’s Weekly declined, and Puck rose to fame for its no-holds-barred attacks on corrupt American political figures, as well as its opinionated views of European politics. Puck also took aim at the Catholic and Jewish faiths, for which it generated considerable criticism. A Jewish organization threatened a boycott of Puck, but the publishers assured them that their purpose was not to offend but to entertain. Puck’s editor promised to be more careful in the future to avoid material that might be misinterpreted as anti-Semitic. The group was satisfied and called off the boycott, and as time went by, the objects of satire became more political in nature. The orientation was decidedly in favor of the Democrats, with Republicans the principle targets for mockery and derision.

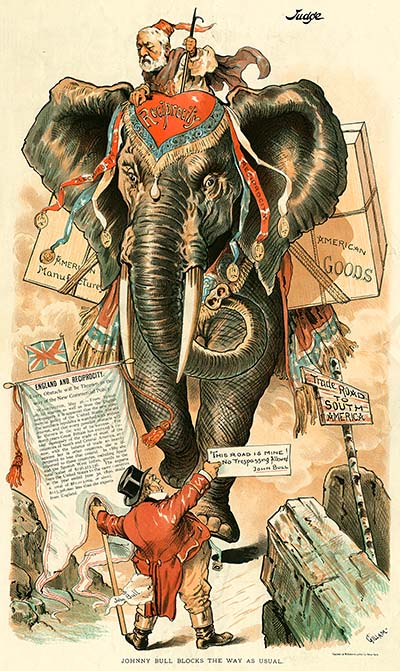

Competing head-to-head with Puck were Judge magazine, Police Gazette and Life. Judge stepped into the opposing political camp from Puck, favoring Republican candidates and skewering the Democrats. The Police Gazette’s stated mission was to provide information of interest to law enforcement officers, but it was just an excuse to print lurid stories of murder and outlaws from the Wild West, along with risque woodcuts of beautiful women. Life magazine took the high road, with “appropriate“ material appealing to the elite, in stark contrast to the rough-and-tumble content of its competitors. Zimmerman later reflected, “Puck had been vicious in its attacks on the Catholics and Jews. Life sidestepped religious prejudice, thus gaining the respect of all denominations…“

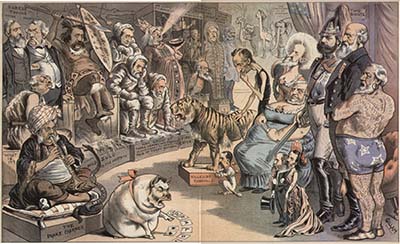

A center spread by Bernhard Gillam from the June 13, 1891 issue of Judge

Zimmerman was surrounded at Puck by some of the greatest names in cartooning- chief among whom was the English born Bernhard Gillam. A strong forceful line and meticulous and precise style was the hallmark of Gillam’s work. He was most famous for a cartoon he created during the presidential campaign of 1884. Gillam depicted the Republican candidate, James G. Blaine as a tattooed man in a freak show, his skin covered with slogans referring to the various scandals that peppered his career. The April 16, 1884 issue of Puck that featured the cartoon quickly sold out and additional printings were hastily arranged. Circulation doubled, and ultimately, over 300,000 copies of the issue were sold.

The Tattooed Man by Bernhard Gillam from the April 16, 1884 issue of Puck

The “tattooed man“ comic created a firestorm of controversy, throwing the spotlight on Puck. Gillam fed the flames with a series of variations on the same theme. Keppler and another Puck artist, Frederick Opper joined the fray to create a few “tattooed man“ gags of their own. The cartoons reached such a high level of public awareness that Pear’s Soap advertisements parodied them. (“Hurray! Soap to remove tattoos!“) The final election tallies between Blaine and his Democratic rival, Grover Cleveland were very close, and many attributed Blaine’s loss to Gillam’s cartoon. The irony of the situation was that Gillam himself was a Republican and voted for Blaine. Several years later, he was hired by the Republican magazine, Judge where Gillam attacked Cleveland with the same sort of enthusiasm that he had supported him during the “tattooed man“ days at Puck.

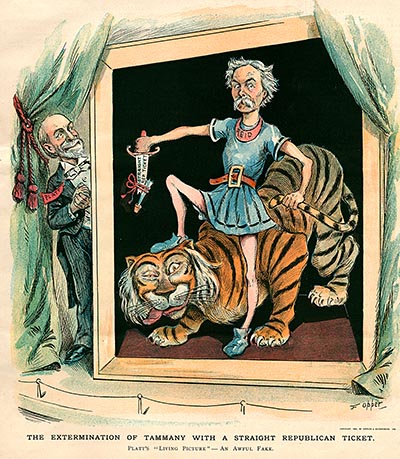

Another great cartoonist working for Puck during Zimmerman’s years there was Frederick Opper. Opper worked for Scribners on St. Nicholas Magazine before joining the staff of Frank Leslie’s Weekly. When Leslie died in 1880, Opper was engaged by Keppler on Puck, where he produced illustrations for the next 18 years. Opper later accepted an offer from William Randolph Hearst to create a comic strip for the New York Journal. Titled “Happy Hooligan“, the pioneering strip ran until failing eyesight forced Opper to retire in 1932.

Zimmerman doesn’t say much about Opper in his autobiography, but he describes him as “the recognized comic artist on Puck“ who generally had first pick of the material submitted for cartoon ideas by the editorial staff. Opper was very prolific, producing more art than any other artist on staff. Zimmerman wrote, “There were more Puck artists than there was white space to fill, so that often one man would have to give ‘way to make room for another’s work. This was a serious obstacle to my artistic advancement.“ It seemed clear that there wasn’t room at Puck for both Opper and Zimmerman.

Cover illustration by Frederick Opper from the June 27, 1894 issue of Puck

Around this time, Eugene Zimmerman made a change that would forever brand his art in the public’s mind…

Early in life, my long name became a burden, so I threw two-thirds of it overboard,

thus saving time space and India ink, and providing a merman for any sea nymph who

cared to salvage it. A friend, a very successful businessman noticed that my signature, “Zim“ had a downward slant. Said he, “Never sign your name downhill, always uphill. It looks more prosperous.“ From that moment, I have always signed my drawings uphill, for I believe there is truth in this assertation.

Fortune was soon to smile upon the newly named, “Zim“ with a change of scene, a change of lifestyle, and most of all, a change in employment.

Dissent was brewing on the Puck staff. Keppler and his partner Adolph Schwarzmann had made a deal with the editor, Henry Bunner that should Puck’s circulation increase significantly, Brunner would receive a $1,000 bonus. Word filtered back to Gillam that Bunner had collected on the deal. Since his “tattooed man“ cartoons were largely responsible for the jump in circulation, Gillam demanded a raise in salary from $100 to $125 a week. Keppler and Schwarzmann firmly refused, and Gillam began quietly investigating new avenues of employment.

Meanwhile, Judge magazine was experiencing hard times. Competition with Puck was fierce, and although Puck’s circulation had risen dramatically, Judge’s subscription base was hanging fire at a fraction of the size of its biggest competitor. Due to the combined efforts of Frank Beard and Grant Hamilton, Judge had begun to dig itself out of debt. But when a new buyer for the publication, entrepeneur William Arkell took over, Beard was out and Hamilton was put in charge. Investors who had a particular interest in backing a Republican rival for Puck flocked to the venture. Hamilton was given a fat bankroll earmarked for hiring the best talent available.

Bernhard Gillam was first on his list. Money wasn’t the only reason Gillam was interested in joining the staff of the newly reconstituted Judge- Gillam was a Republican himself, and his position creating editorial cartoons at Puck was in essence a job as a “hired gun“. Gillam confided about the opportunity at Judge with the only other Republican on the Puck staff- Zim. At Puck, Zim was just another artist competing for space

with older, more established artists. Hamilton promised him that Zim could submit as many cartoons as he wanted to Judge with complete freedom in regards to theme. Gillam and Zimmerman resolved to resign Puck together, and join Arkell and Hamilton at Judge.

The parting with Puck was not friendly. Gillam and Zimmerman’s output was important enough to Puck to force Keppler and Schwarzmann to hire five artists to replace the two departing ones. The men in charge of Puck were certain that Judge would fold and Gillam and Zim would return in defeat. But it wasn’t Judge that would suffer a decline. With the departure of Gillam and Zimmerman, Puck began a long slide in quality and circulation from which it would never recover. At Judge, Gillam and Hamilton went to work revitalizing the publication’s antiquated editorial policy, inadequate printing facilities and second-rate staff. The first issue of the new Judge hit the stands at the beginning of 1886. It was a resounding success.

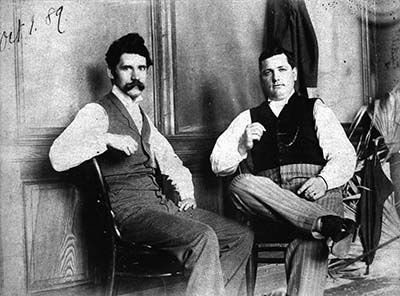

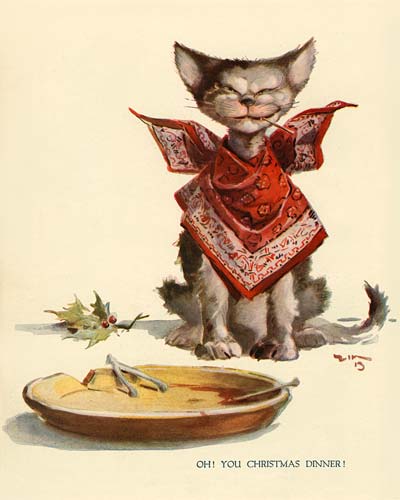

Bernhard Gillam and Grant Hamilton in 1889

Freed from the restraints placed upon him at Puck, Zim set to work at a white heat. He began exploring the possibilities of humorous situations arising from the lives of people like himself- the immigrant classes. While cartoonists at other magazines depicted distinguished aristocrats and political celebrities in fancy sitting rooms, Zim favored subjects from the streets, reveling in ethnic humor. He made fun of all groups equally- ignorant farmers, tradesmen, Blacks, Irish, Italians, Jews, Germans, cowboys, Indians, cops, crooks, street urchins, mangy cats and old hound dogs- Zim took inspiration in the diversity of unique personalities that made up the melting pot of America.

Privately, Gillam was not happy with Zim’s choice of subjects. He felt that Zim’s caricatures were grotesque and coarse and would have preferred to pattern Judge on Puck at the peak of its success. But Hamilton and Arkell believed that Judge would never succeed solely as a vehicle for political cartoons. Their vision for the magazine was to feature more humor and less politics. Zim’s cartoons poking fun at both rural and urban life fit perfectly within the scope of their plans.

Zim made many changes in his life all at the same time. In addition to joining the staff of Judge in 1886, he married Mabel Alice Beard and set up housekeeping in Brooklyn. To add to the upheaval, a short time later his father became ill and passed away. Zim worked very hard, both on his duties for Judge and freelance projects, burning the candle at both ends. Eventually, the stress drove him to nervous collapse. He sold his stock in Judge and took five months off, recuperating in Florida. When he returned, he set up residence in Horseheads, New York, commuting to the city to work for two weeks of every month. Zim and his father-in-law began work on building a home for the family, which by this time included a daughter, Laura, and an adopted son, Adolph.

For Judge, Zim generated a flurry of brilliant political cartoons, as well as caricatures based on his experiences vacationing in the deep South, life among the poorer classes of New York and the rural characters that populated his new home of Horseheads. Along with Bernhard Gillam, his brother Frank Victor Gillam and Grant Hamilton, Zim helped to build Judge up into a publishing empire.

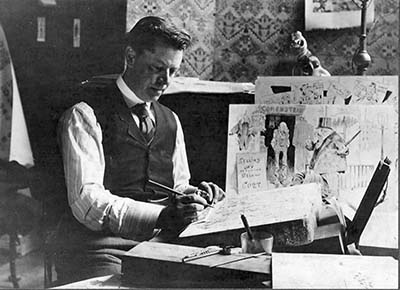

Zim at his drawing board in his home in Horseheads, (mid 1890s)

In 1896, Zim’s friend and associate, Bernhard Gillam died of typhoid fever. By this point, the artists of Judge had scattered themselves across the country, sending in their artwork by post. Arkell called the remaining art staff back to New York and divided Gillam’s salary and percentage of sales equally among them. The art department pulled together as a team, spending more time at the Judge offices in the city. Hamilton was appointed Art Director, and with Gillam gone, the magazine veered even further away from current events to more humorous subjects. During this time, Zim forged a close friendship with Grant Hamilton, spending countless hours with him roaming the streets and slums of New York in search of interesting character studies. As time passed, Hamilton’s artwork loosened up and acquired more specific aspects of caricature. It was clear that as an artist, he benefited from his close friendship with Zim.

The mid-1890s was the time when Zim’s artistry was at its very peak, and he wasn’t alone. The art staff of Judge consisted of a virtual “who’s who“ of cartooning. In addition to Hamilton and Zim, the roster of cartoonists included Hy Mayor, Richard Outcault, A. S. Daggy, Emil Flohri, Frank Livingston Fithian, George R. Brill, C. T. Anderson, Peter Newell, J. H. Smith, Sydney B. Griffin, F. Victor Gillam, T. S. Sullivant, Michael Angelo Woolf, Gus Dirks, and an up-and-coming youngster named James Montgomery Flagg.

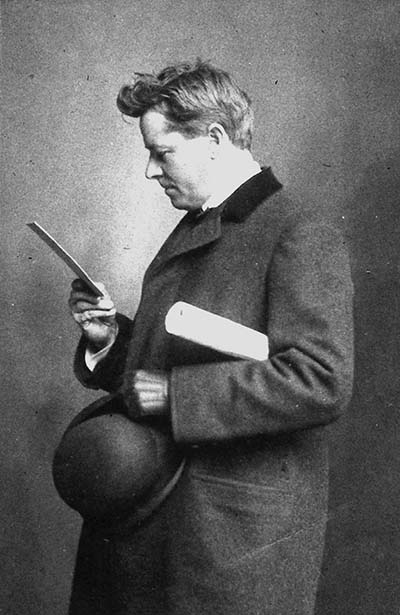

Zim dressed for a trip to the city in 1886

In 1901, William J. Arkell resigned (or was forced out of) the management of Judge. He was replaced by an attorney named Austin Fletcher. Fletcher was disliked by just about the entire artistic staff of the magazine. Hamilton resigned to form a new publication, Just Fun, which only survived a few issues. Zim distanced himself more and more from the management at Judge. Eventually Fletcher was forced out by John A. Sleicher, the former editor of Leslie’s Weekly. Hamilton returned to his post as Art Director and things went back to the way they had been for a time. But Sleicher was unsure about which direction the magazine should take. He waffled back and forth, giving contradictory instructions to the staff. The publication drifted and gradually lost its edge. Too much work, combined with the recent loss of his beloved adopted son Adolph to tuberculosis, and his disenchantment with Sleicher’s mismanagement threw Zim into a period of depression. He eventually quit full time employment with Judge in 1912 to work freelance from his home in Horseheads.

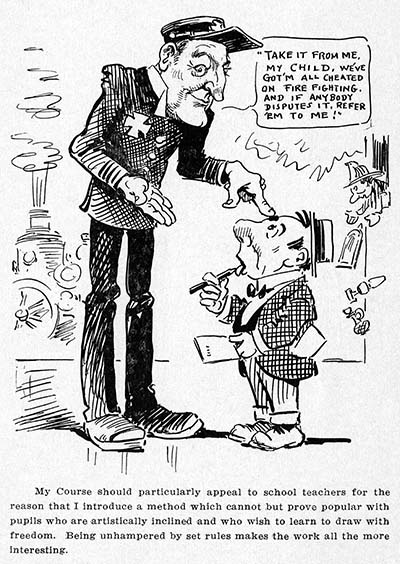

In 1905, in response to requests from his readers, Zim authored a small “how to“ book titled This And That About Caricature. Written in an anecdotal, chatty style, the book didn’t attempt to be an art instructional text as much as a statement of the philosophy of a cartoonist. It sold well enough to attract the attention of a mail order school, The Correspondence Institute of America. Zim revised the book and licensed it to the company for use in their course, but soon discovered that the organization was a fly-by-night fraud, bilking thousands of students. Even so, the company raked in a considerable amount of money on the basis of Zim’s name. So Zim resolved himself to create a real course to do what the C. I. of A.’s course had done dishonestly.

Zim at work in the offices of Judge around 1905

Zim’s Correspondence School of Cartooning, Comic Art and Caricature consisted of twenty 32-page books packed with artwork, practical advice, homespun philosophy and plain old horse sense. Every month a new book would arrive in the mail, and the student would be responsible for arranging to ship their completed assignments to Horseheads where Zim would review and critique them for a small fee. Along with the income he generated doing freelance illustration work from home, Zim was able to bring in a steady income from the course without having to commute to New York City.

During this time, Zim undertook to publish several small books marketed directly to the communities of Horseheads and Elmira, New York. Zim’s Foolish History of Elmira (1912) contained amusing drawings and stories regarding the town’s past, caricatures of prominent citizens, and a few pages of advertisements for local merchants. It sold for a nominal fee on the countertops of shops and newsstands in the area, and led to three separate editions of Zim’s Foolish History of Horseheads in 1914, 1927 and 1929.

Paul T. Gilbert, the editor of Cartoons Magazine, an anthology of political and humor cartoons from around the world, came across one of Zim’s “foolish histories“ and hired him to write a column for the magazine titled, “Homespun Phoolosophy by Zim“. In 1926, Gilbert established the first trade organization for cartoonists, The American Association of Cartoonists and Caricaturists. Zim was elected president, and the other officers included Rube Goldberg and Bud Fisher. But Cartoons Magazine folded in 1927 and the AACC dispersed soon afterwards.

Watercolor sketch by Zim for Judge (1913)

Zim dabbled in sequential comic strips, but his metier was magazine cartoons, not newspaper comics. In his later years, he freelanced with several magazines and wrote a daily newspaper column. But most of all, he wrapped himself in the comfortable surroundings of Horseheads, serving with the volunteer fire department, sponsoring a local brass band and participating in local politics. The citizens of Horseheads were largely unaware of how famous their resident cartoonist had been in his day. His work at Puck and Judge faded into the past, partly due to the passage of time, but also because Zim’s brand of ethnic humor had gone out of style. By the time he died of a heart attack at age seventy-three in 1935, he had largely faded from public memory. The community of Horseheads mourned his loss most of all.

As the decades have rolled on since Zim’s passing, he has come to be routinely omitted from accounts of the history of cartooning. Although Thomas Nast, T. S. Sullivant, Frederick Burr Opper, Richard Outcault and James Montgomery Flagg are frequently mentioned in histories of cartooning and illustration, Zim’s name is conspicuous by its absence. When he is mentioned at all by historians, it is in reference to the “political incorrectness“ of his humor. But Zim’s legacy is more important than history gives him credit for. His contribution to American culture is both historical and artistic.

During the last decades of the 19th century, America was a land being built by poor, hard-working immigrants. Zim was one of them. He took caricature out of the drawing room and into the streets. When Zim entered the business, cartooning existed to glorify (or more often, defame) famous American political leaders. Zim took caricature further, poking fun at the real Americans of the day- the people he saw in the streets of the Italian, Jewish, Black and Irish districts of New York City.

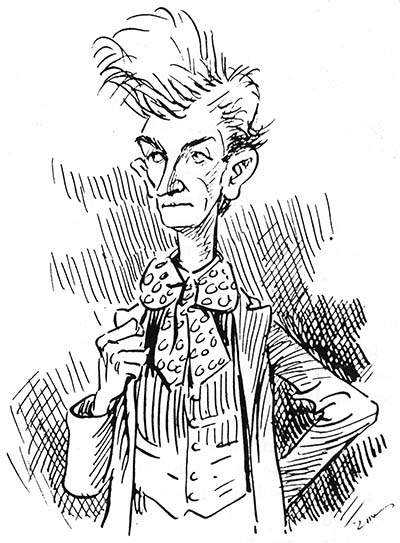

Self Caricature of Zim

When they mention his work at all, historians frequently describe Zim cartoons as typical examples of “ugly racial stereotyping“, but nothing could be further from the truth. Zim didn’t deal in stereotypes. His comedic sensibilities may have mirrored the ethnic humor of the day- the same sorts of gags found in knockabout comedy routines in Vaudeville shows, humorous dialect monologues on phonograph records, or even in the jokes and stories told by the common people he was depicting. But Zim’s true genius isn’t contained in the gags themselves. The value of Zim as an artist lies in the way he presented the characters and situations.

Eugene Zimmerman didn’t invent his racial imagery from whole cloth, and he wasn’t just repeating a formulaic stereotype. Zim reflected his world through the art of caricature. Every element of a scene was carefully observed and artfully exaggerated to create an image that was beyond real- a distillation of the larger reality. In his cartooning course, Zim charts the progress of a man’s boot, from new and shiny to beaten down and decrepit. He analyzes what sort of shoes might be worn by a particular type of man- be he hobo or aristocrat. This level of observational detail extended to all aspects of his sketches, from the likeness of the facial features to the character’s clothing, to the furniture and room that surrounds him.

These precious drawings are a priceless window into the past. More than a hundred years later, we are fortunate to be able to see the world of the 1890s through Zim’s observant eyes. Zim’s fondness for the common man is apparent in every line that flowed from his pen. He didn’t just achieve his boyhood goal of becoming American through and through; utilizing the art of caricature, he vividly documented the day-to-day reality of millions of others Americans just like him.

Not A Member Yet? Want A Free Sample?

Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month!

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content