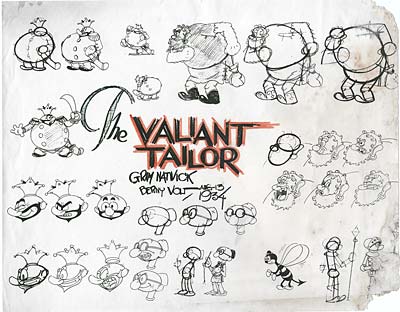

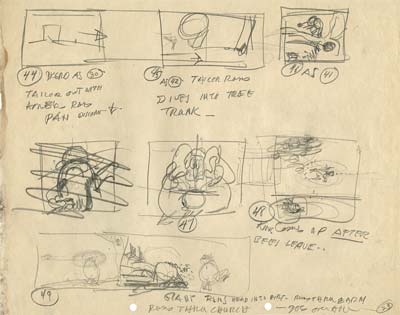

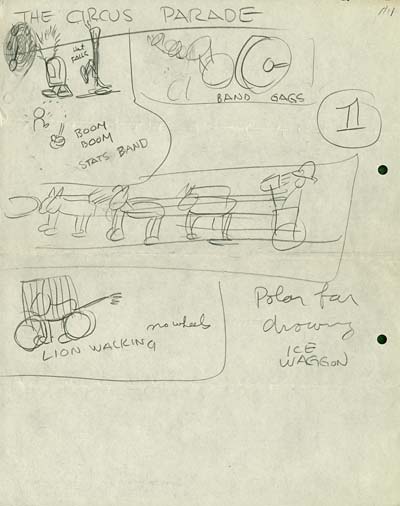

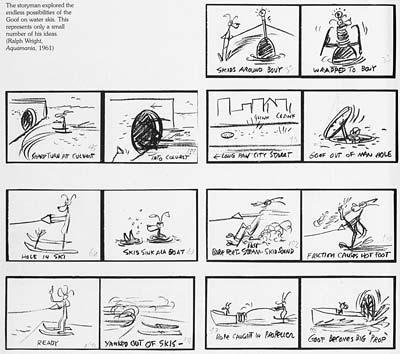

Individual gags, created at the initial story meeting

are gathered together. The story man creates an outline

to begin to work these unrelated gags into a continuity.

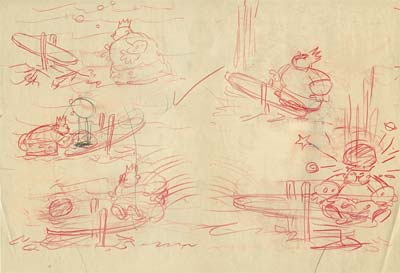

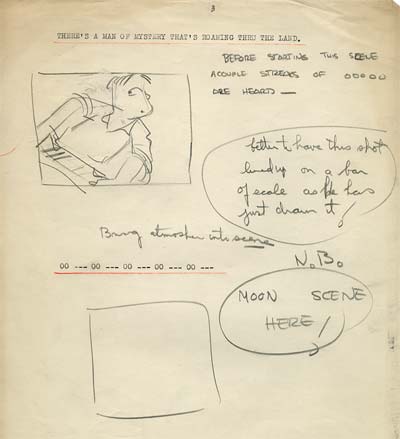

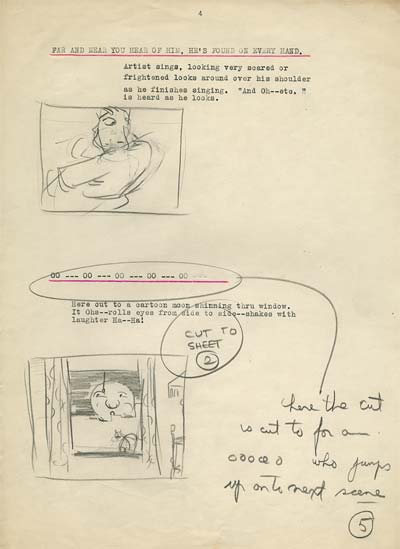

When we left off in our series of posts on cartoon writing last time, the initial "No No Session" had generated a pile of unrelated thumbnail gags on a basic premise which were starting to lead to the beginnings of a rudimentary plotline. Today, we’ll explore how the cartoon writers brought structure to the story and began to flesh out the continuity in preparation for the storyboard artist to begin work.

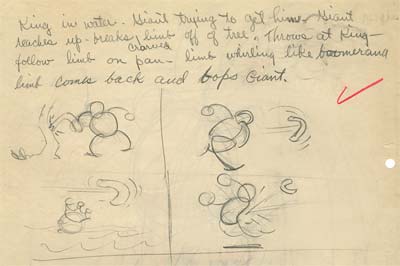

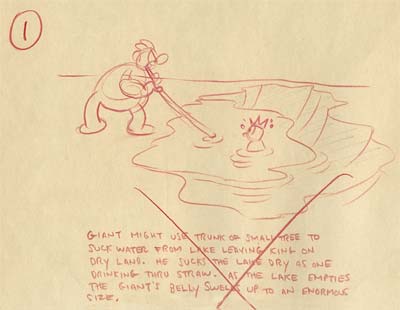

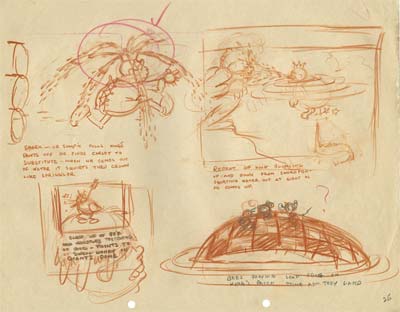

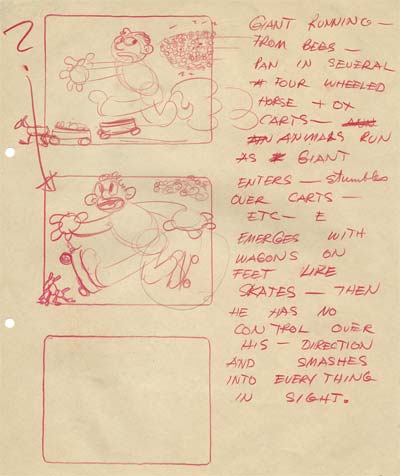

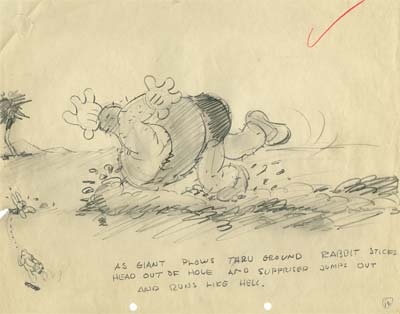

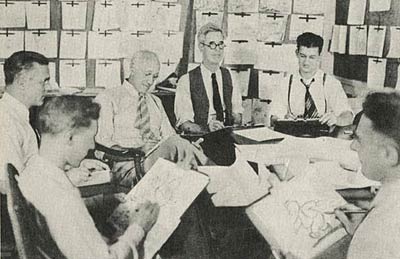

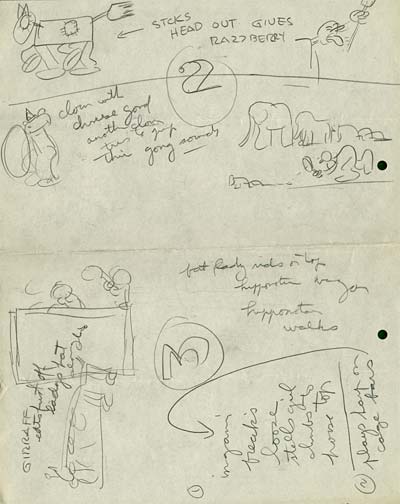

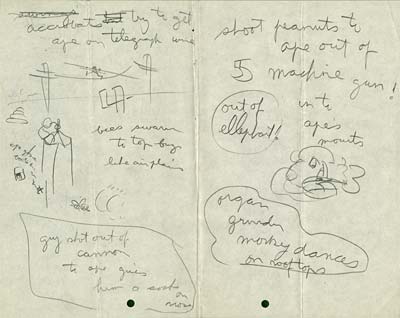

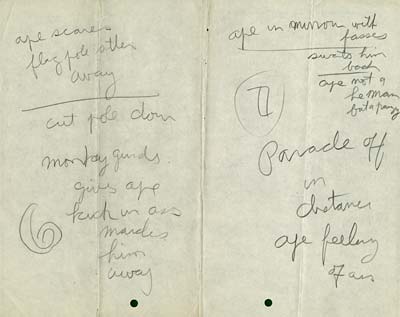

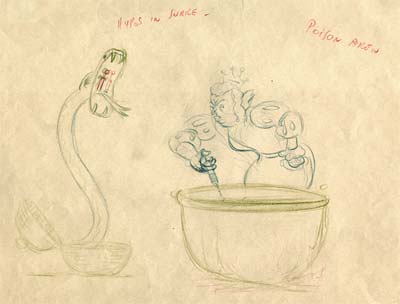

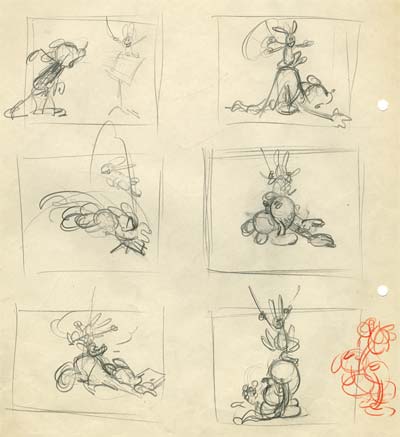

In the mid-1930s, Disney story sessions were transcribed by secretaries and widely distributed among the staff. All of the employees, from the directors all the way down to the janitors, were invited to submit gags to the cartoon being developed. The only stipulation was that the gags had to be drawn- not written down. Walt and the story men sifted through the doodles and stick figure drawings to find inspiration for little bits of business that they might not have thought of themselves. If the gag was usable, the employee was given a dollar bonus. If the gag led to a sequence of gags, they were paid five dollars. Here’s a typical "dollar gag" from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs…

In an interview many years later, Ward Kimball recalled that he would supplement his income by generating "dollar gags" in his spare time… His ideas were almost always used, but he soon discovered that he could get five times as much by simply attaching a "butt joke" to the end as a payoff. Inevitably, the "fanny gag" would appeal to Walt’s unique sense of humor, and he would choose Kimball’s gag as one that might lead to a sequence of gags- Bam! Five bucks!

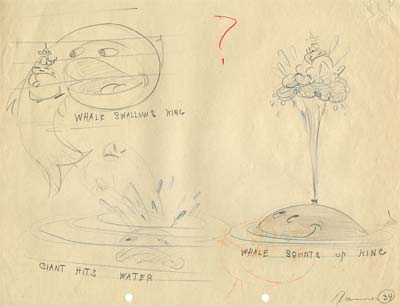

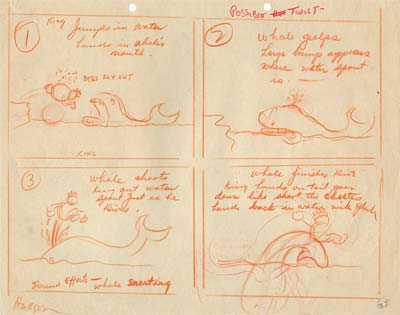

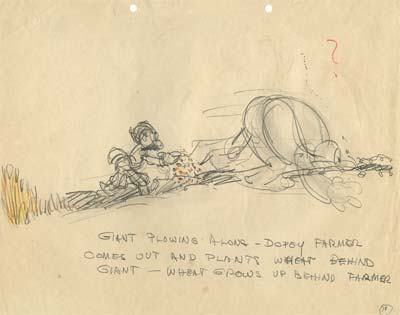

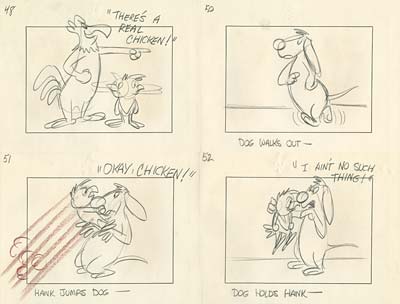

Kimball wasn’t the only artist who knew Walt’s preferences when it came to gag ideas… Here is a short sequence of story doodles by Les Clark. This "butt joke" was created for a sequence that was eventually cut from Mickey’s Grand Opera (1936)…

Clark is beginning to see an individual gag as a series of actions that relate to each other. His thumbnail sketches suggest enough for a storyboard artist to begin to tighten up his poses, focus the action and define the staging.

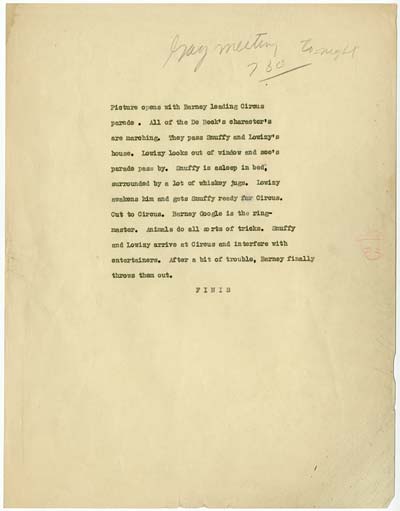

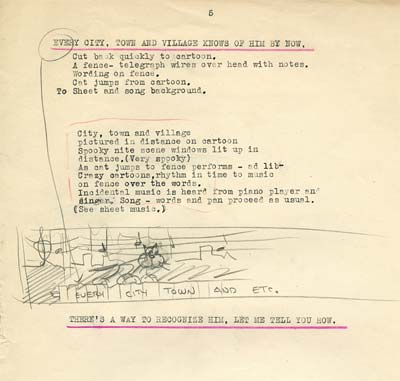

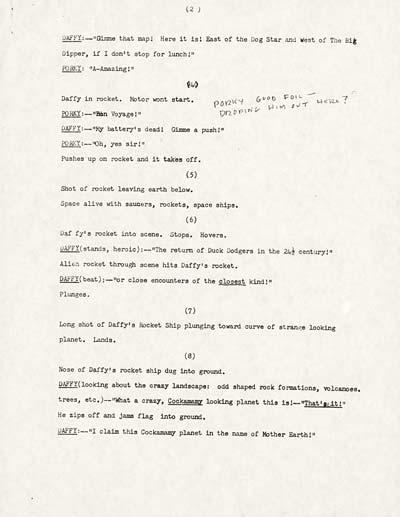

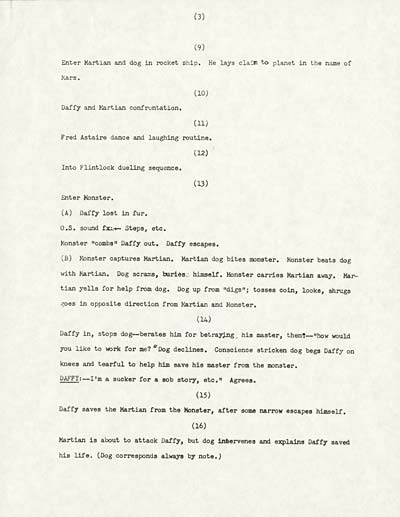

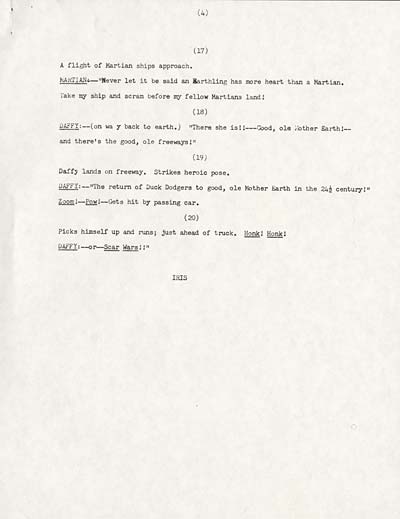

As soon as the gags started to come into focus as a basic plotline, the story supervisor would begin arranging them into a logical progression, formatting the embryonic scenario as a written document in outline form. The outline was the equivalent of the "first draft script" for an animated film. But it didn’t include dialogue and descriptions of actions the way live action scripts do. Instead, it defined the structure, continuity and intent of the action.

STRUCTURE

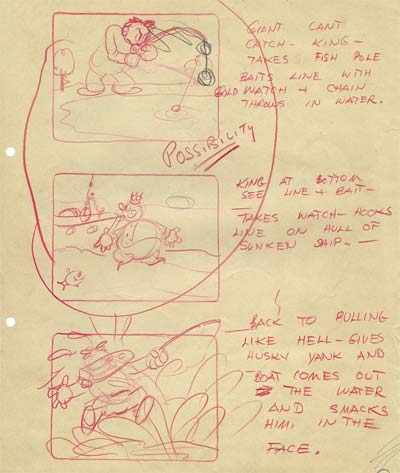

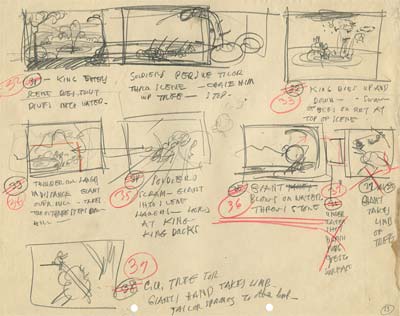

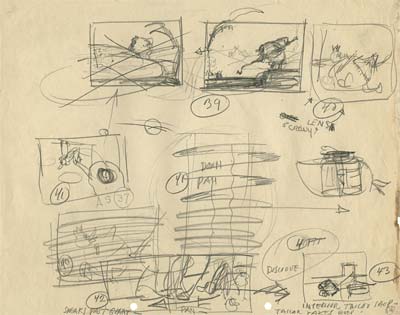

In preparing the notes for the storyboard artist to work from, the story supervisor began by establishing a structure to the gags. It was important to clearly define how the story broke down into sequences and how each sequence broke down into individual gags, because the storyboard artist most likely would not be boarding it in chronological order. The artist often drew up the payoffs to the storyline first- it was easier to create a strong setup when he knew where he was going to end up. The outline helped determine the breaks in the story, so the artist could work in an order that made sense for him.

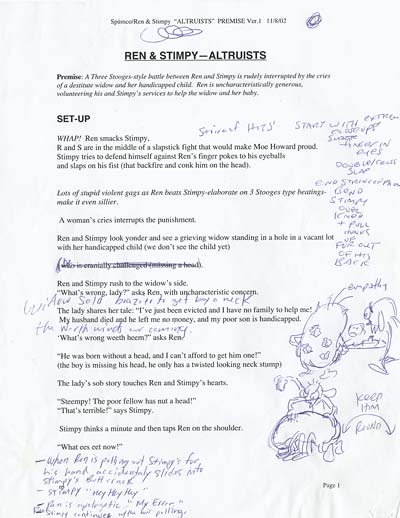

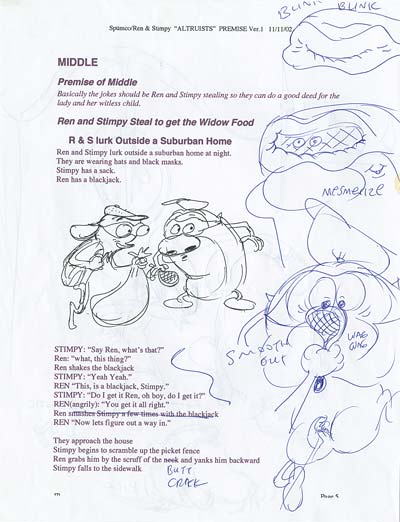

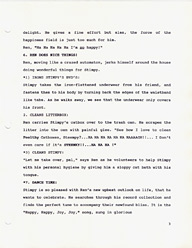

Here we have an outline from the Ren & Stimpy Adult Party cartoon Altruists prepared by Ren & Stimpy story man, Richard Pursel. John Kricfalusi’s director’s notes and doodles for the main setups appear in the margins…

Notice that the document begins with the statement of the premise, and is broken into sections defining the beginning, middle and end, as well as the sequences which fall within those sections. The structural detail goes all the way down to individual gags.

The line breaks make it easy for the storyboard artist to cut up the outline with scissors and pin the individual story beats up on his cork board as a placeholder for action he hadn’t boarded yet.

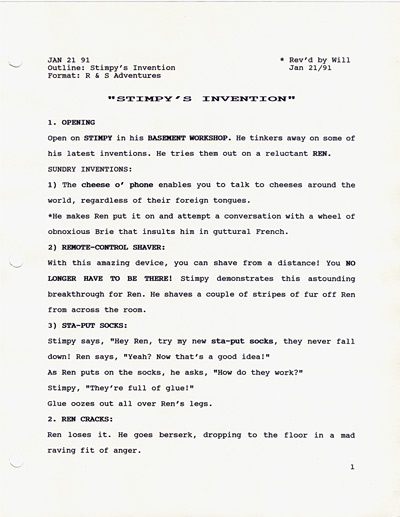

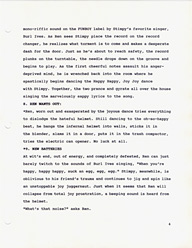

Here is a very detailed outline for Stimpy’s Invention…

CONTINUITY

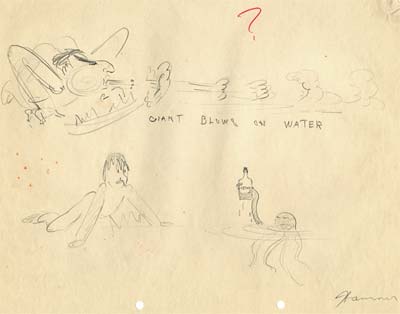

The second element that the outline defined was the continuity- the basic flow and logical order of the action. The storyboard artist would receive the doodles from the "No No Session" to work from, so there was no need for detailed descriptions of action. As the old saying goes… "A picture is worth a thousand words" and nowhere was that adage any truer than in cartoon writing. Story artists were accustomed to working from thumbnail sketches, and they could extrapolate the essense of a gag better from a quick sketch than a whole script full of fancy prose.

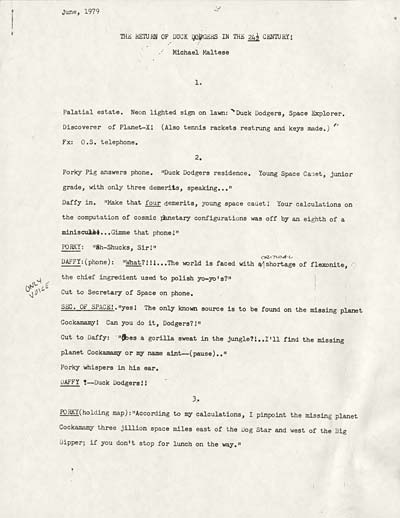

Here we have an outline for The Return Of Duck Dodgers In The 24 1/2 Century by Mike Maltese, one of the greatest cartoon writers who ever lived. Although this document is from very late in Maltese’s career, it clearly shows his creative process. This particular draft is a transitional document. Maltese had already begun boarding when this document was drafted. The first eight sequences and sequences 18, 19 and 20 appear to include dialogue transcribed from the finished storyboard. The middle section, however is in raw outline form, with very basic descriptions only intended to remind him of which thumbnail gag drawing went where in the continuity. As the storyboard developed, these notes would be updated with dialogue, transforming the outline from being a structural document to being a dialogue script, ready for the voice actors to perform.

If one looked at notes like these out of context, without the knowledge of the visual devolopment that preceded it and the purpose this document serves to the steps that follow, one might mistakenly assume that the story is being written in words. But nothing could be further from the truth. The words merely serve to organize the drawings. The storytelling is all being devised visually.

INTENT

The third, and perhaps most important thing that a storyboard artist required from the notes prepared by the story supervisor was the intent of the action. The cartoon had a purpose, which was stated in the premise. The beginning, middle and end of the story all had purposes as well. If an event in the beginning set up a payoff later in the story, the storyboard artist would need to be made aware of that.

The stories for cartoon short subjects generally broke down into a beginning, (which first established the characters and then the situation they found themselves in) variations on the theme of the premise in the middle of the cartoon, (referred to at Warner Bros as "blackouts") and the "topper gag" and resolution to the situation which formed the end. Every individual gag had to serve the purposes of the sequence it was a part of- all of the parts worked together to tell the story.

In our next installment on cartoon writing, the stage has been set for the storyboard artist to begin blocking out the action and establishing the cinematics…

You won’t want to miss the amazing examples of thumbnail boards that I’ve unearthed!

A SIDE NOTE: I’ve recommended it before, but if you haven’t seen the DVD of The Unknown Chaplin, you owe it to yourself to pick up a copy. The process of writing for animated cartoons grew out of the way slapstick comedy shorts were written. In fact, several animators and cartoonists served as gag writers for famous comedians in their younger days. This DVD breaks down Chaplin’s creative process and shows you exactly how his films were written. The program that deals with Chaplin’s masterpiece, City Lights should be required viewing for storyboard students at every animation school.

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of an online series of articles dealing with Instruction.