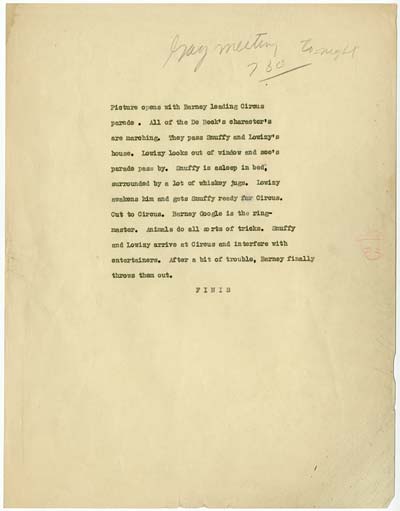

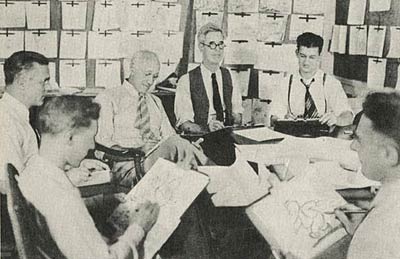

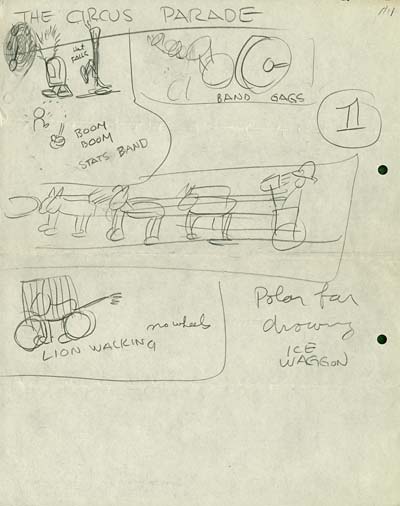

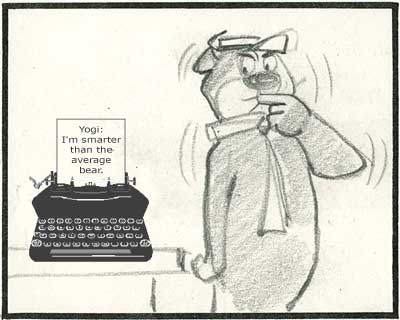

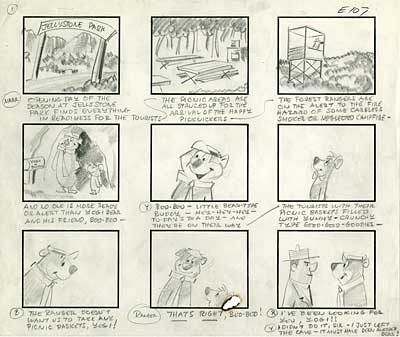

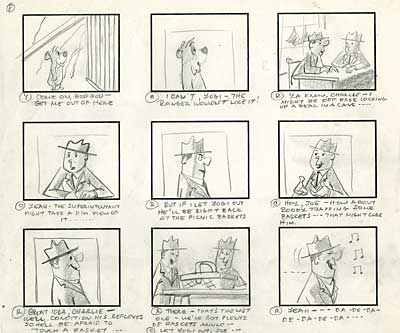

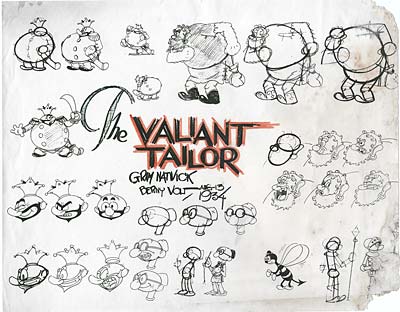

When I was beginning to draft this series of articles, I remembered a folder of thumbnails that Grim Natwick’s family gave me. The folder was labelled "Valiant Tailor Gags". I thumbed through the drawings several times over the years, but I only looked at the drawings individually- I didn’t look at them as a group. I pulled the folder out this week and upon closer examination, I discovered that the drawings formed a clear record of a gag session from 1934. This set of sketches is particularly important because it shows how the gags were created, how they evolved and grew as the artists discussed them at the story meeting, and how they found their way into the continuity of a finished cartoon.

The basic premise of this sequence is… The King is being chased by bees. He dives into a lake to escape them. The Giant arrives and harasses the King. The Tailor defeats the Giant and saves the King. Grim Natwick directed this cartoon, and his notes appear on the drawings in red. A check mark indicates that the gag is approved for the film. A question mark indicates that he isn’t sure where to use it yet.

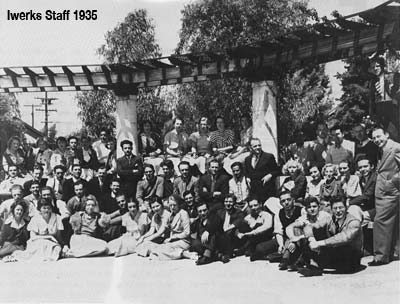

Here are some of the gags that the staff of the Iwerks Studio came up with for this premise. At the end is a Quicktime movie of the complete cartoon, so you can see how these plans were realized in the finished film.

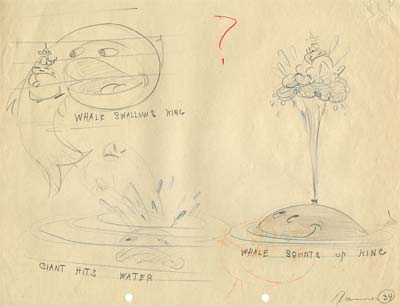

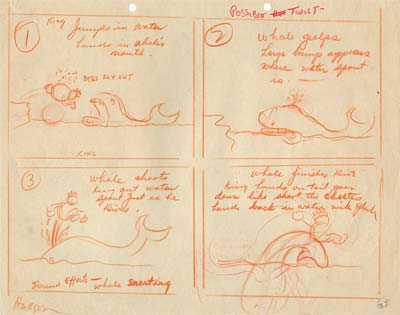

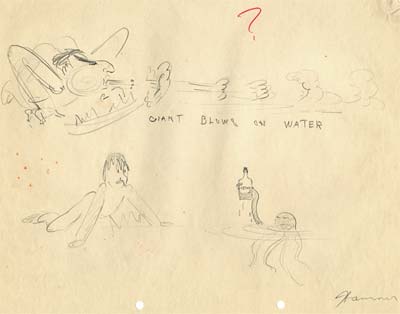

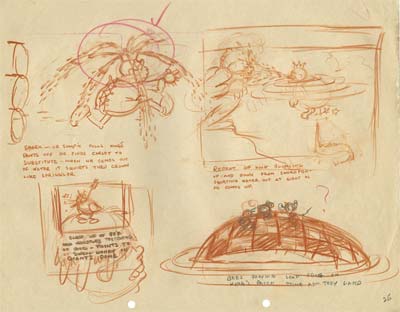

William Hamner suggests a gag where the King is swallowed by a whale and is shot out his blow hole. (Since the character design hadn’t been established yet, Hamner draws the character as Otto Soglow’s Little King!)

An artist named Hudson elaborates on Hamner’s basic idea, adding a tail flip to the end.

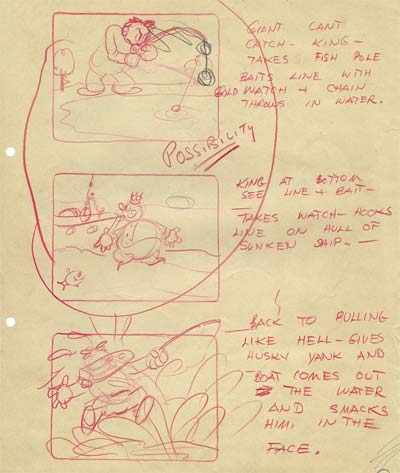

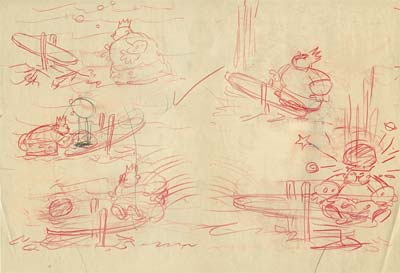

This gag suggests that the King be underwater, hiding from the Giant. The Giant tries to catch him like a fish with a gold watch as bait.

Underwater, the King uses a looking glass as a teeter totter.

The Giant blows on the water and a passing octopus offers him Listerine.

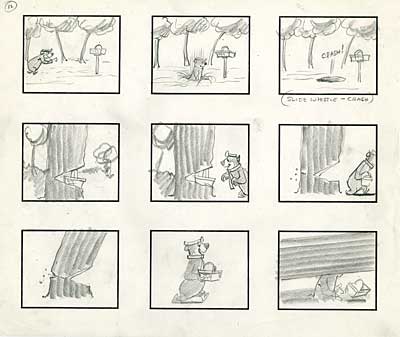

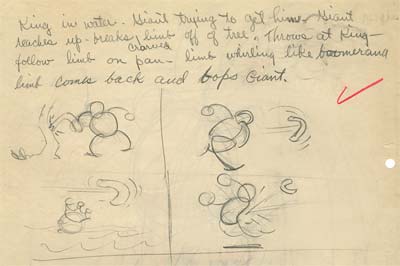

Ed Friedman suggests a gag where the Giant breaks a limb off a tree and uses it as a boomerang.

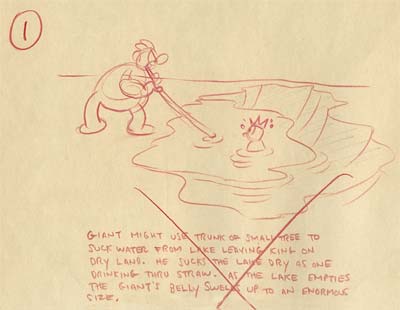

Another variant on the broken tree branch- The Giant uses it as a straw to drink the lake dry.

Several unrelated gags: The King runs out of the lake with streams of water from his crown. / The King is poked in the butt by a sword fish. / The Giant gets honey poured on his head. / The King is stung by bees on the patch on his butt.

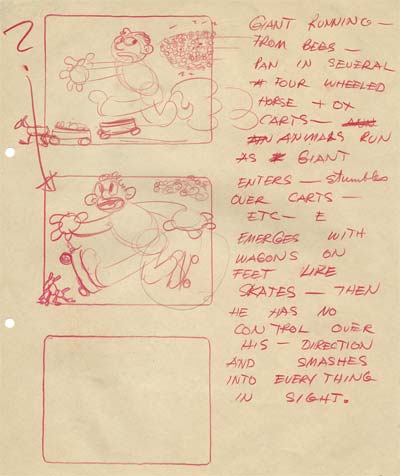

The Giant runs from a swarm of bees and stumbles over some wagons.

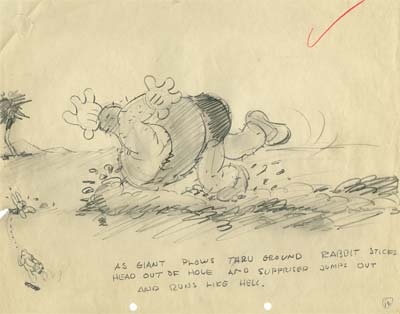

Grim suggests a gag where the Giant takes a header into the dirt, plowing the ground in a furrow.

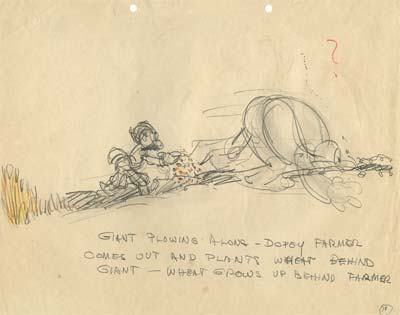

He attempts a topper gag with a farmer using the Giant to plow his field.

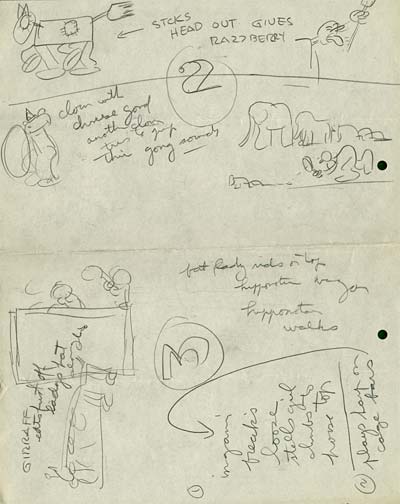

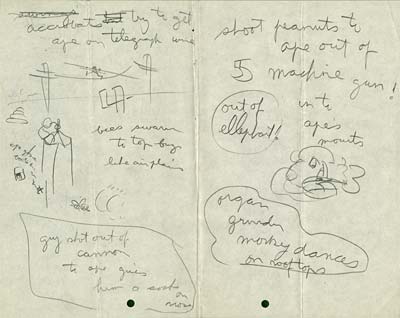

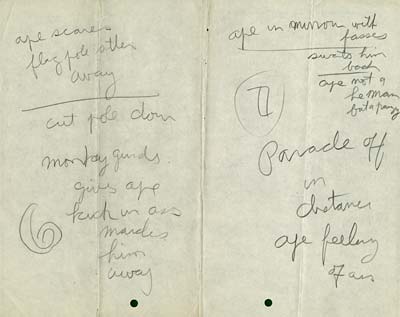

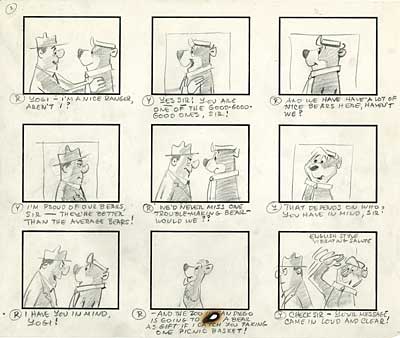

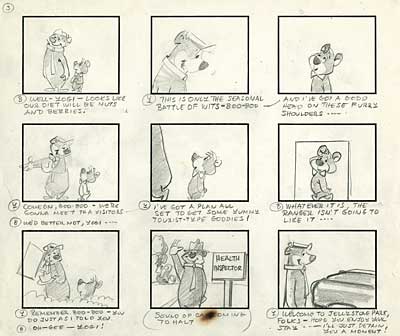

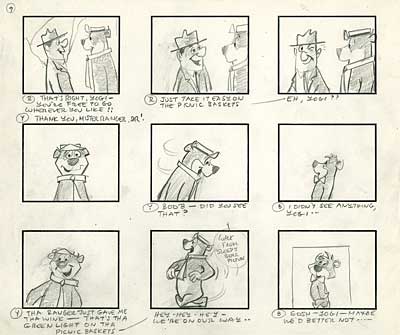

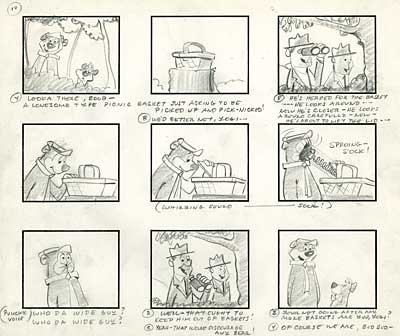

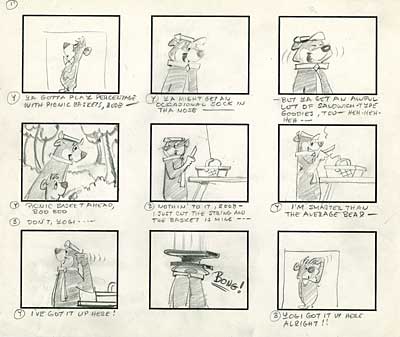

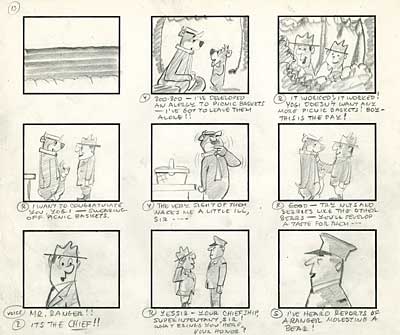

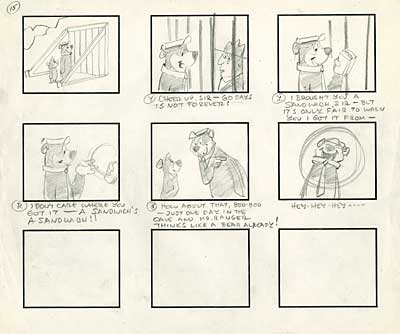

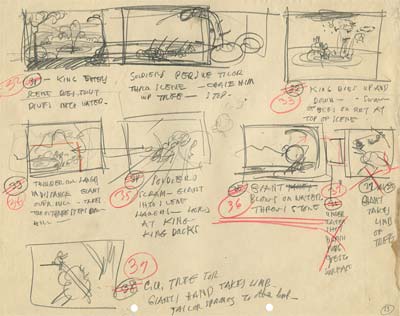

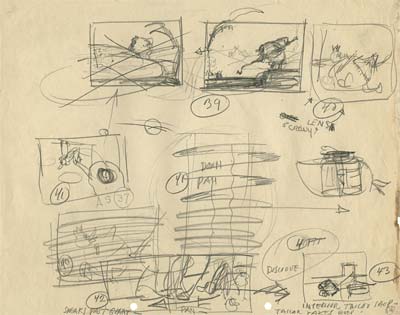

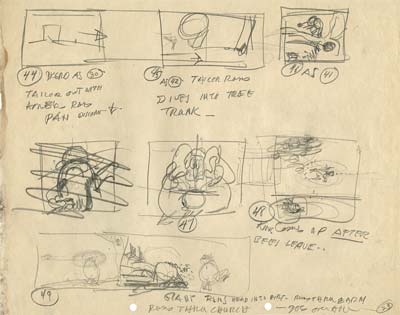

Now comes the really interesting part! Here are Grim Natwick’s thumbnails showing how he takes the random gags and works them into a rough continuity. The drawings are very rough. You might want to print them out so you can compare them to the finished film.

- (32) The King enters scene and does a trout dive into the lake to escape the bees. We pan with the soldiers as the pursue the Tailor and chase him up a tree.

- (33) The King bobs up and down in the water as the bees circle in a repeating cycle above him.

- (34) A thunderous laugh is heard in the distance. The Giant steps over the crest of the hill and takes a few steps over them.

- (35) The Giant scares the soldiers away. He looks at the King and laughs. The King ducks.

- (36) The Giant blows on the water and throws a stone at the King.

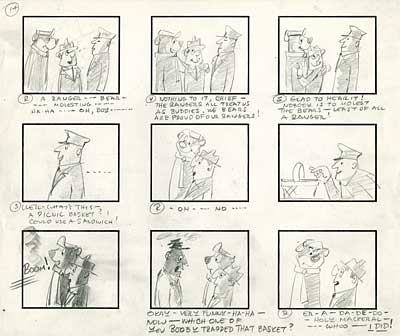

- (37) The King reaches up into the tree and grabs a branch. The Tailor jumps to another branch.

- (39) The Giant uses the branch like a gaffing hook, reaching to catch the King with it.

- (40) The hook at the end of the branch catches in the patch on the King’s butt.

- (41) The Tailor sees what is happening and ducks into a hole in the tree. The camera pans down the outside of the tree to its base, where the Tailor crawls out of another hole.

- (42) The Tailor sneaks past the Giant and runs off screen

- (43) Dissolve to: Interior tailor shop. The Tailor grabs a jar of honey.

The sequence went from here to the storyboard stage, where the action was defined better and the gags were plussed. Watch the film and see how it came out…

The Valiant Tailor (Iwerks/1934)< (Quicktime 7 / 7 minutes / 18.5 megs)

The next article in this series will show how the structure of cartoons became more sophisticated in the mid-1930s, and the development of organizational tools that made that possible.

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of an online series of articles dealing with Instruction.