"I think [Al Capp] had a lot of talent, no question. He was a good artist. He could capture the peak expression- what made something ultra-funny or ultra-nasty or ultra-cute. He was a very brilliant guy, although a little screwed up. But he was talented, no question. I think he was quite the artist." –Frank Frazetta, Comics Journal Feb. 1995

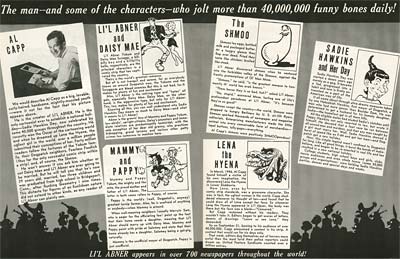

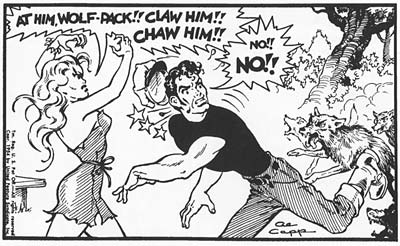

![]() Al Capp had been the uncredited and underpaid ghost for Ham Fisher on Joe Palooka, an experience so unpleasant that he made it a point to value his own assistants. Some of them, like Andy Amato and Harvey Curtis, made whole careers with him. Capp’s key assistant staff received a generous incentive- ten percent of the profits the strip generated, on top of their regular salaries.

Al Capp had been the uncredited and underpaid ghost for Ham Fisher on Joe Palooka, an experience so unpleasant that he made it a point to value his own assistants. Some of them, like Andy Amato and Harvey Curtis, made whole careers with him. Capp’s key assistant staff received a generous incentive- ten percent of the profits the strip generated, on top of their regular salaries.

Beginning in 1954, a young Frank Frazetta was paid the then princely salary of $500 a week- primarily to pencil the Sunday sequences from Capp’s roughs. By his own account, Frazetta enjoyed a one-day work week for years, allowing him to play baseball the other four days! Capp eventually put a stop to Frazetta’s 8-hour work week by halving his salary. But Frazetta quit instead, in January of 1962.

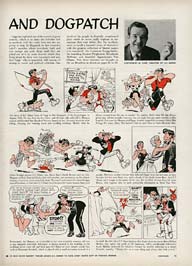

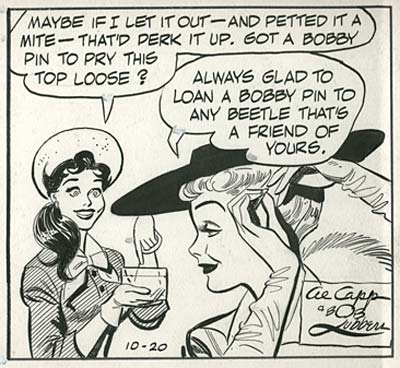

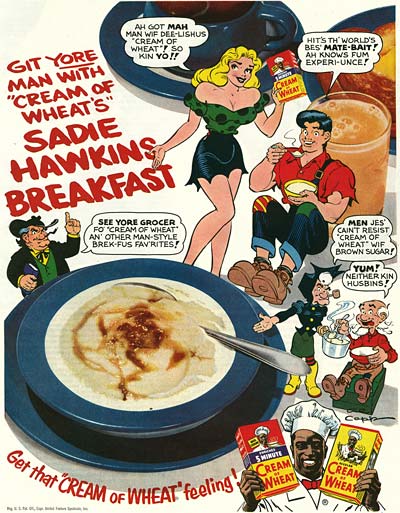

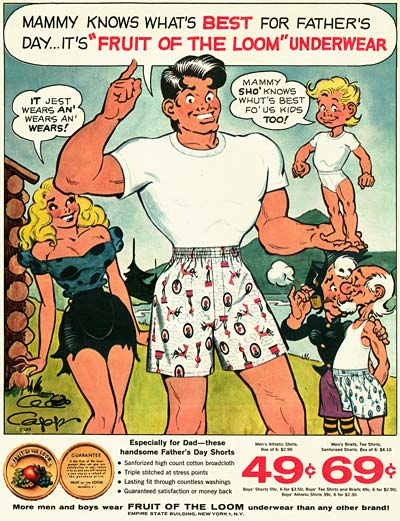

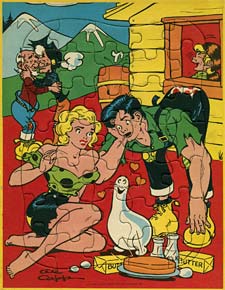

Other artists, like Moe Leff and Bob Lubbers, who drew Long Sam, Capp’s alternate hillbilly comic strip (see above) were tapped to assist as well, especially on the extensive specialty, promotional and licensed commercial work. The Cream Of Wheat and Wildroot Cream Oil magazine ads alone numbered in the hundreds.

Frazetta expert David Winiewicz has described the everyday working mode of operation of Li’l Abner from its golden period:

"By the time Frazetta began working on the strip, the work of producing Li’l Abner was too much for one person. Capp had a group of assistants who he taught to reproduce his distinctive individual style, working under his direct supervision. Actual production of the strip began with a rough layout in pencil done by Al Capp, from Capp’s script or a co-authored script, and the page would pass to Andy Amato and Walter Johnson. Amato would ink the figures, then Johnson added backgrounds and any mechanical objects. Harvey Curtis was responsible for the lettering and also shared inking duties with Amato… In order to make sure that the work stayed true to his style, the final touches would be added by Capp himself. He enjoyed adding a distinctive glint to an eye or an idiosyncratic contortion to a character’s face. The finished strip was truly an ensemble effort, a skillful blending of talents."

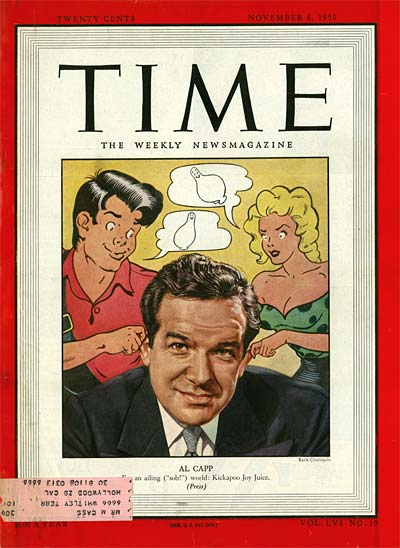

Capp’s latter-day reputation for using assistants is ironic. Nearly every great comic strip artist (with the exception of Charles Schulz) utilized anonymous, behind-the-scenes assistants. But no other cartoonist engineered media coverage of them, complete with photographs, in a major national magazine piece. Capp did, in a November 1950 issue of Time magazine, when he insisted that the article also feature his colleagues Andy Amato and Walter Johnson. Publicizing one’s assistants was unheard of at the time, and is still considered highly irregular. As a direct result, Capp is often remembered today for not having worked on his own strip, a persistent myth that the assistant artists themselves refuted.

The evidence indicates that Capp had the leading hand in the creation of Li’l Abner. Original strips I’ve seen have often included Capp’s pencil doodles on the back. They show his thought process clearly, and are the origin of the material on the other side. Many of Capp’s exploratory sketches survive in just this way, to show that Capp designed the characters carefully and thoughtfully himself.

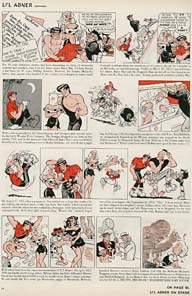

![]() The only time Capp really gave an assistant a free hand visually was in an early (1954) Frazetta-penciled story. Capp was curious to see him bring a fresh look to the daily strip, especially in terms of more lavish and realistic Johnny Comet style inking. Frazetta was also allowed to design a lead villain- a self-caricature, even named "Frankie". (see below) When editors complained about the experimental stylistic departure, the Capp look was reinstated.

The only time Capp really gave an assistant a free hand visually was in an early (1954) Frazetta-penciled story. Capp was curious to see him bring a fresh look to the daily strip, especially in terms of more lavish and realistic Johnny Comet style inking. Frazetta was also allowed to design a lead villain- a self-caricature, even named "Frankie". (see below) When editors complained about the experimental stylistic departure, the Capp look was reinstated.

Capp orchestrated his assistant staff much like an animation director, according to their individual strengths. At the same time, he maintained creative control over every stage of production. Capp himself originated the stories, finalized the dialogue, designed the major characters, rough penciled the preliminary staging and action of each panel, oversaw the finished pencils, and inked the faces and hands of the characters- for 43 years. Yet to this day, Capp’s detractors still falsely claim that Capp "never touched the strip" in an inexplicable ongoing effort to discredit him.

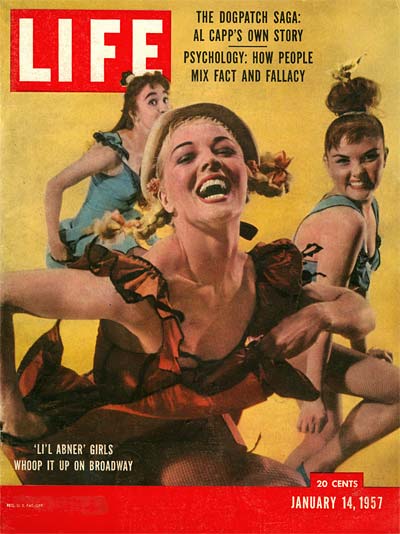

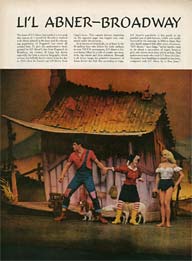

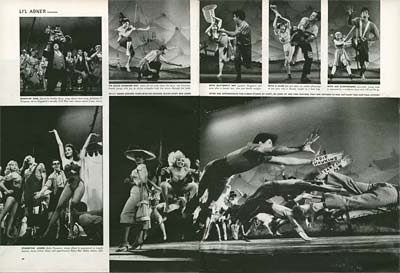

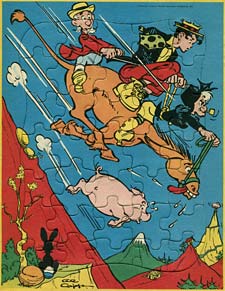

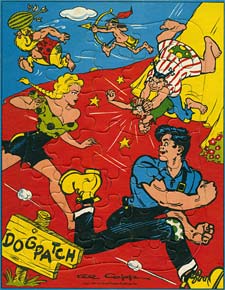

![]() Although a team effort production-wise, few comic strips were as uniquely personal a creation as Li’l Abner. The finished product reflected the singular personality of its creator- Al Capp. As any fool kin plainly see…

Although a team effort production-wise, few comic strips were as uniquely personal a creation as Li’l Abner. The finished product reflected the singular personality of its creator- Al Capp. As any fool kin plainly see…

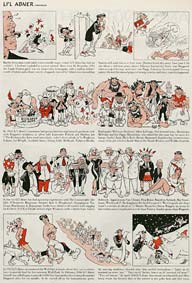

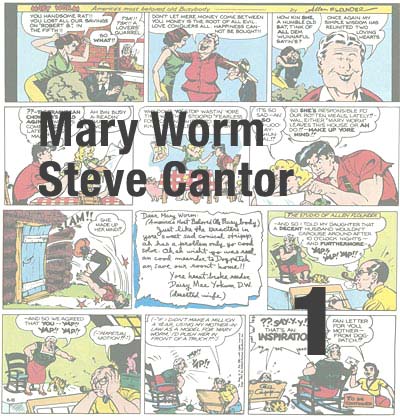

In these two sequences, Capp kids his fellow cartoonists- Mary Worth writer, Allen Saunders and longtime pal Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates, Steve Canyon) The pitch-perfect parody, Steve Cantor was scripted and laid out by Capp, penciled by Frazetta, probably inked by Amato and Johnson, and lettered by an actual assistant at the Caniff studio- probably Frank Engli– it all blends seamlessly to create a truly classic Sunday sequence from 1957…

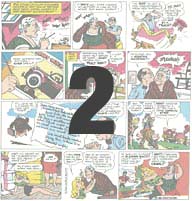

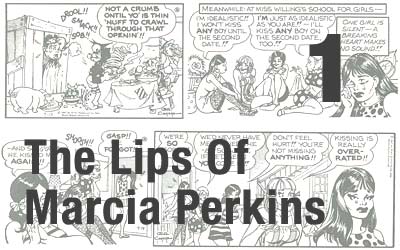

Even in the later years, Capp would occasionally knock one out of the park. The following hilarious continuity appeared in 1967, long after the strip’s nominal heyday. The jaw-dropping Lips Of Marcia Perkins is no less than Capp’s covert, satirical commentary on venereal disease! It could only have gotten past the censors because they didn’t understand it…

TO BE CONTINUED…

Special thanks to my pal, Atlanta-based animator Joe Suggs, for some 9th inning pinch-hit assistance on this article. -Mike Fontanelli, 2008

Many thanks to Mike for this wonderful series of articles.

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit by Mike Fontanelli profiling the career of Al Capp.

![]()

This posting is part of the online Encyclopedia of Cartooning under the subject heading, Newspaper Comics.