Muybridge – Horse Gallop

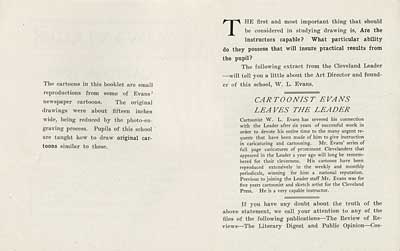

Today I’m going to be showing everyone my planning process for using photographic reference to plan and execute a naturalistic horse run cycle. This process has been used by generations of artists to help analyse and capture the motion patterns of real-world objects and creatures. This type of study is invaluable for building an internal “motion library” in your mind, so that when you have to make guesses about how something impossible might move, those guesses can be as educated as possible. For the beginning animator, doing motion analysis can also help give a stronger sense of what motion details matter, and which are best to remove to get an optimal stylistic motion.

First up, here is the finished animation: Horse_gallop

In a complex cycle like a horse gallop, there are many things to understand, and without experience animating similar creatures it would be difficult to plan ahead for this animation considering that we have so much to keep track of.

Get Video Reference

If you can film your own reference, then that’s a great first step, but if you can’t, the first place I search is the BBC Motion Library at Getty Images. This collection has thousands of real-time and slow-motion shots of sports, nature, vehicles, and much more. It’s free to view and download, which is ideal as we will need to carefully go through our shot frame by frame in order to analyse it.

Here is the shot I used for reference. As stated above, it’s free to download (non-commercial use of course) by right clicking the clip and choosing Save as.

A few notes about the shot:

- It is playing in real-time, not slow motion, so we can use it for timing information

- The shot isn’t stabilized, so we can’t use it to track body parts necessarily

- The whole body is visible, including the feet as they touch the ground

- The speed of the run is relatively stable for a few seconds, ideal for a cycle

Use A Frame by Frame Video Software

Next we need to be able to see each frame of the video one at a time. You can do this by importing the footage into any video editing software if you have it. I prefer to use a much simpler method by opening it in QuickTime.

QuickTime interface

To my knowledge, QuickTime is the only freely available video software which allows you to step through a video one frame at a time (using the left and right arrow keys). Many others allow you to skip several frames, but none that I’ve found allow this level of precision. Another benefit of this software shown above, is the ability to switch the timecode to frames, so we can easily count and locate keyframes in our action.

Before using the shot for any timing information, you’ll need to know the frame rate of the video. I figure this out by going to 1 second in the timecode, the switching to frames to see how many have elapsed. This shot is in a standard 25fps for european PAL broadcast. This will effect our conversion to our frame rate. In my case, I’ll be animating at 24fps (see the conversion math later on at the bottom of my Xsheet).

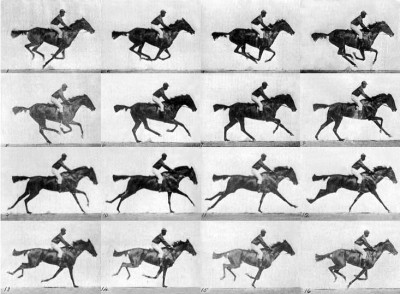

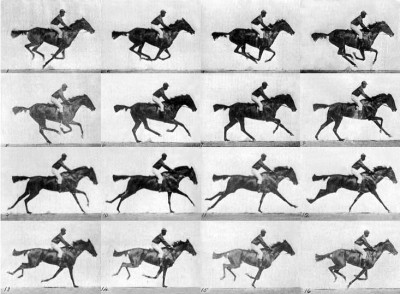

Get Additional Reference

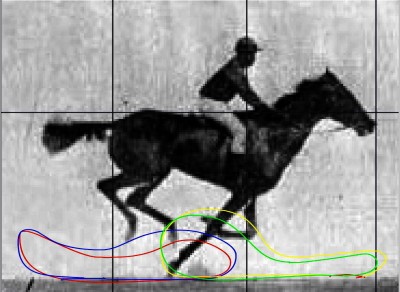

Although we could use a single source of reference, it’s better to have several similar sources to draw from, and the plates from Edward Muybridge’s animal studies have been a source of inspiration to animators for a century. We have an extensive library of Muybridge here. These images (shown at top) are invaluable because they show a flat sideways perspective of a horse galloping with extracted frames to display the entire cycle of motion. The only problem with this is that we don’t know how fast it should be moving, a problem we’ve already addressed with our video reference.

Here is a playback of the muybridge_horse set to a realistic 40fps.

By comparing the frames to our video, I determined that the approximate speed of the original Muybridge shot was a brisk 40fps. I also adjusted the frames to stabilize the ground, put vertical and horizontal lines in to help track key parts of the body, and finally tracked each hoof with a colored ball. All of this information provides almost everything we need to put together our plan.

Horse Gaits

or

or

The last bit of information we need is an understanding of the pattern we hope to find and reproduce. This information I found easily on an equestrian website, along with footfall patterns of all the primary horse locomotion speeds.

Path of feet shown in color code through cycle duration.

Record Observations and Refine

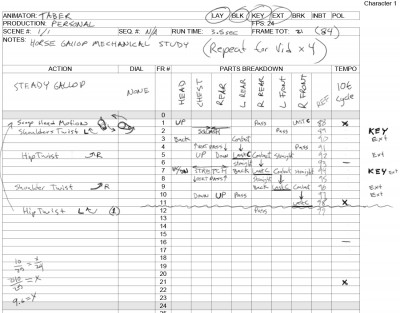

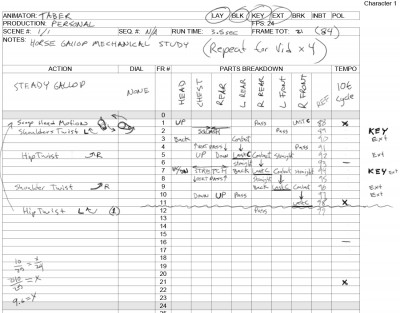

Finally we are ready to utilize all of this information into a formal plan for animating our horse. By stepping through the video and referring to the Muybridge plates, I record all of the pertinent information I can onto an Xsheet.

Modified Xsheet for planning CG animation

By examining the sheet above, you can see that I’ve sought out the most important aspects of the motion and spaced them out in time so that they flow fluidly. Here is a list of the things you should look for before continuing:

- Key Frames – These should be the most informational single images for the action, without which, none of the remaining actions can possibly hope to illustrate the action properly. In my case, I chose the Squashed mid-air position, and the Stretched leaping position of the horse.

- Extremes -The foot contacts must all be present, as well as the maximum and minimum vertical positions of the chest and flank.

- Breakdowns – Wherever necessary, plan for the passing or half-way positions of body parts and poses, so you do not miss the nuance of the motion pattern.

- Small patterns– Note the path and notes about the head, these patterns are important and shouldn’t be missed. Make notes of any details you might easily forget later.

For one reason or another, the use of Xsheets has never fully translated over to computer animation, which I think is a major loss. Although these sheets were originally used to plan for the exposure of cell levels in traditional animation, they can find a valuable second life in helping to plan body part motions and musical timing.

Execute Plan

With all of this preparatory work, the only thing left to do is to use this roadmap to complete your animation. By this point, you should have such a solid idea of what your animation is going to look like, that the actual work of animation is almost an afterthought. In The Illusion of Life, as well as The Animator’s Survival Kit, the authors tell stories of their lengthy and strenuous planning procedures, and how once planned out, an animation scene was practically complete before pencil ever touched page. This method allows you to keep a solid focus on your scene even between work sessions, and frees you to focus on the details without becoming lost in the larger patterns of motion.

Taber Dunipace

Director of Membership

tdunipace@animationresources.org

by

by

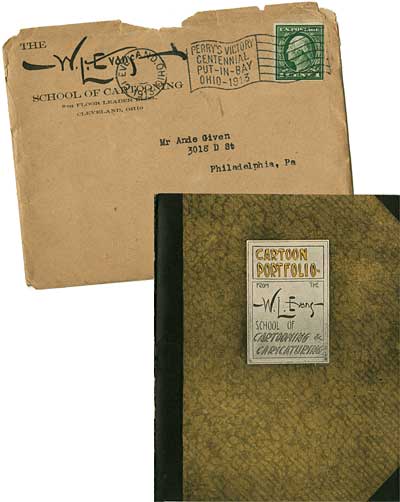

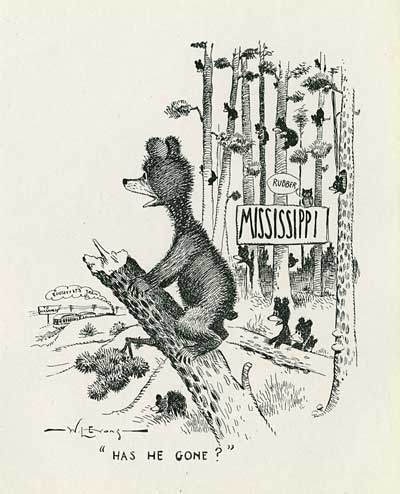

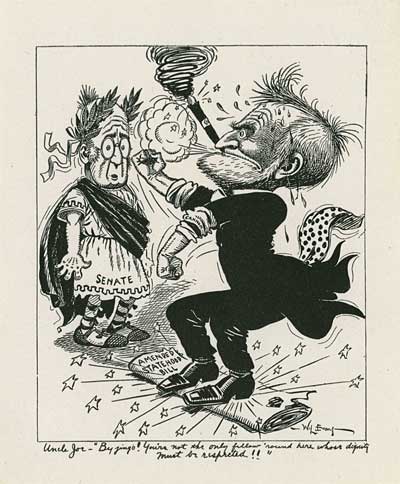

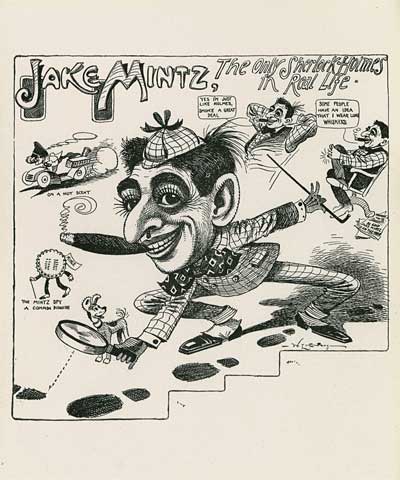

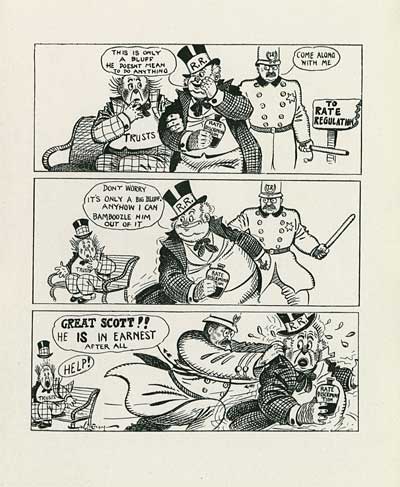

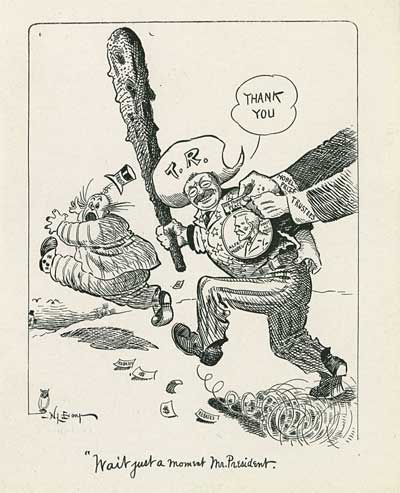

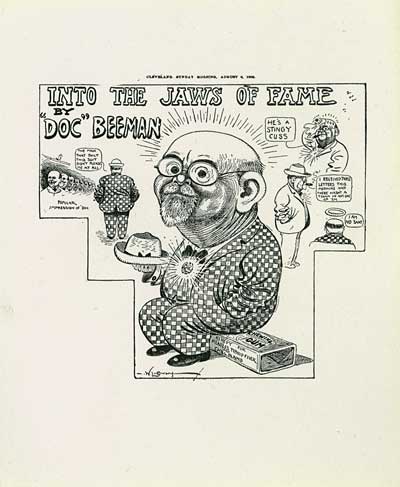

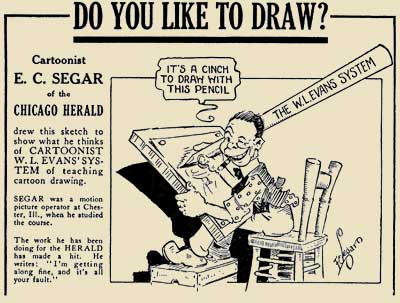

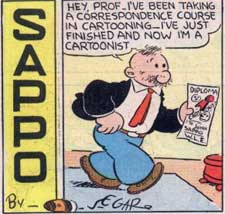

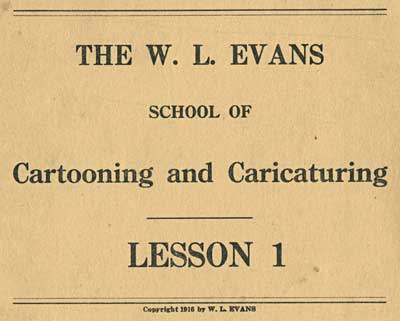

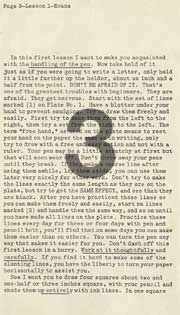

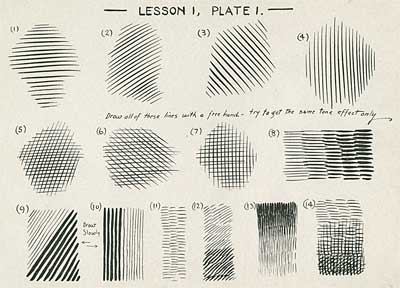

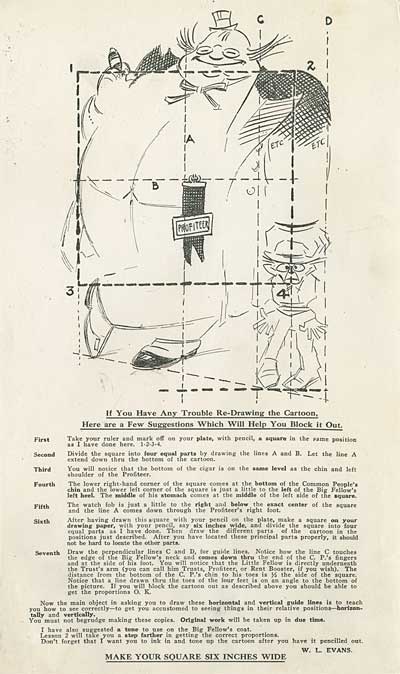

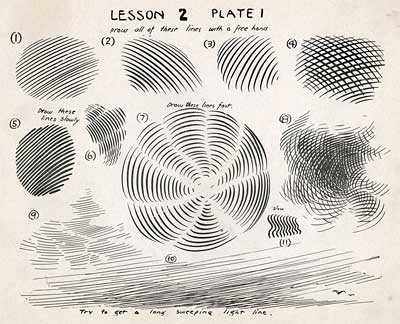

![]() Decades later, Segar made mention of his early education in his strip, Thimble Theater. In 1934, his character, Sappo took the W. L. Evans Cartooning Course and delighted readers with cartoon drawings made from letters of the alphabet. Segar wasn’t the only cartoonist who got his start with this course. Chester Gould of Dick Tracy fame was a graduate of the W. L. Evans course, as was Dennis the Menace creator, Hank Ketcham.

Decades later, Segar made mention of his early education in his strip, Thimble Theater. In 1934, his character, Sappo took the W. L. Evans Cartooning Course and delighted readers with cartoon drawings made from letters of the alphabet. Segar wasn’t the only cartoonist who got his start with this course. Chester Gould of Dick Tracy fame was a graduate of the W. L. Evans course, as was Dennis the Menace creator, Hank Ketcham.

![]() STUDENT MEMBERSHIP

STUDENT MEMBERSHIP![]()