Woolie Reitherman, Bill Peet, Ken Andersen and

Ham Luske tussle during a story meeting for

"101 Dalmatians" (via Michael Sporn’s Splog.)

When we left off last time in our series on cartoon writing, the gag sessions had led to the establishment of an overall structure and continuity. The random threads of ideas had meshed into the framework of a story with a beginning, middle and end. Today, we are going to look at how that bare skeleton outline was fleshed out for the first time in rough storyboard form. But first, a little bit about the relationship between the story men and the rest of the animation staff…

In the photo above, you see story man Bill Peet rough-housing with designer Ken Anderson and directors Woolie Reitherman and Ham Luske. Unlike today, when a cartoon scriptwriter rarely if ever ventures into the artists’ domain, golden age cartoon writers interfaced with a large chunk of the animation staff on a daily basis. As we discussed in the first couple of articles in this series, animators were on hand at all story meetings to suggest sequences of action that would lend themselves to funny animation. But at Disney, the influence of the animation staff on the story went even further than that…

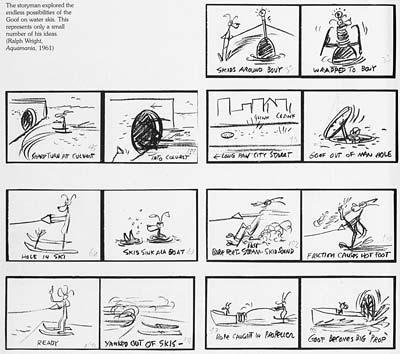

INSPIRATIONAL ART

Disney employed a special crew of artists whose sole duty was to visualize the ideas being tossed out for consideration during the story meetings. They established the key setups in the film. The drawing above is a very early inspiration sketch from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was drawn by one of Disney’s greatest concept artists, Albert Hurter. At the time this sketch was created, the character designs hadn’t yet been finalized, however Hurter was called upon to determine the best way to stage the scene. If you compare this sketch to the scene as it appears in the film, you’ll see how closely Hurter’s background details were followed by the layout department.

Hurter’s drawings acted as “setups” for many of the scenes in Snow White. They established the space the characters inhabited clearly, so the storyboard artists didn’t create the space randomly one scene at a time. For example, compare the Dwarfs’ cottage or Roger and Anita’s living room in 101 Dalmatians to the house in Tom & Jerry cartoons. The individual shots in the Disney cartoons all fit within a specific space, while in many of the Tom & Jerry cartoons, the house is just a random assemblage of baseboards, potted plants and pictures hanging on the walls. Nailing down the setups before the storyboard is done helps the artist envision the space from different angles.

Concept artists would also experiment with the overall design approach. In the "Dance of the Hours" sequence from Fantasia, it was decided to contrast different design motifs for each of the various times of day… the morning section consisted of static horizontal and vertical lines, the afternoon was made up of ellipses, the evening was represented by S curves, and in the example above by James Bodrero from the night sequence, zig zags predominated.

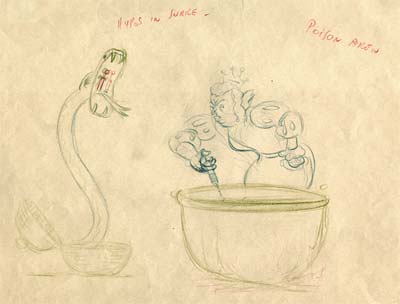

As the story progressed, the cast of characters would come into focus. Artists would be assigned to establish and refine the way each of the characters looked. This example is a design by Grim Natwick for an unmade Silly Symphony based on the Aesop’s Fable, "The Three Musicians of Bremen". Joe Grant was charged with the task of creating a character design department at Disney. His crew would establish the design of the characters and provide the artists with model sheets of the characters in various attitudes and from various angles.

All of the designs from the conceptual artists would filter back to the story department, where they were pinned up on the boards and incorporated into the story sketches as the project progressed. I’ll have more on that in the next article in this series.

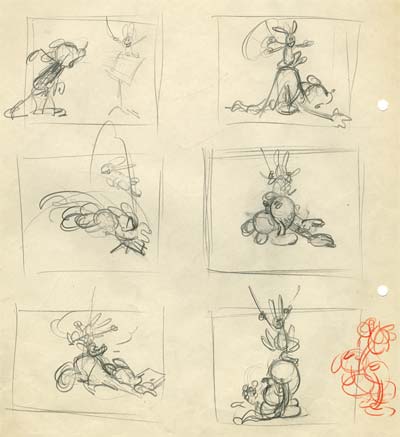

THE ROUGH STORYBOARD

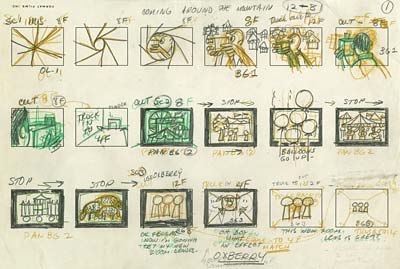

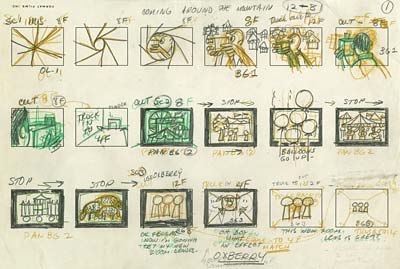

The technique of drawing out stories in sketches goes back to the earliest days of animation. It probably evolved out of newspaper comics. Here we have a thumbnail storyboard from around 1927 by Grim Natwick from Bill Nolan’s Krazy Kat studio. Unlike most storyboards, this one reads top to bottom instead of left to right.

The basic story of this board is as follows…

Krazy Kat is spending a quiet evening at home with his wife, who is listening to the radio. Krazy sneaks away to call his girlfriend and crawls into the phone and through the wires to meet her at the "Flaming Youth" nightclub. They dance to the music of the hot jazz band, and as the tempo speeds up, the whole room joins in a wild dancing frenzy. Krazy begins swinging his girlfriend around the dance floor. It is revealed that the music is being broadcast on the radio and Krazy’s wife is listening in. The station announcer mentions that Krazy Kat is on the dance floor, and the wife stomps down to the nightclub to confront him. Just as the song reaches its climax, the wife enters and bops Krazy over the head with a bass fiddle.

Grim told me that the earliest form of storyboard he ever saw was at Hearst’s International Film Service studio. The director, Gregory LaCava would doodle out the story in rough thumbnail form straight ahead as a comic strip. Then he would mark the scene cuts, assign an approximate length to each scene, and take a pair of scissors and cut the panels up into sequences to hand out to the animators. This technique probably had its origins even earlier at the Raoul Barre studio, where LaCava trained to animate. The interesting thing about the Krazy Kat storyboard pictured above is that by 1927, the technique was well enough established that stock storyboard paper was printed up with the boxes ready to be filled in.

In the early 30s at Disney, the technique was perfected by Webb Smith, who suggested drawing the panels on individual sheets of paper and pinning them up on cork boards. This made it simple to insert or delete panels, and allowed the storyboard artist to see the visual flow of an entire sequence at once.

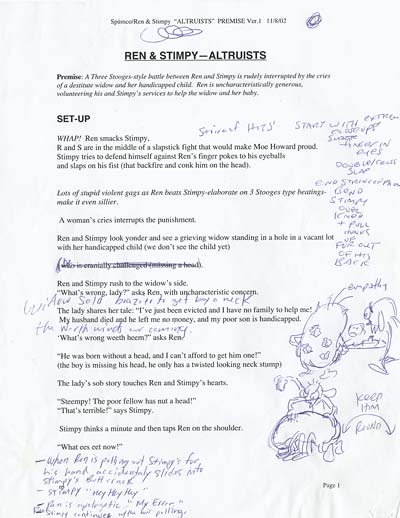

At Disney, the boards evolved as the sequences developed, but at Warner Bros, there were two iterations of storyboards for each cartoon- the first draft thumbnail board and the final director’s board. The thumbnail board was the storyboard artist’s first pass at the story. He was free to work out the basic gags, staging and cutting, without having to deal with drawing the poses “on model” or putting a lot of detail into the backgrounds. At this stage, dialogue was just a general suggestion- it wasn’t locked down until the director had input on the board. That way the dialogue would be a natural outgrowth of the action, instead of the action being driven by the dialogue.

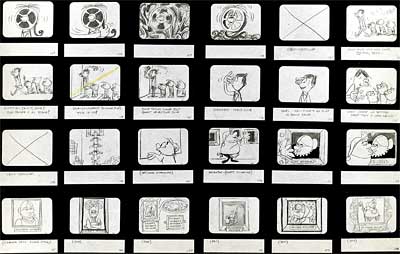

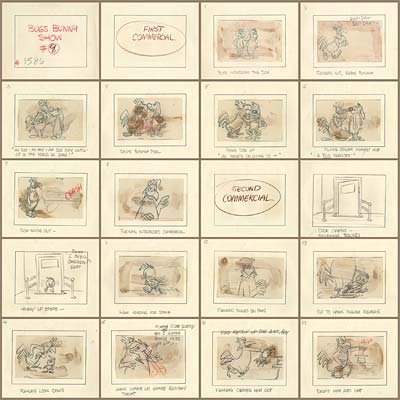

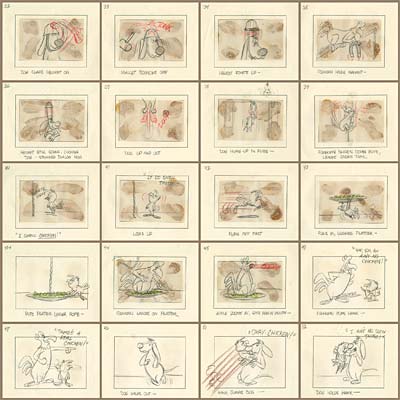

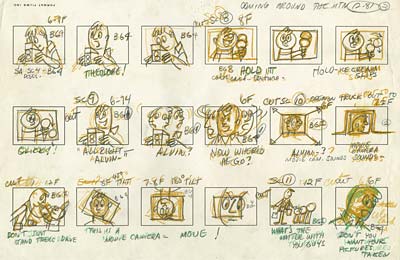

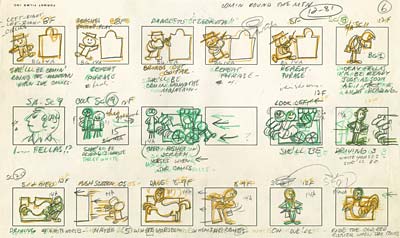

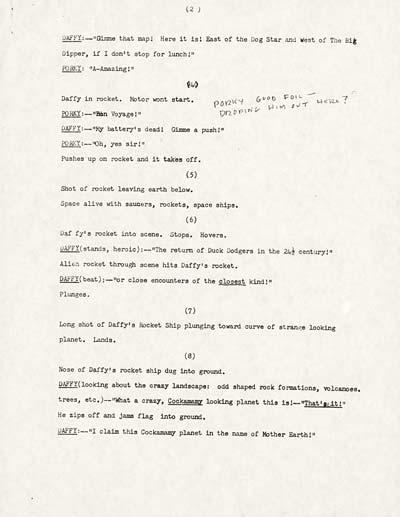

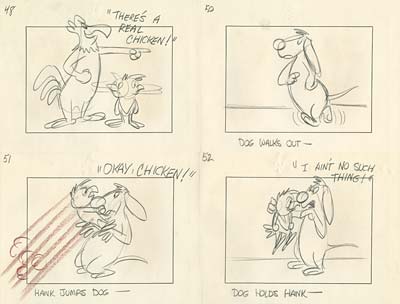

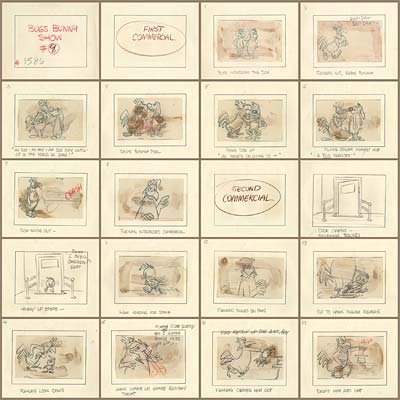

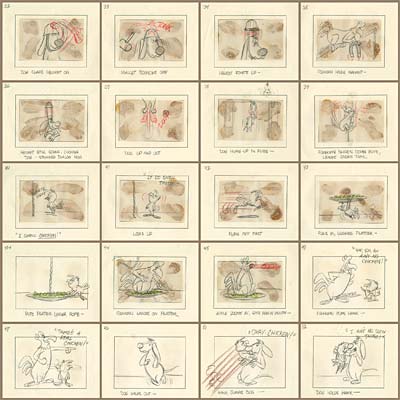

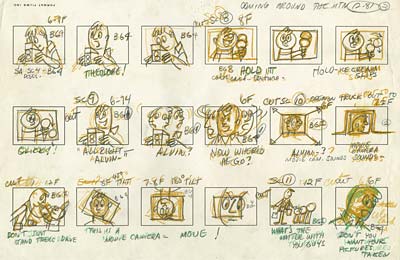

Here is an example of a thumbnail board by John Dunn from the Bugs Bunny Show (1960)…

There are a couple of interesting things we can deduce from this board. It appears that the panels with the glue stains were boarded first. They probably represent Dunn’s first thoughts on gags for the story. He then went back and expanded the introductions to the sequences and the transitions in and out of the commercials. Dialogue for some sections is indicated by placeholders. (ie: "Foghorn introduces commercial.", "Foghorn cons hawk.") These lines would be written once the action of the cartoon was all approved. At this stage, only the dialogue needed to sell the gag was necessary, and even that could change as the board developed. The end of this board is quite choppy. It’s likely that more development was done on the final gags before the board was ready to go into production. At this early stage, the scene numbering for production tracking had not yet been established. Scene cuts might still be moved or eliminated as the board evolved. So the numbering on the panels is simply a page number to keep the drawings in order.

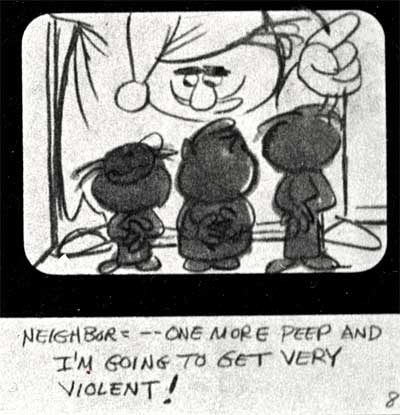

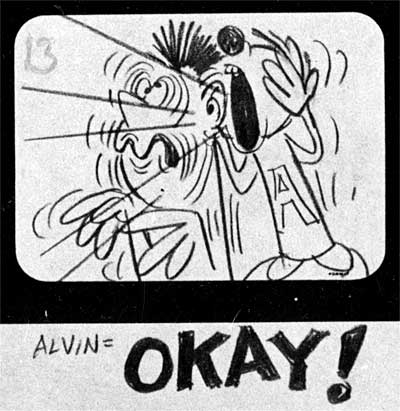

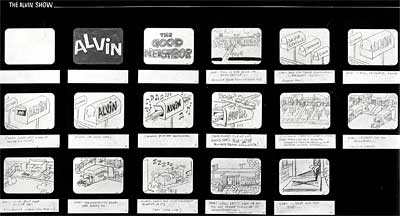

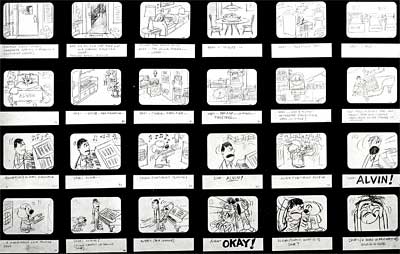

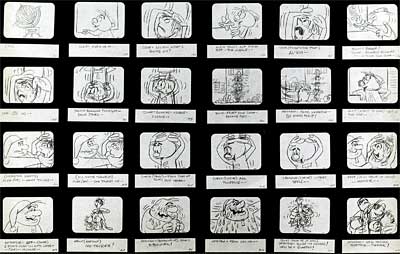

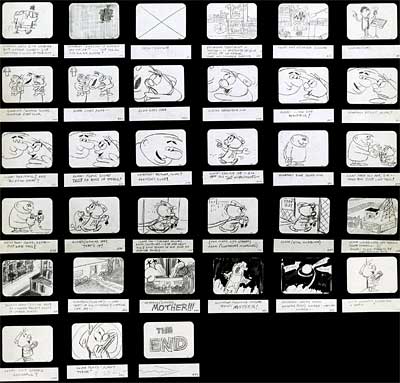

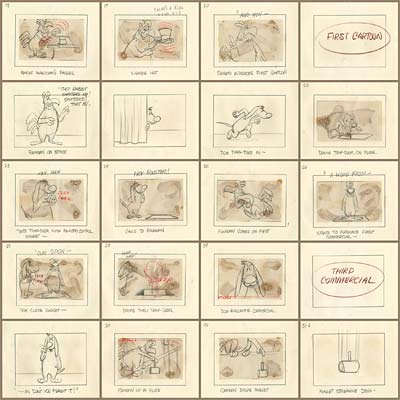

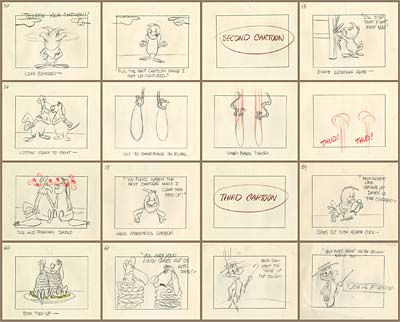

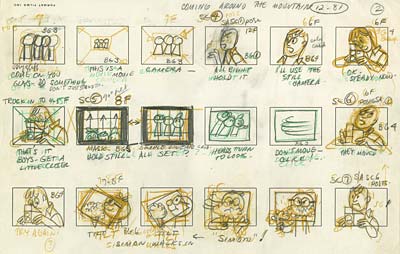

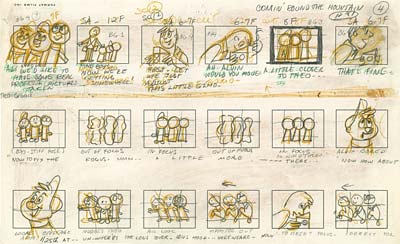

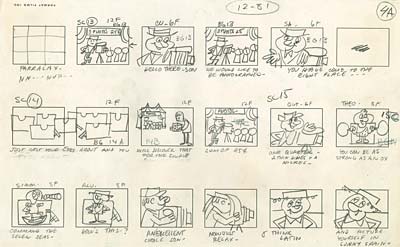

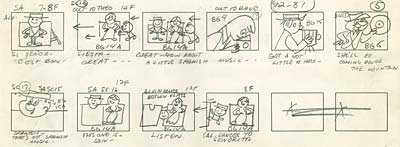

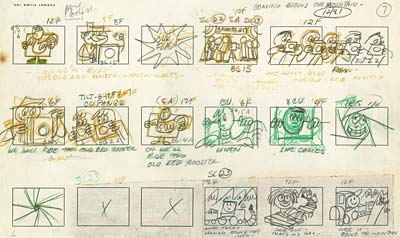

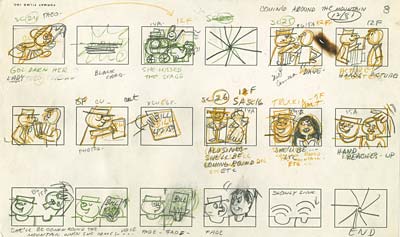

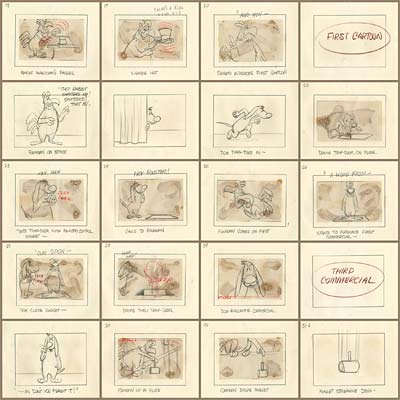

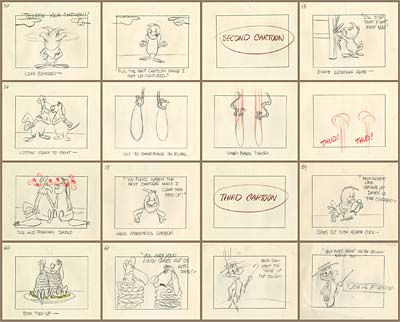

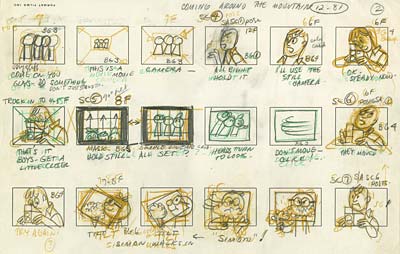

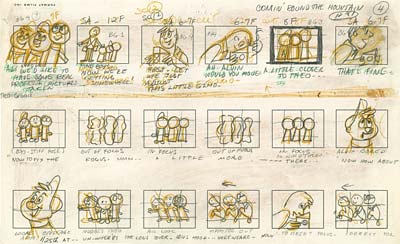

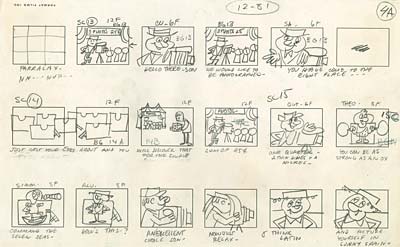

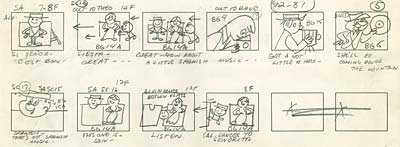

Here is an example of a thumbnail board from Format Films’ The Alvin Show…

Bob Kurtz was a story man at Format, and he tells me that this board was most likely drawn by one of the directors as a quick reference to help him organize the scenes. Notice how he juggles different sorts of shots to create a visual rhythm. The animation on this show was extremely limited, so contrasts in design were needed to make up for it…

It appears that page five required some revision, but the pre-printed paper made it difficult to juggle the order and number of panels. The artist was forced to completely redraw every panel on the page, wasting time and losing some of the spark of life in his thumbnails in the process. Also note the pasteover at the bottom of page seven and the numerous erasures throughout the board.

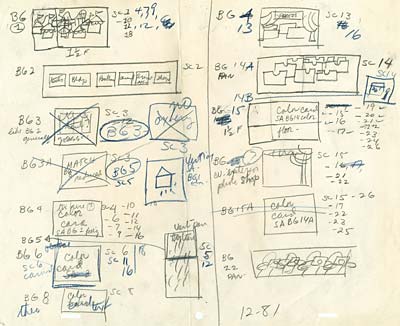

This particular board has an interesting last page. The Director planned out the shots very carefully to allow background paintings to be reused in multiple shots. This saved money and allowed the background painters more time to paint the establishing shots. Very clever!

Sometime in the early 1960s, the technique of storyboarding took a huge step backwards. Instead of using Webb Smith’s more flexible cork board and push pin system, story artists went back to drawing out the action on stock printed paper with three to six boxes printed on it. This made it difficult to insert or delete panels. Why did they abandon a system that worked well for one that didn’t?

The next article in this series will deal with the pitch…

Stephen Worth

Director

Animation Resources

This posting is part of an online series of articles dealing with Instruction.

by

by