Every other month, members of Animation Resources are given access to an exclusive Members Only Reference Pack. In May 2016, they were able to download this collection of WWI cartoons by Louis Raemaekers. Our Reference Packs change every two months, so if you weren’t a member back then, you missed out on it. But you can still buy a copy of this great e-book in our E-Book and Video Store. Our downloadable PDF files are packed with high resolution images on a variety of educational subjects, and we also offer rare animated cartoons from the collection of Animation Resources as downloadable DVD quality video files. If you aren’t a member yet, please consider JOINING ANIMATION RESOURCES. It’s well worth it.

PDF E-BOOK:

Raemaekers Cartoons![]()

Land and Water Edition Volume One

This e-book faithfully reproduced the first volume of The Land and Water Edition of Raemaekers Cartoons. It is set up ready to be printed double sided on two sided 8 1/2″ by 11″ punched paper, and is optimized for viewing on iPads with retina screens.

REFPACK010: Raemaekers Cartoons![]()

Adobe PDF File / 331 Pages

457 MB Download

Berntstorff- The Next To Be Kicked Out

(1869-1956)

“The cartoons of Louis Raemaekers constitute the most powerful of the honorable contributions made by neutrals to the cause of civilization in the World War.” -Theodore Roosevelt, 1917

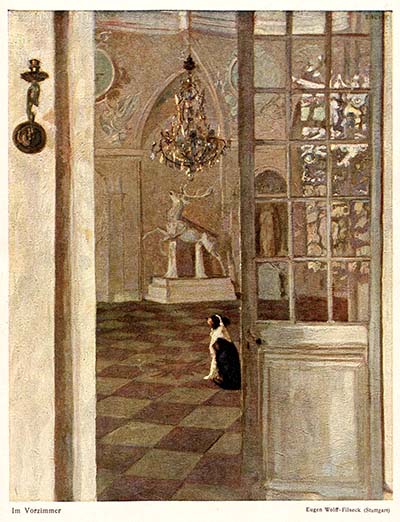

![]() Louis Raemaekers was born in the Netherlands in 1869. He led a quiet life, painting landscapes while studying and teaching in Amsterdam and Brussels. In 1906 he was asked by a newspaper in Amsterdam, Het Handelsblad, to produce a series of cartoons. His initial attempt at a comic strip was a complete failure, so he turned to politics.

Louis Raemaekers was born in the Netherlands in 1869. He led a quiet life, painting landscapes while studying and teaching in Amsterdam and Brussels. In 1906 he was asked by a newspaper in Amsterdam, Het Handelsblad, to produce a series of cartoons. His initial attempt at a comic strip was a complete failure, so he turned to politics.

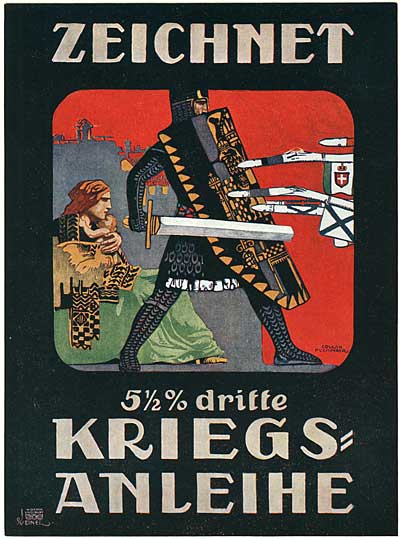

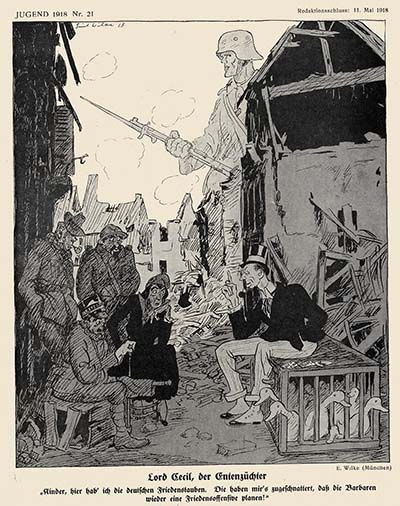

Raemaekers’ interest in international affairs led him to speak out about German ambitions for expanding their territory into Holland and the Allsace region of France. This got him into trouble with the editors of Het Handelsblad. The Netherlands was neutral and Germanic aggression was a hot issue, so they started cutting back on the number of cartoons by Raemaekers in their pages. When a rival paper, De Telegraaf offered him more editorial freedom and as much space as he could fill, he jumped at the chance.

“I was in prison for life, but they found I had many abilities for bringing civilization to our neighbors, so now I am a soldier.”

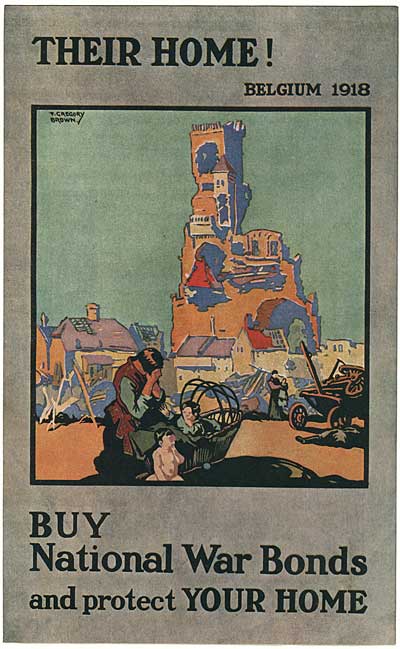

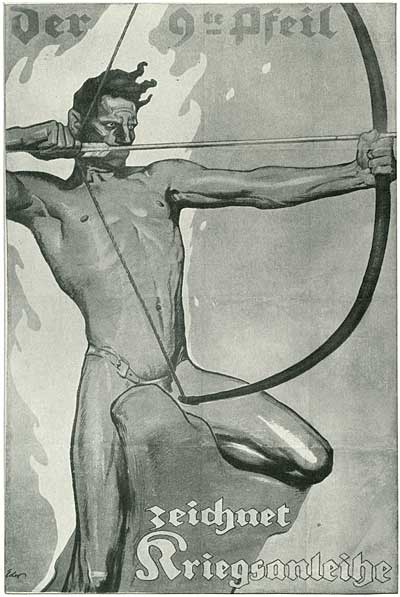

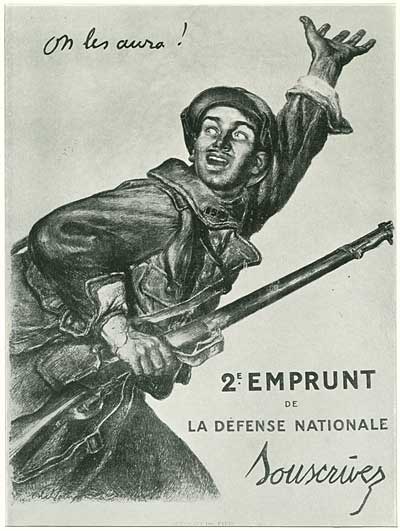

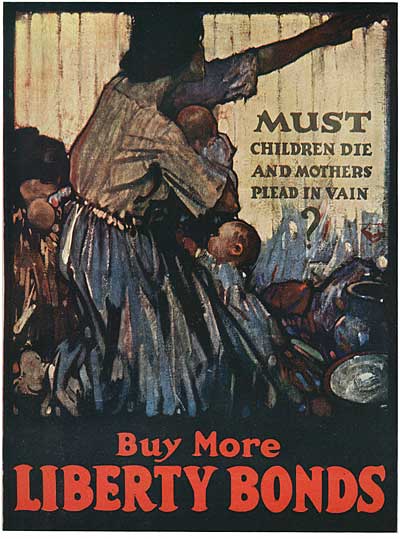

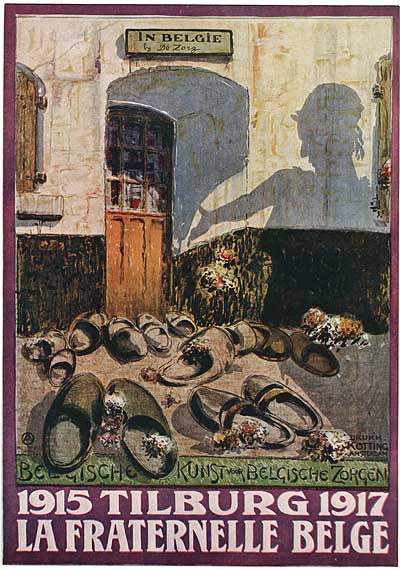

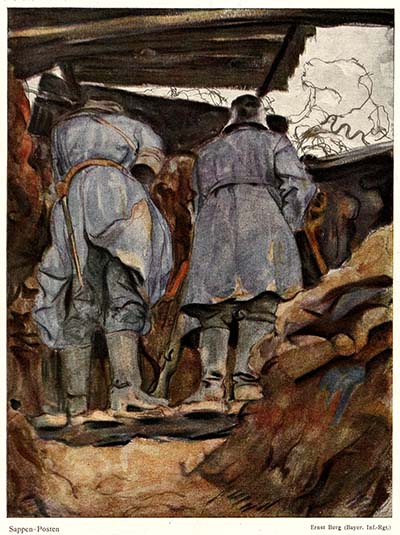

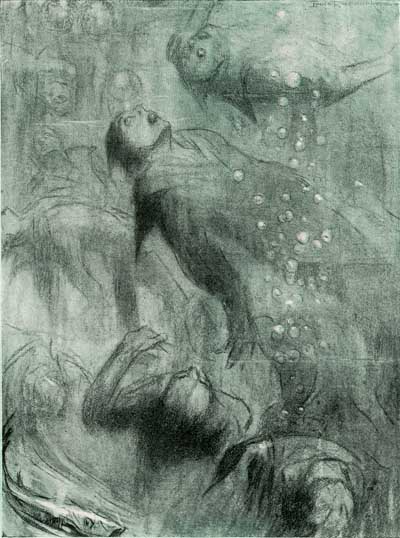

At the beginning of the First World War, Germany invaded Belgium. The Netherlands was neutral, so refugees streamed across the border. With them, they carried stories of German atrocities against the Belgian people. Raemaekers secretly crossed the border into Belgium to see for himself if the stories were true and returned outraged at what he had witnessed. He began to produce fiercely Anti-German political cartoons that burned with the passion of personal conviction.

The Massacre of the Innocents in Belgium

“All in good order. Men to the right, women to the left.”

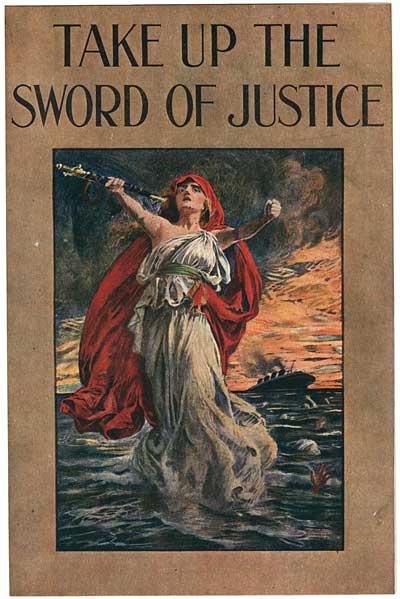

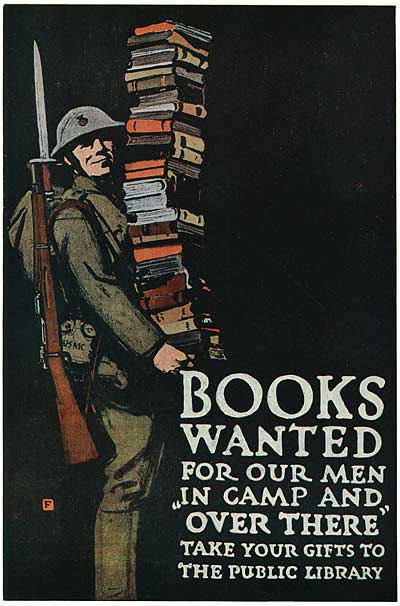

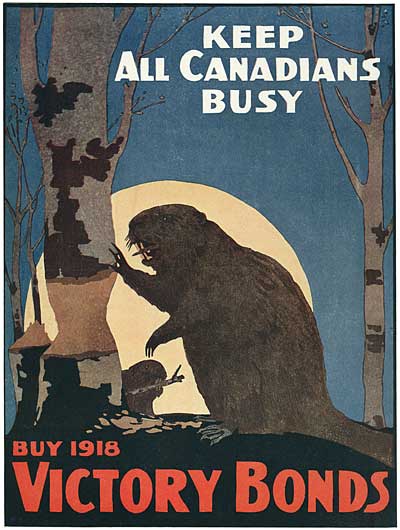

Raemaekers’ cartoons were picked up for distribution by the British government in a series of propaganda pamphlets. The campaign was so effective, the Germans used their influence in the Netherlands to have Raemaekers tried for “endangering Dutch neutrality”. The charges were eventually dropped, but Kaiser Wilhelm II put a bounty of 12,000 marks on his head. When his wife began to receive anonymous threats, Raemaekers realized that his family was in great danger. He relocated to England, where his cartoons were celebrated in books and museum exhibitions, and syndicated to newspapers across France, Canada and the United States.

The German Tango- “From East to West

and West to East, I dance with thee.”

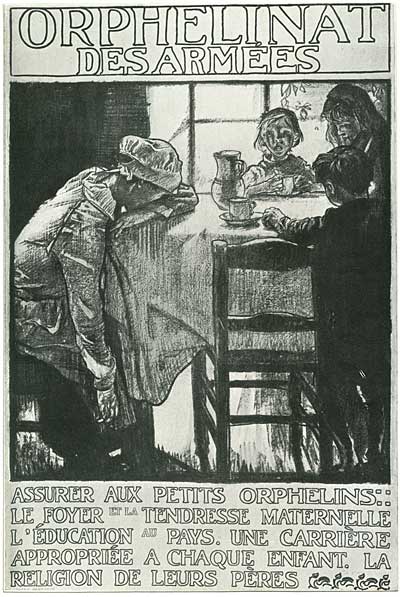

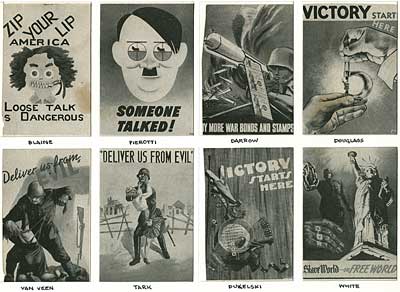

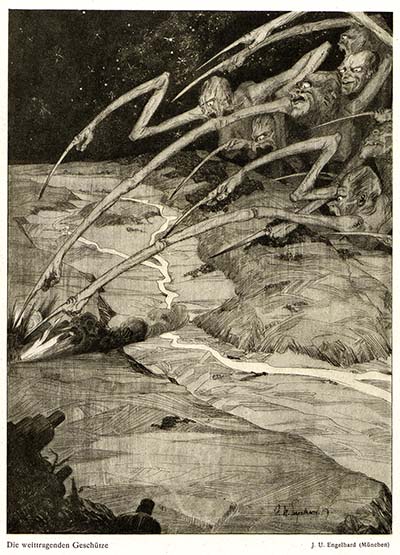

Raemaekers cartoons were instrumental in fighting against deeply entrenched American isolationism, and in 1917 the United States entered the war. Raemaekers quickly organized a lecture tour of the US and Canada, rallying the allies to support the French and mobilize against the Germans. The Christian Science Monitor said of Raemaekers, “From the outset his works revealed something more than the humorous or ironical power of the caricaturist; they showed that behind the mere pictorial comment on the war was a man who thought and wrought with a deep and uncompromising conviction as to right and wrong.”

Von Bethmann-Hollweg And Truth

“Truth is on the path and nothing will stay her.”

MEMBERS LOGIN To Download E-Book

JOIN TODAY To Access Members Only Content

After the war, Raemaekers withdrew from international affairs, spending the last 25 years of his life quietly in France and Brussels. By the time he passed away in 1956, the world had pretty much forgotten him. But in his obituary, the New York Times summed up his career, saying, “It has been said of Raemaekers that he was the one private individual who exercised a real and great influence on the course of the 1914-18 War. There were a dozen or so people (emperors, kings, statesmen, and commanders-in-chief) who obviously, and notoriously, shaped policies and guided events. Outside that circle of the great, Louis Raemaekers stands conspicuous as the one man who, without any assistance of title or office, indubitably swayed the destinies of peoples.”

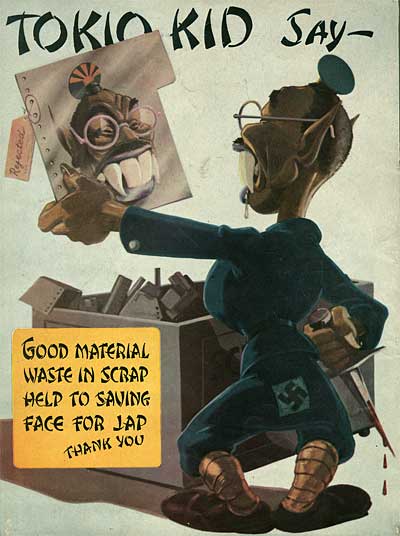

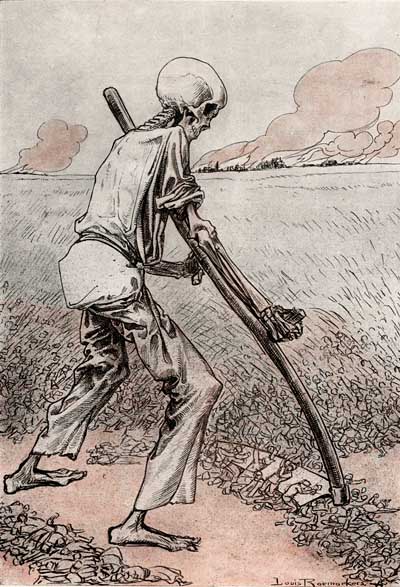

The Harvest Is Ripe

Today, Raemaekers is remembered more by students of the First World War than by cartoonists and artists. His work has been looked down upon with scorn by certain revisionist historians who argue that some of the more extreme atrocities depicted in Raemaekers’ cartoons never took place. It is always difficult in wartime to know what is happening behind enemy lines. Although Raemakers made several clandestine research trips to Belgium during the war, he also depended on second hand accounts, some of which have since been proven to be untrue. But no one denies that Raemaekers himself believed his cartoons to be completely factual.

A Fact- The brutalization by Major Tille of the German Army on a small boy of Maastricht was verified by an eye-witness.

This sincerity is what makes him important to cartoonists today. He deserves to be remembered, not as just a propagandist, but as an artist who stood up for what he believed. His passion carried him from being a provincial landscape painter to becoming one of the most powerful and influential individuals on the world stage. There is tremendous power in the art of cartooning. It’s not just “ducks and rabbits” and mindless children’s entertainment. It can change the world. No cartoonists should ever forget that.

The Future- “For freedom’s battle once begun,

though baffled oft, is ever won.”

For more detailed information on Louis Raemaekers’ life and career, see John Adcock’s excellent article at Yesterday’s Papers.

The Sea Mine- Von Terpitz’s Victims

This posting is part of the online Encyclopedia of Cartooning under the subject heading, Editorial Cartoons.

![]()

This posting is part of a series of articles comprising an online exhibit entitled Theory.

THIS IS JUST THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG!

Animation Resources has been sharing treasures from the Animation Archive with its members for over a decade. Every other month, our members get access to a downloadable Reference Pack, full of information, inspiration and animation. The RefPacks consist of e-books jam packed with high resolution scans of great art, still framable animated films from around the world, documentaries, podcasts, seminars and MORE! The best part is that all of this material has been selected and curated by our Board of professionals to aid you in your self study. Our goal is to help you be a greater artist. Why wouldn’t you want to be a member of a group like that?

Membership comes in three levels. General Members get access to a bi-monthly Reference Pack as well as a Bonus RefPack from past offerings in the in-between months. We offer a discounted Student Membership for full time students and educators. And if you want to try out being a member, there is a Quarterly Membership that runs for three months.

JOIN TODAY!

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

FREE SAMPLES!

Not Convinced Yet? Check out this SAMPLE REFERENCE PACK! It will give you a taste of what Animation Resources members get to download every other month! That’s 560 pages of great high resolution images and nearly an hour of rare animation available to everyone to download for FREE! https://animationresources.org/join-us-sample-reference-pack/

![]()

![]() Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.