I’m going to chat for a minute about some of our work in progress at Animation Resources…

The other day, I was talking with a friend about what was important about what we do at the Animation Archive, and he said that the collection was the most important thing. We’ve amassed a huge archive of digitized films and scanned artwork. But I disagreed. Google search has a massive collection too, as does archive.org. The thing that sets us apart is CURATION.

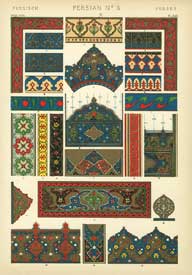

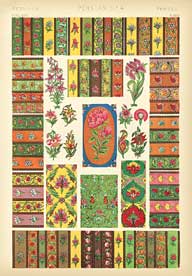

You can have all the treasures in the world, but if you aren’t putting them into context, they’re just specimens in jars of formaldehyde sitting on a dusty shelf. Great objects exist all over. Museums and warehouses are full of them. The trick is to put them to use for a purpose. That takes a deeper understanding. With every Reference Pack and article we share with our followers, Animation Resources is encouraging and supporting our members to engage in that sort of self study and application of principles.

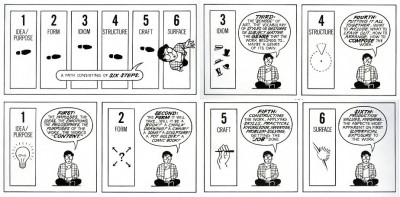

The job of Animation Resources is to bring “the good stuff” to working artists, so they can analyze it, process it, and apply the fundamentals they uncover to their own work. Learning to be creative is a process like any other constructive process, but a lot of artists have never stopped to think of how they go about it. I was chatting with a great artist about this once, and he swore up and down that creativity couldn’t be learned, either you have it or you don’t. I started listing off the ways that you foster and develop creativity. As I listed them, he replied, “I do that.” “I do that.” “I do that.” He thought he had been born creative, but he was actually born doing the things that make a person creative. He was working to become more creative without even knowing it.

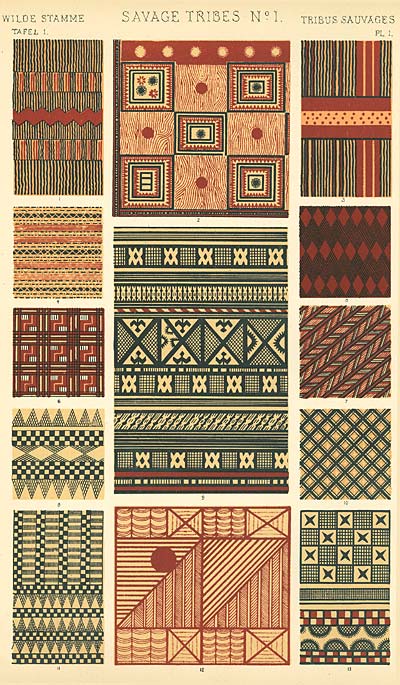

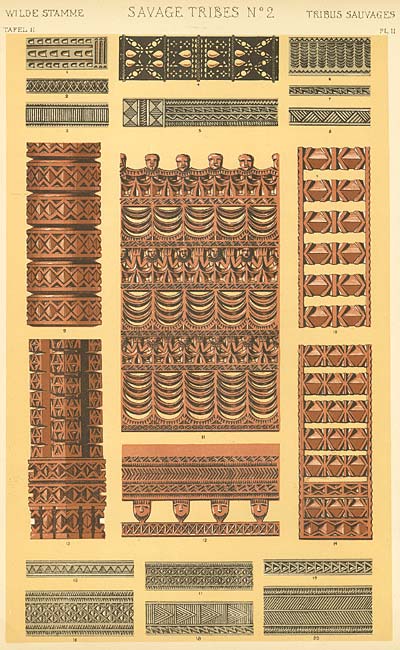

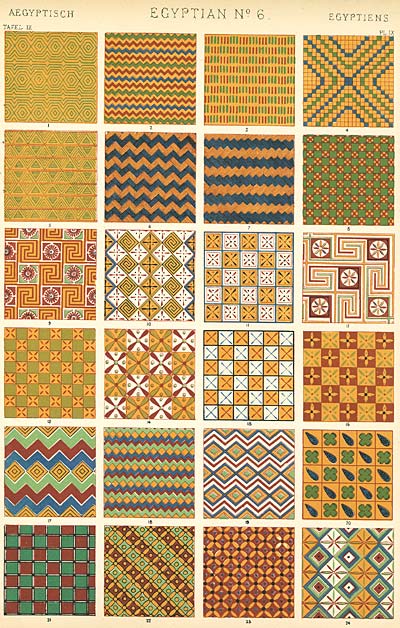

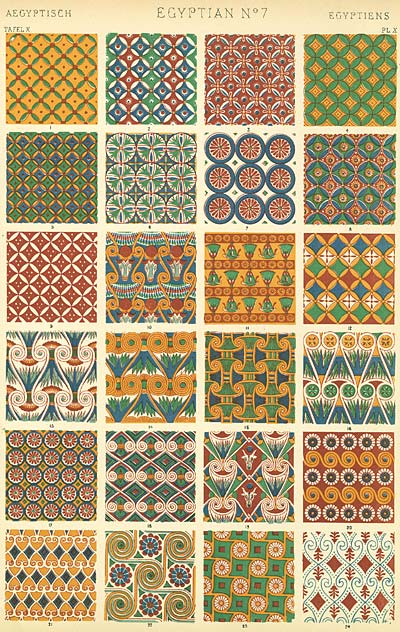

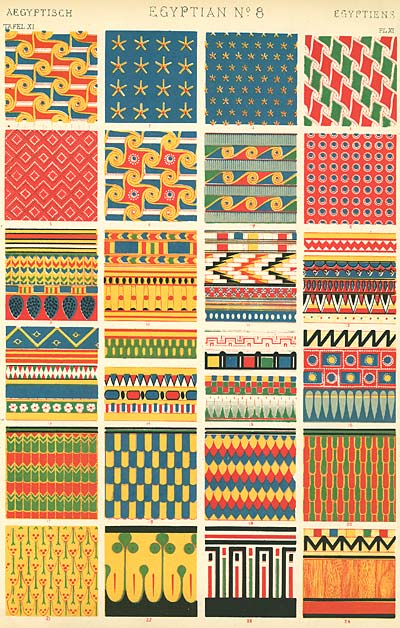

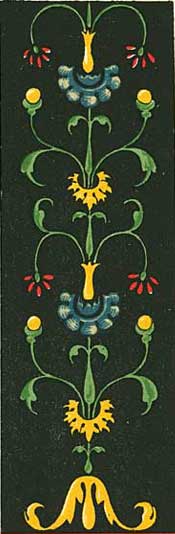

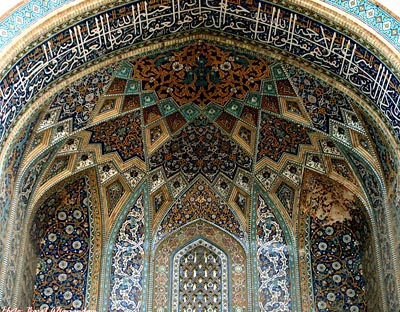

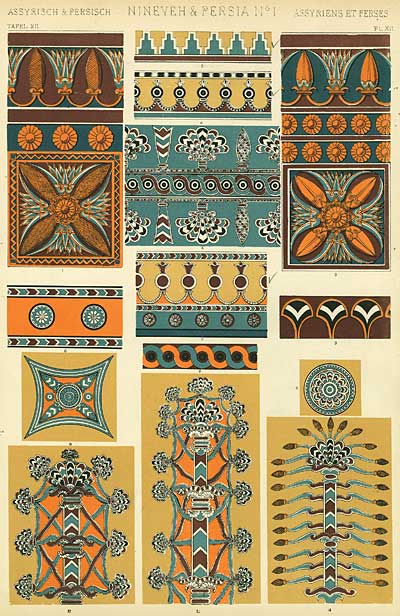

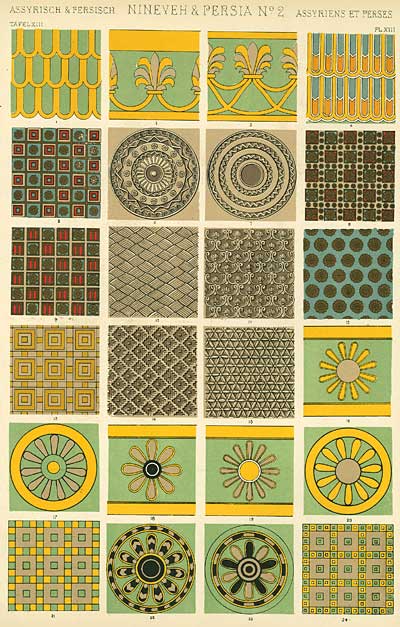

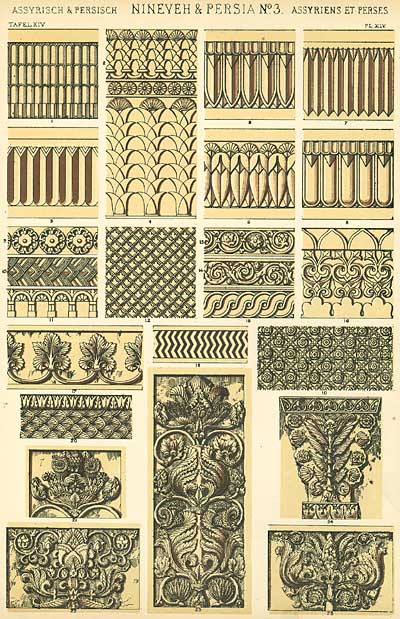

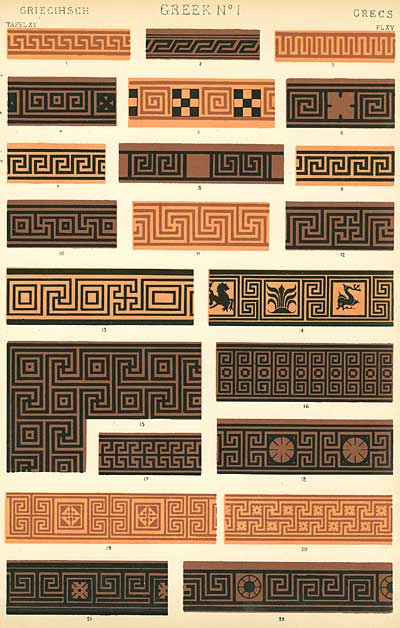

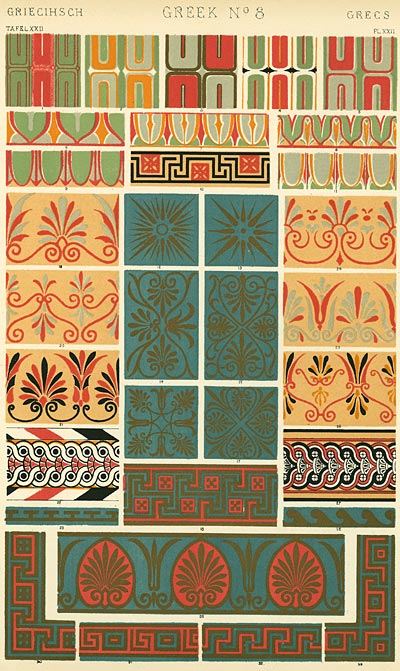

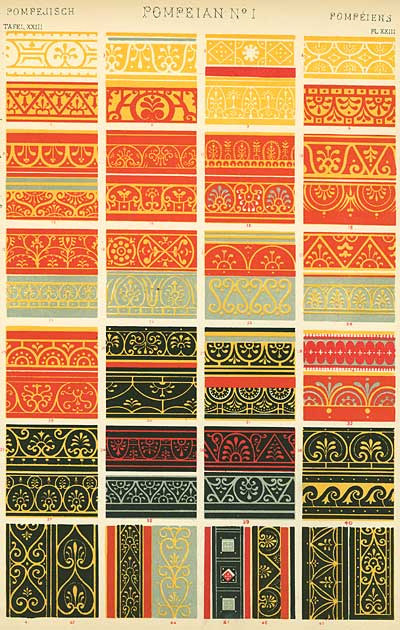

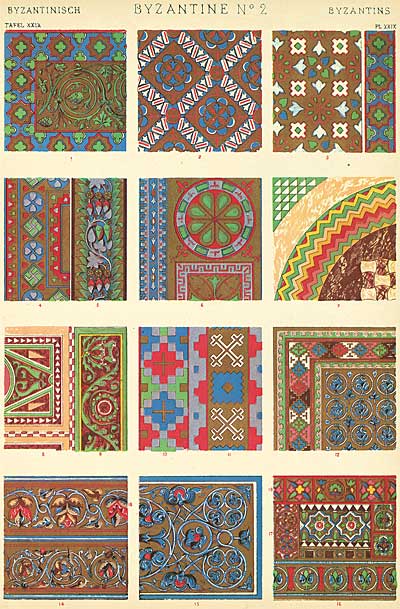

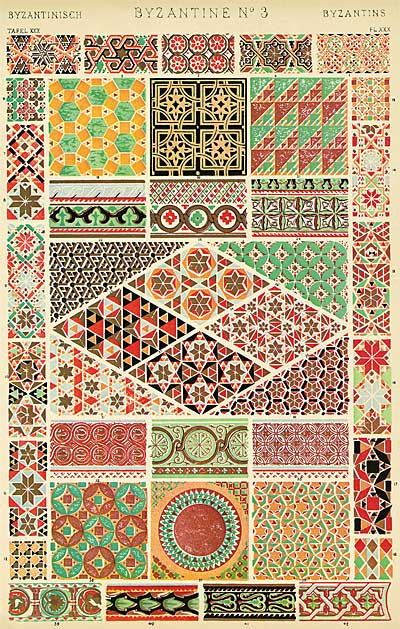

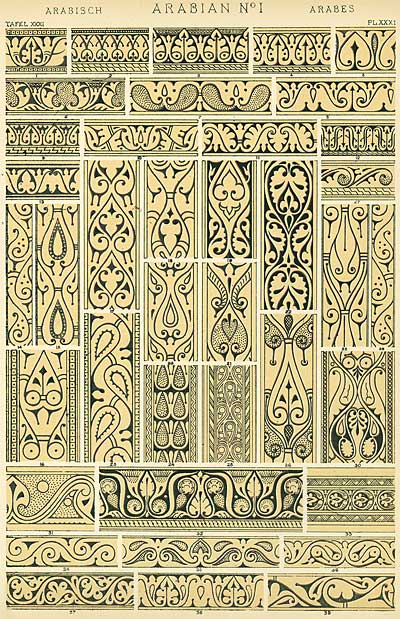

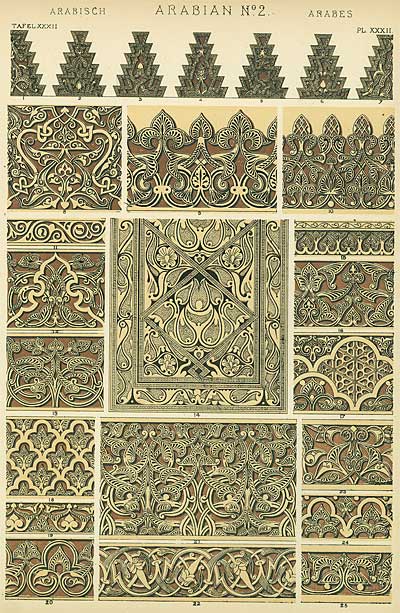

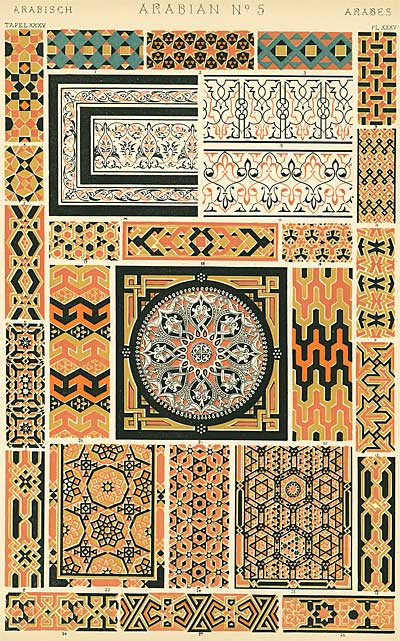

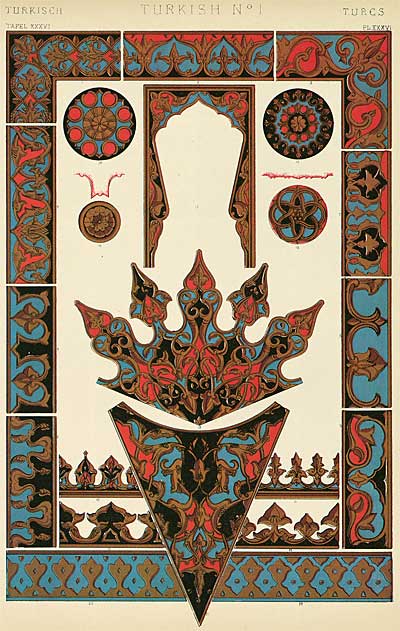

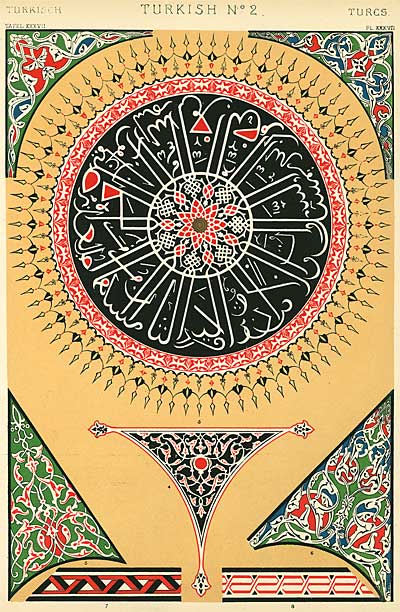

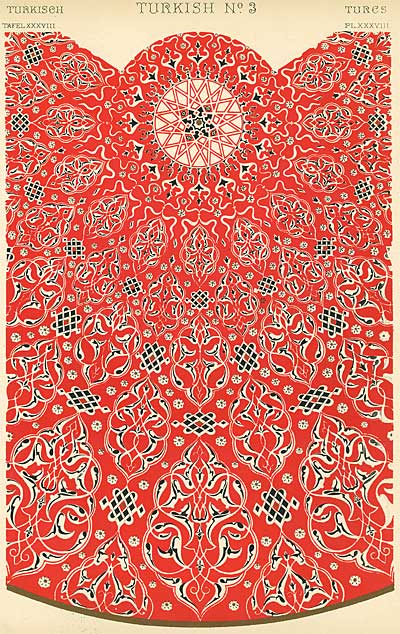

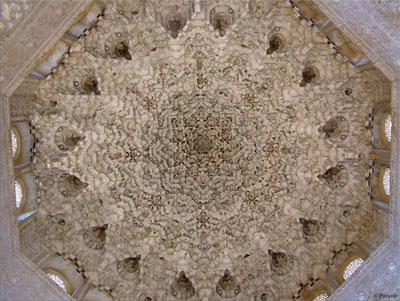

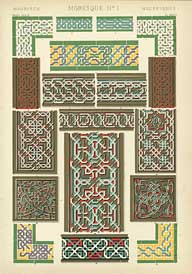

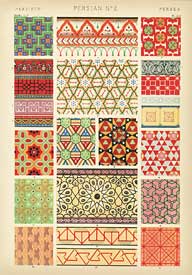

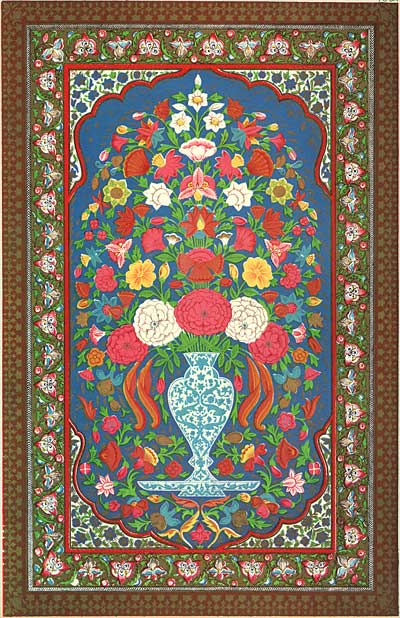

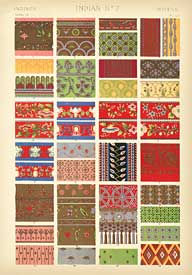

Curation is a similar process. Part of it is straightforward research. That’s the easy part. There are lots of librarians and historians who can catalog and document. It’s easy to look at the surface and say, “Disney made ‘Brave Little Tailor’ in 1938.” but that is just a statement of fact, not real understanding. The more difficult and intuitive part of research is discerning the connections between things that reveal the universal truth beneath. Yeah, I know… that sounds “hippy-dippy” and I apologize for that. But it’s the easiest way to describe it. The products of human creativity have cultural differences, and technique is dependent on technology. This makes them all look different. However once you dig beneath the surface, you start to see the invisible connections that make up the way humanity thinks, feels and creates. There are patterns that we all follow. If you want to be an artist, you may express those patterns and choices without even knowing it.

Connections: Tenggren, Dulac and Japanese Woodcut

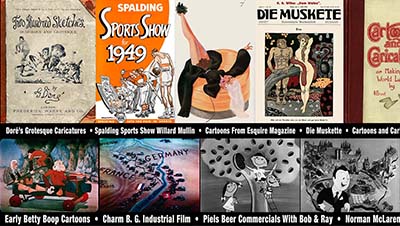

Lately, with COVID rapidly shrinking in the distance behind us, I’ve dived into several projects that are all linked, but the connections weren’t initially obvious. I’ve got a long list of projects on my “to-do list” that I haven’t gotten around to developing yet. One of those was investigating international animation. I read the Bendazzi book from cover to cover and it excited me about these films, but I had no way of accessing them. When a batch of Russian DVDs turned up on the greatest archive known to man— eBay— I jumped on it. It was a collection of over 75 DVDs of rare Russian animation. I started digitizing them and I was blown away at the diversity and quality of the work. Their approach to the art form is unique and pure. There’s so much to learn from these films! I’ve begun sharing the riches of the Eastern block in the Reference Packs.

Russian animation led me to thinking about the other great culture for animation— anime. I’m familiar with the usual suspects… “Akira”, “Kimba the White Lion”, the feature films by Miyazaki and others. But I never felt that Animation Resources needed to focus on that. It’s all readily available, and most animation students today know all about those films. But Animation Resources’ treasurer, JoJo Baptista showed me that there’s a lot more to Japanese animation than just the films we all know. Together, we started researching early Japanese animation. I discovered that before animation became standardized and institutionalized in Japan, there was a wide range of styles and ideas. I traced the history of animated features in Japan from the WWII propaganda film, “Momotaro’s Sea Eagles” through the 1960s, while JoJo focused on early television animation. He discovered some rarely seen series that are models of expressive economy. These TV programs addressed and solved the problem of how to keep limited animation lively- the same problem that independent internet animators face. We’ll be sharing that in upcoming Reference Packs as well.

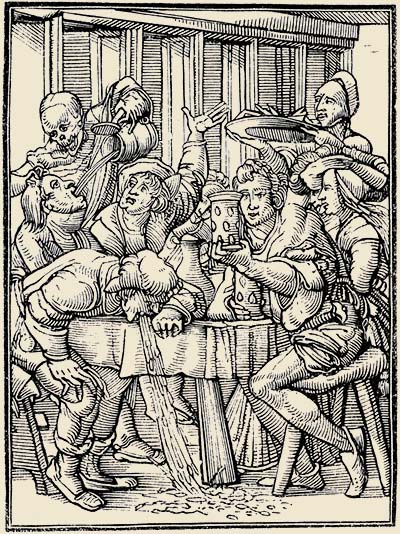

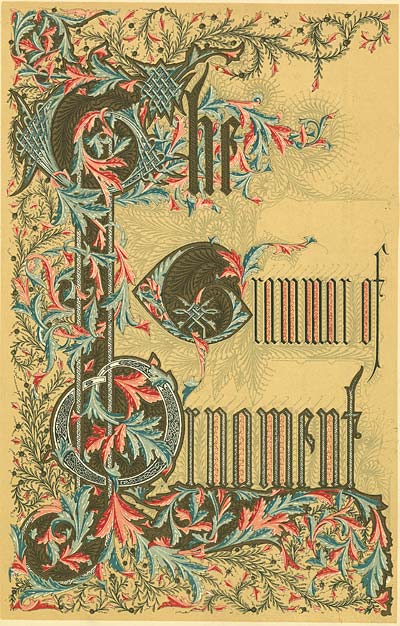

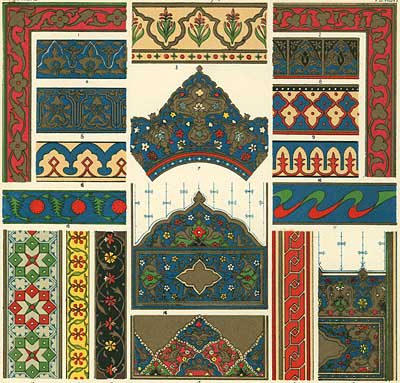

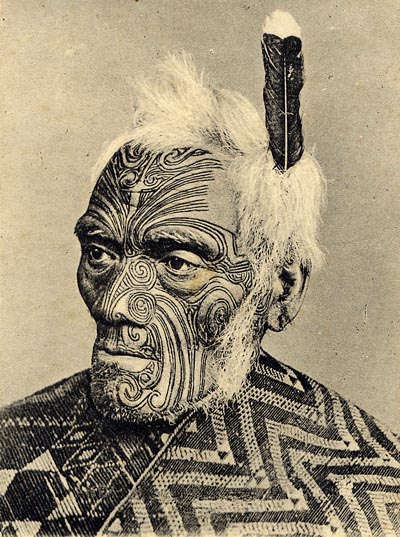

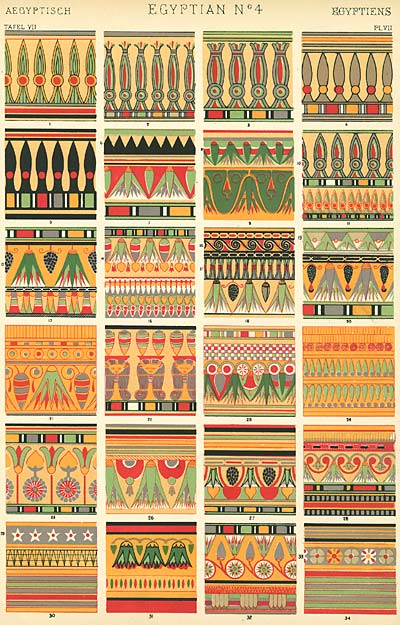

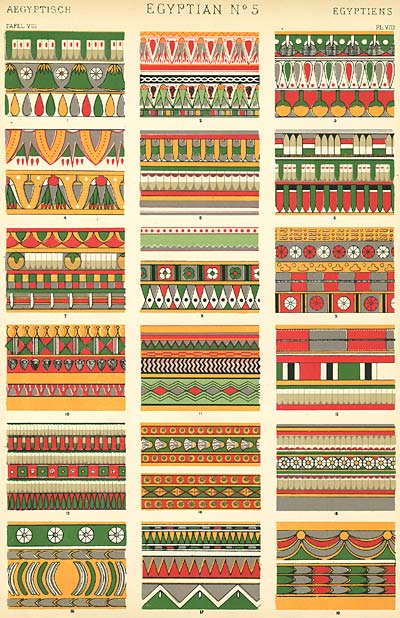

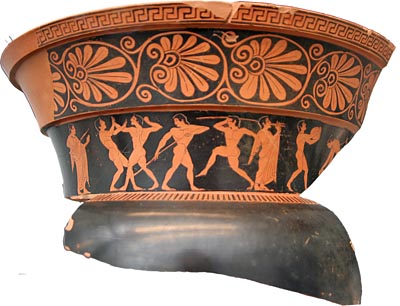

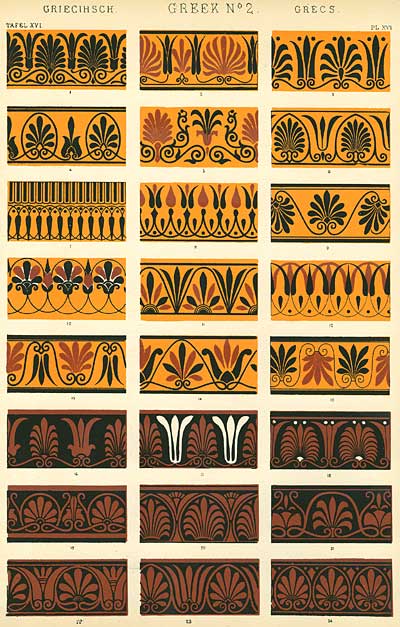

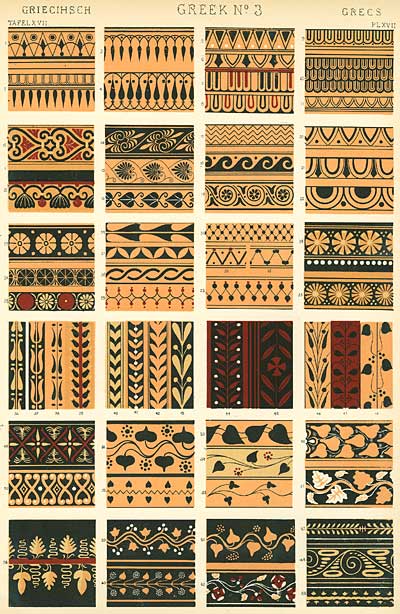

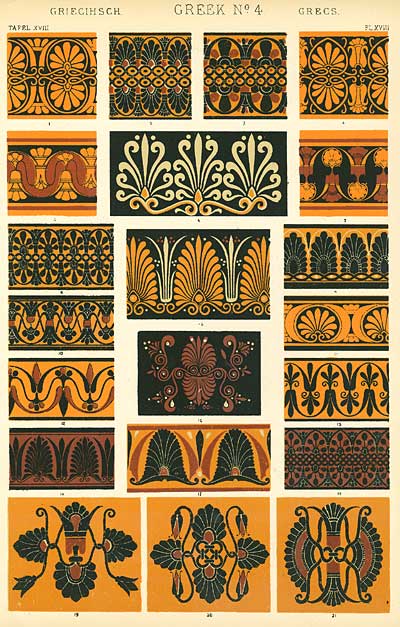

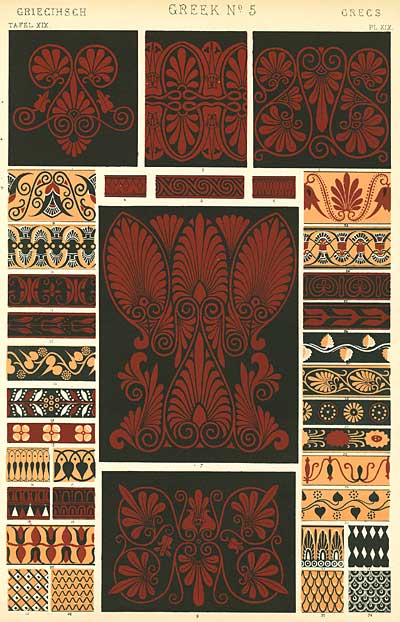

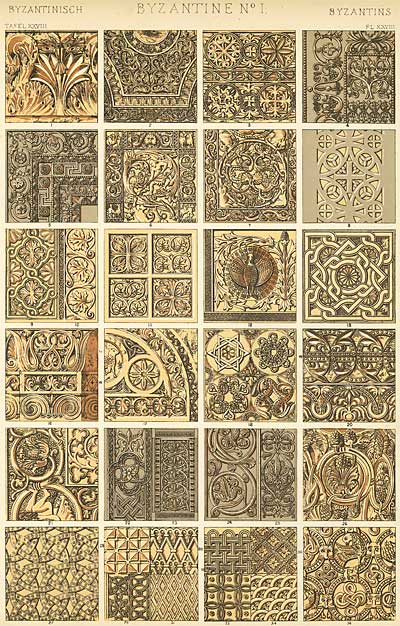

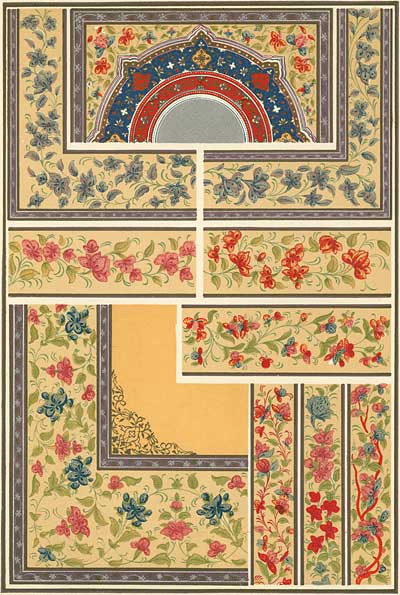

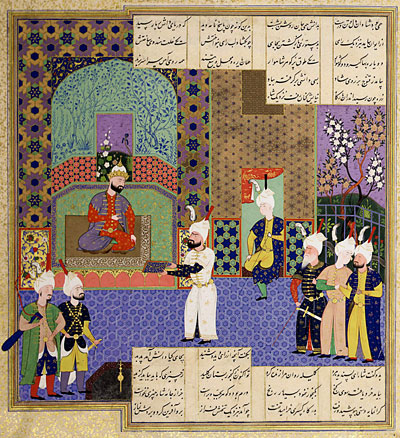

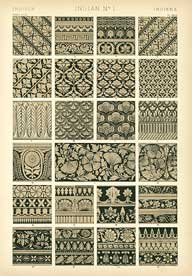

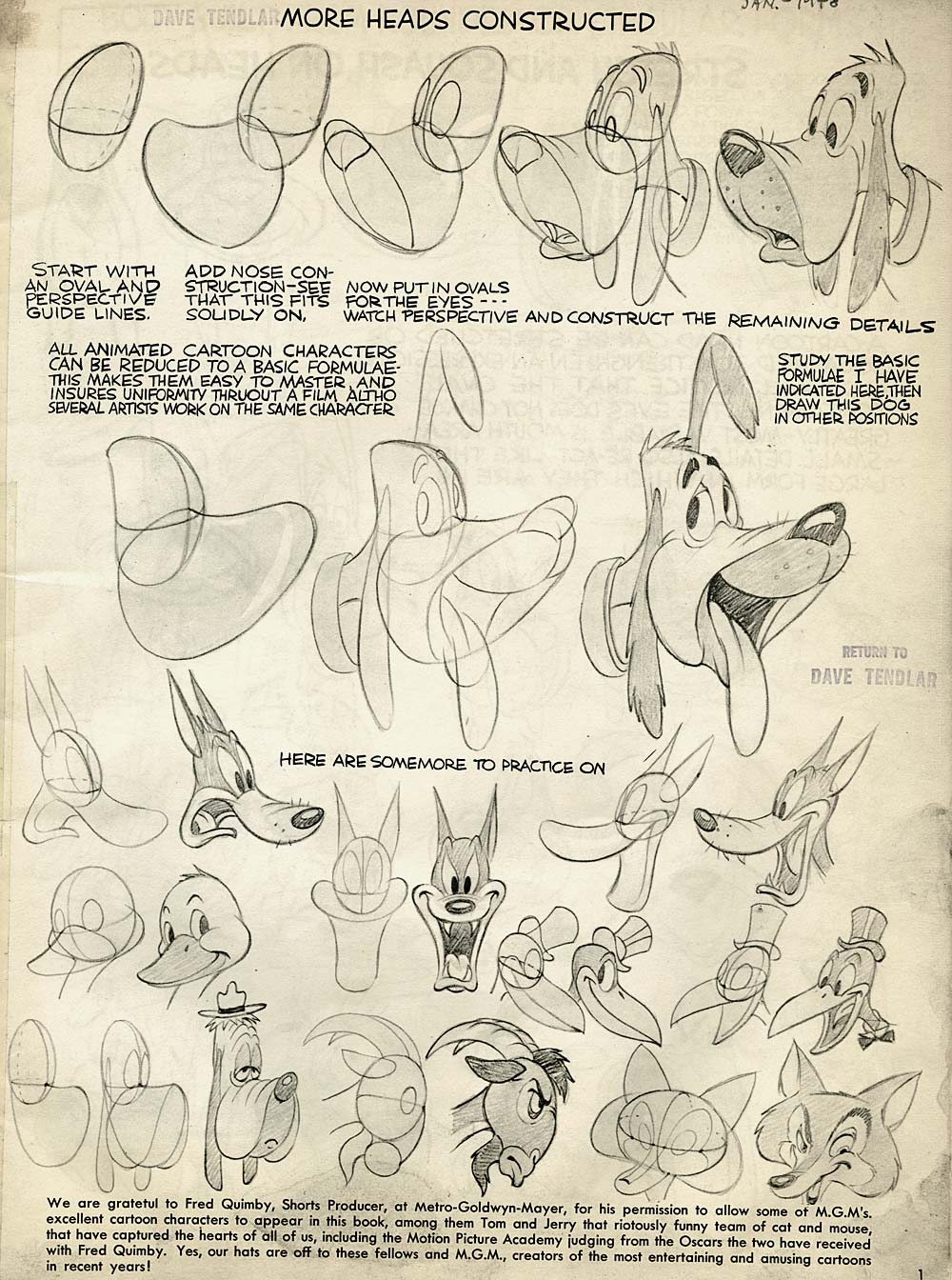

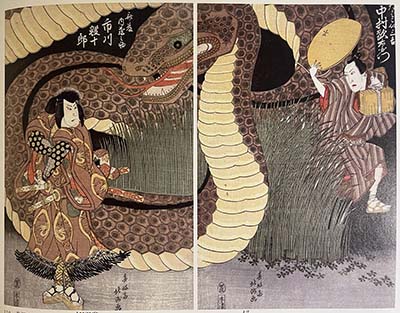

My research into the early history of Japanese animation led me down a rabbit hole similar to one I explored early on in the Animation Archive Project. Back in the mid 2000s I started tracing the lineage of Western cartooning backwards step by step, from the golden age cartoon films to newspaper comics to the earliest sequential cartoons to caricature magazines to British printmakers to woodblock carvers and ultimately all the way back to Leonardo daVinci’s grotesque caricatures. I learned that animation was just a part of the story. The history of Western cartooning is a continuum that extends back far beyond Winsor McCay. I discovered that on the other side of the globe, in near complete isolation, the same thing was happening in Japan. I’m now in the process of tracing anime back to manga to ukiyo-e and perhaps its earliest origins in Chinese painting. That research is just getting started.

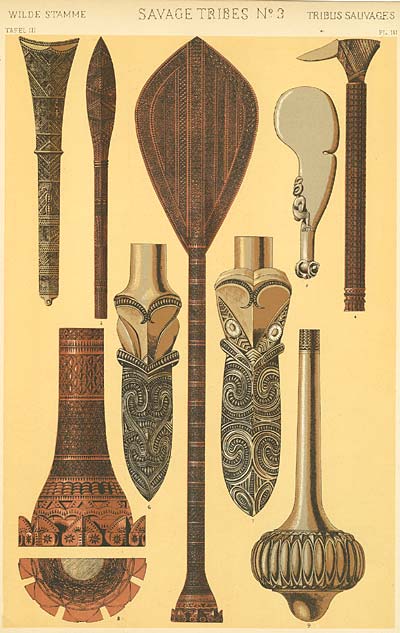

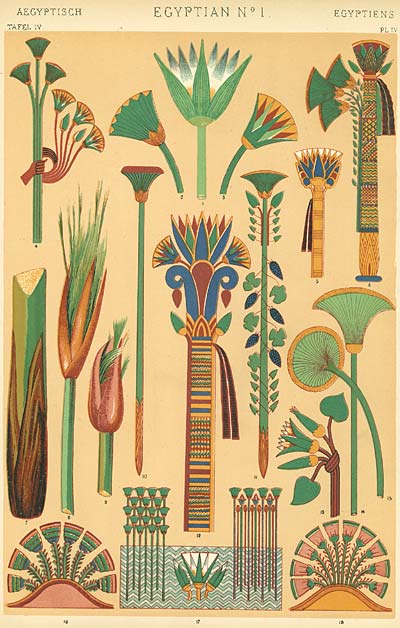

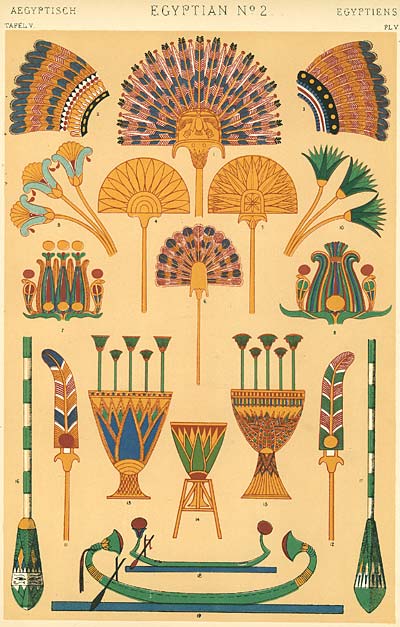

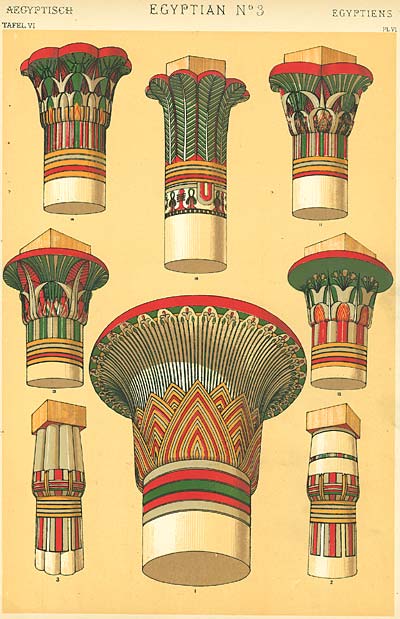

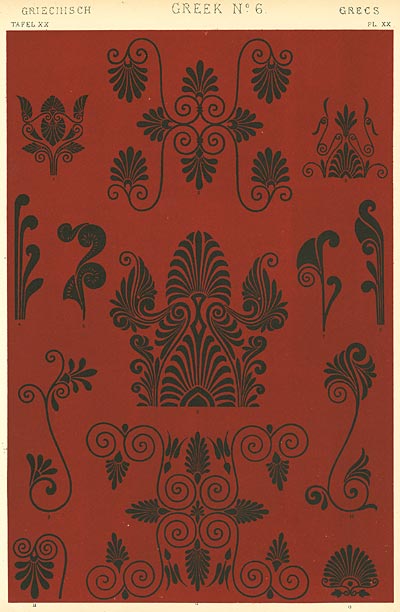

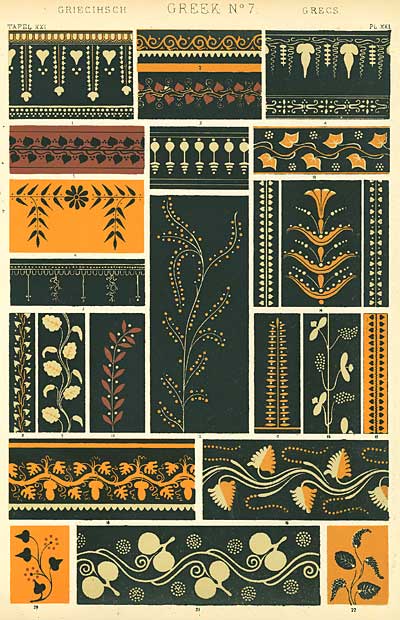

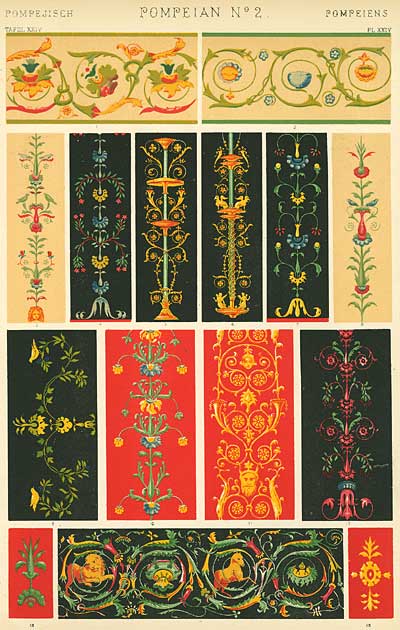

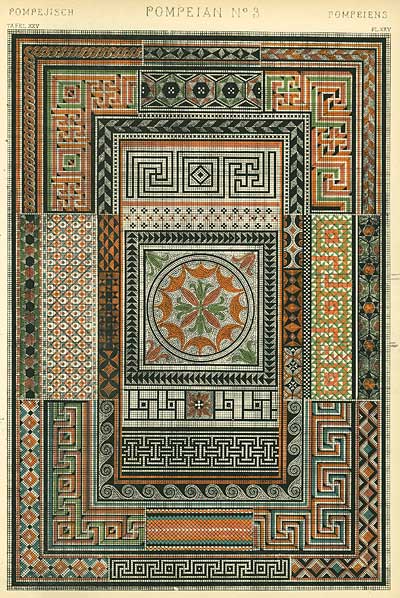

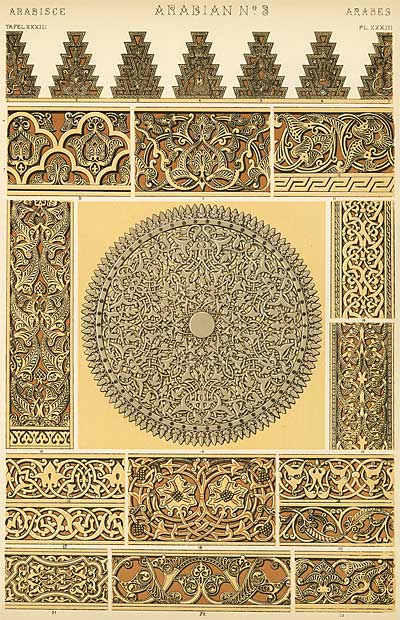

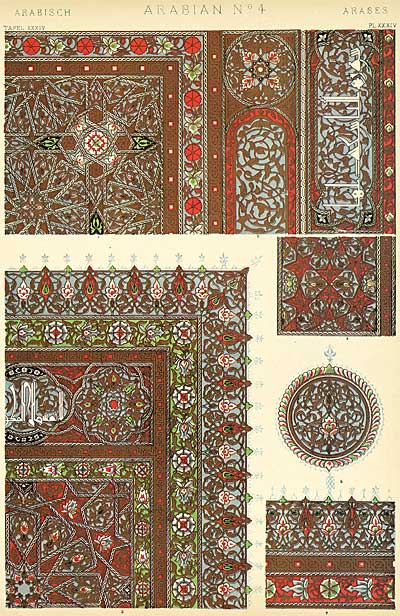

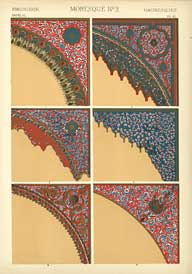

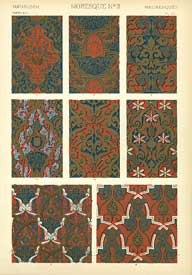

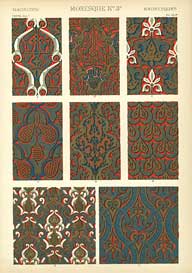

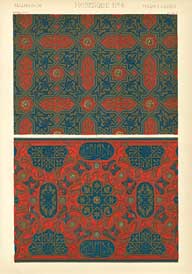

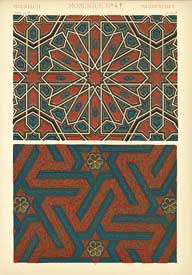

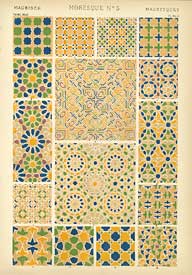

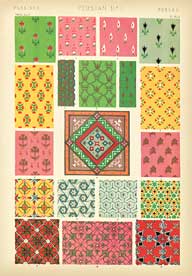

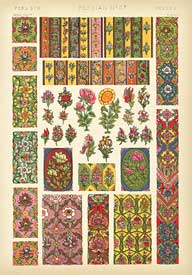

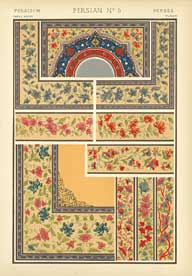

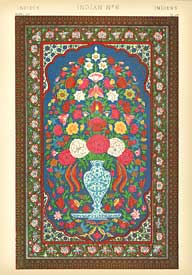

Those who have read my article on “Dances of Death” (included in the ebooks in our sample reference pack: https://animationresources.org/join-us-sample-reference-pack/) know the similarities I’ve found between late 15th century woodblock artists like Holbein and Durer and modern commercial cartooning. The EXACT same aspects are shared by Japanese woodcuts known as ukiyo-e or “The Floating World”. And the Japanese woodcuts led to manga, just as woodcuts led to comics. And you already know where comics and manga led!

This has been a very long post, and perhaps only a few have read this far. But Animation Resources has never been aimed at the typical followers of social media. 99% of the people who see and share our posts are just reacting to a pretty picture. That’s fine, but that isn’t why Animation Resources exists. Our real target audience is the small specialized number of creative artists who are actively analyzing and making the connections in their head to develop and hone their own creativity. If that describes you, I want to let you know that I’ll be sharing more about these projects in the near future. Keep your eyes peeled and your mind open. Come along on the journey with us.

If you aren’t a member of Animation Resources yet…

JOIN Animation Resources TODAY!

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

For the past decade, Animation Resources has been serving artists working in the fields of animation, cartooning and illustration. Our volunteers and members have pulled together to raise the bar for our art form, and it’s time to celebrate… It’s Members Appreciation time again!

During the month of February, Animation Resources expresses our appreciation for to members with a very special Reference Pack, and we invite you to become a member too. For the next 30 days, we will be sharing reasons why you should join us. Our benefits of membership far exceed the cost of our annual dues.

This year, we are trying something new to encourage new memberships. You can join for a one week trial membership for only A DOLLAR! Yes, you get access to everything our annual members get for seven days for only a buck. (Click here for the details on our Dollar Days.) What are you waiting for?

You can find out what our members get at the Member Appreciation Page. It’s easy to join. Just click on this link and you can sign up right now online…

JOIN TODAY!

https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

![]()

![]() Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.

Animation Resources depends on your contributions to support its projects. Even if you can’t afford to join our group right now, please click the button below to donate whatever you can afford using PayPal.